10 Things to Know About Alexander Calder

A closer look

•

26 Oct 2020

Alexander Calder, the inventor of the “mobile” and kinetic art… he was a master of gracefully balancing industrial materials with nature, making them work in perfect harmony. This major artist of the 20th-century changed the landscape of sculpture, introducing a new and delicate slant to this art form. Having worked beside Miro, Arman and Mondrian, today he is one of the most popular artists in the market. He is acclaimed by all the most highly regarded museums in the world and present in the most prestigious collections. Uncover 10 things to know about this artist who broke with conventions…

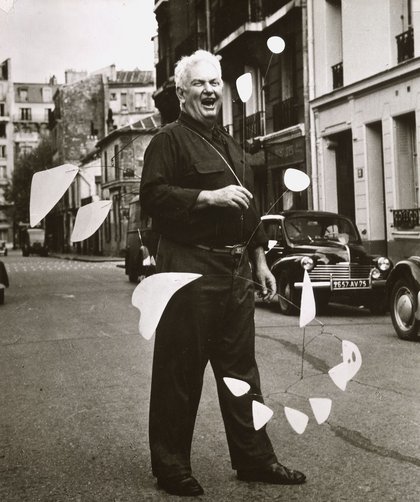

Agnès Varda, Calder with 21 feuilles blanches (1953), Paris, 1954

Agnès Varda, Calder with 21 feuilles blanches (1953), Paris, 1954

Mục lục

He was the pioneer of the mobile and kinetic art

Mobile, metal, wood, wire and string, 1932

Alexander Calder was the pioneer of the “mobile” that we know today, and the founder of kinetic art. The name “mobile” was gifted by Marcel Duchamp. This new structure broke with the conventions of sculpture in his contemporary setting. Calder’s sculptures were incredibly delicate and, crucially, they moved. Initially, Calder’s sculptures moved due to the use of motors. However, eventually they evolved to move due to natural forces. The sculptures were designed in such a way that they would catch the air currents in a room or the breeze outside, a revolutionary concept in the world of art. Hand in hand with the introduction of these “mobiles”, came the introduction of “stabiles”. This name was given by abstract artist, Jean Arp, to Calder’s previous stationary sculptures.

6

58542

He is known for ‘drawing in space’

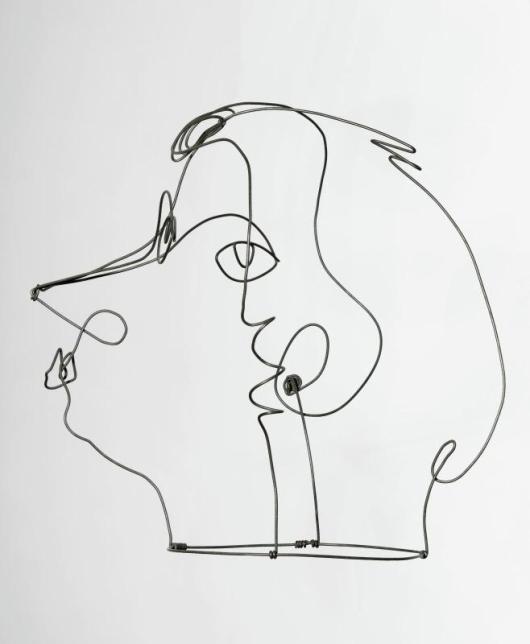

Kiki de Montparnasse (II), 1930, on display at the Centre Pompidou

The term ‘drawing in space’ was first used in reference to Calder in the French newspaper Paris-Midi. This came after one of his first solo exhibitions in 1929 in which Calder showcased his wire sculptures. The description stuck and was often used subsequently to describe Calder’s works. The term was also apt for Calder as he would carry bits of wire with him and fashion images of what he saw in the streets. Famously, he enjoyed creating wire portraits of people he met – one of his most well known was of the actress, Kiki, in 1929. Calder was particularly drawn to her nose which seemed to “launch off into space”.

