100 Designs That Encapsulate the Power of Chanel

Distilling more than 100 years of fashion from the house of Chanel down to its essence in a mere 100 designs seems an impossible task. Yet Chanel: The Impossible Collection does just that, thanks to the astute eye of its author, well-known fashion journalist, critic and collector Alexander Fury. The latest publication in Assouline’s limited-edition Luxury Collection is a sublime visual narrative that walks us through Chanel’s evolution so that, in the words of CEO Martine Assouline’s foreword, we “understand how unique and timeless a name can be, even beyond its glorious creators.” Assouline is actually referring to just two people, whose tenures are unmatched in the business of fashion: the brand’s eponymous founder, Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel, and its rightful heir and artistic director of 36 years, Karl Lagerfeld. As Fury succinctly asserts in his introduction, brand Chanel is colossal.

As is Chanel: The Impossible Collection. Weighing in at 21 pounds, it practically deserves a lectern, not a coffee table. And like the leather-bound illustrated medieval Bibles often read from lecterns, this contemporary tome is hand-crafted. Each of the 100 looks, which are split between Coco and Karl, is given a full-page color visual, and the book itself is encased in a black linen clamshell case. On the cover is Man Ray‘s 1936 iconic monochrome photograph of a rakish Coco in haughty profile, cigarette in mouth — a modern woman dripping