He came from an artistic background

Photo credit: Thomas Powell Imaging, Dog (1909) and Duck (1909)

Coming from an artistic family, it is not hard to see how Calder ended up being such a pillar of the art world, although it was not his parents who pushed him into this career. His father, also called Alexander Calder, was a sculptor himself, so he knew the hardships that came with being an artist. He used to call his son ‘the garbage man’ as his pockets were always brimming with pebbles, string and odd bits and bobs.

From an early age Calder showed an interest in sculpture and using his hands to mold the world around him. At the age of 11, his sister bought him a pair of pliers for Christmas. He used these to make two little brass sculptures for his mother and father, one of a duck and another of a dog. Metal went on to be his principal medium. His work uses bits of old wire and wood, showcasing how beauty can be created out of unwanted scraps.

6

4456

He was a mechanical engineer turned sculptor

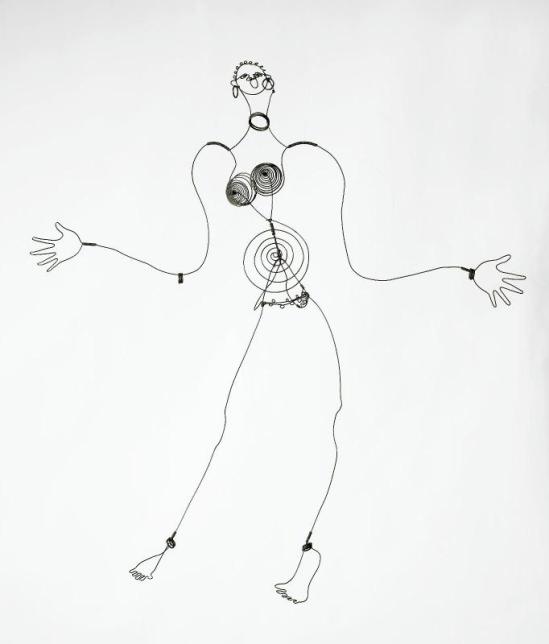

Photo credit: Georges Meguerditchian – Centre Pompidou, Joséphine Baker (IV), Danse, 1928

Calder studied mechanical engineering at Stevens Institute of Technology, graduating in 1921. However, whilst working on a ship in 1922, it was on seeing the red sun off the shore of Guatemala that he was reminded of his artistic upbringing. He turned his back on this lifestyle, initially moving to New York where he worked as an artist for several newspapers until he eventually moved to the art hub, Paris, in 1926. During his time in Paris he began sketching people in the streets and making little wire figurines in his hotel room. One of the first characters he made was Josephine Baker who was renowned across the globe for her Charleston dancing. It was this movement and energy that Calder tried to capture in his models of her.

Although his work never specifically relied on the knowledge he gained during his studies, it seems undeniable that his skills influenced his perfectly assembled sculptures. In fact, later in his career he stated: “When I work on something, I have two things in mind. The first is to make it more alive. The second is always to bear in mind the balance of it.”

He was always drawn to the circus

Calder’s Circus, 1926 – 1931, on display at the Witney Foundation of Arts

Calder sought to represent and capture movement in all his works throughout his lifetime. This fascination started whilst living in New York. For two weeks he visited the circus, a melting pot for the whole of society. Here he drew and painted the spectacles that he saw, trying to capture the animation of the environment. He would return to this inspiration throughout his career.

After moving to Paris, Calder created a miniature circus made out of wire and wooden blocks. It included characters such as a heavy weight lifter, a horseman and a clown. These were brought to life by Calder pulling different strings. His first performance was in his hotel room to some of his friends. One of these performances attracted Legrand-Chabrier, a renowned circus critic at the time. It was he who was the first to put Calder in the spotlight, writing an article about Calder’s humble but genius circus, titled; “Un Petit Cirque à Domicile”.

In 1929, Calder linked with Léonard Foujita, the Japanese-French painter and printmaker. Together they worked on Calder’s circus performances. Calder provided the circus and Foujita the music. These became increasingly popular and artists and intellectuals across Paris became interested. Visitors included the likes of Kiki, Marcel Duchamp, Jean Cocteau and Man Ray. The circus became so popular that by the beginning of the 30s it had grown from 15 to 200 figurines.

He was inspired by meeting Mondrian

Untitled abstract painting, 1930 after meeting Piet Mondrian

In 1930 Calder was invited to Piet Mondrian’s studio in Paris. Here Calder was inspired by the colorful squares dotted over the white walls of the studio. With this image, complemented by the light streaming into the space, Calder suggested to Mondrian that he set the squares into motion. To this Mondrian responded: ‘No it is not necessary, my painting is already very fast…’. Nevertheless, this encounter inspired Calder to pursue movement with even more vigour.

After meeting Mondrian and encountering abstract art for the first time, Calder locked himself away painting simple canvases that aligned with this idea. However, he quickly grew tired from this medium. But, having been exposed to simple shapes and arcs, he began to view figurative representation as limiting. In his next exhibition Volumes, Vectors, Densities at the Galerie Percier, he presented sculptures made from different elements of a circle. Following on from this exhibition, Calder came to be regarded as a serious contender in the world of abstract art.

6

6785

The War Years altered the materials he used for his sculptures

Constellation Mobile, made from wood, wire, string, paint, 1943

The War Years brought with them a shortage of sheet metal. This posed a problem for Calder who relied on this material to create his masterpieces. Usually he would cut sheet metal into pieces that he would then assemble into his mobiles. However, this did not phase Calder. Instead the shortage brought with it a new era for Calder who turned to more natural materials. Wood and wire became his new tools. With this new medium, Calder created his Constellations series in the 1940s, so called because the sculptures resembled the Cosmos.

He has had multiple giant structures displayed across the globe

“L’Homme” (The Man), Montreal, 1967

Later in his career Calder was often commissioned to create giant structures. For example, The Red Spider (1976) and Spiral (1958) in Paris, and Flamingo (1974) in Chicago. In order to create these structures he would first make models of them, then they would come to fruition in one of his studios. One of the largest of these sculptures was Man (1967) which was installed in Montreal and stood at 65 feet. These monumental sculptures could be found in cities and the countryside alike and are the principal examples of Calder’s “stabiles”.

He once collaborated with an airline

Collaboration with Braniff International Airways, 1973

In 1973, Calder was commissioned to design the outside of an aeroplane in his typical bright style by Braniff International Airways. This project came to be known as Flying Colours, primarily flying to South America. The outside of the plane, instead of having the airline’s logo, had Calder’s signature on the outside. In 1975, he was commissioned to decorate another plane, which came to be known as Flying Colours of the United States.

He never wanted to be defined by a particular artistic movement

Steel Fish, 1934, the first of Calder’s sculptures to be exposed to the elements

Although mingling with the abstract artists of the day, Calder never sought to be defined by a particular artistic movement. In fact he was specifically anti this concept. He was of the opinion that when an artist defined themselves, this was when they became limited. Instead he believed that when an artist was attempting to explain their work, they should in fact be challenging their ideas. About his own work, Steel Fish (1934), he stated: ‘this is completely useless and meaningless. It’s just beautiful, that is all. It can make you very emotional if you understand it, of course, if it had some meaning it would be easier to understand’.

To conclude, Alexander Calder truly underwent an evolution throughout his career. From his original wire portraits to his monumental sculptures, Calder’s creations were the result of true artist exploration. He drew on inspiration from everyone and everything he encountered throughout his life. However, he managed to maintain his true to his values and beliefs throughout his life, allowing him to create truly forward thinking sculptures. Ultimately, these qualities meant he completely transformed sculpture as we knew it into a lighter and more playful art form.

6

3003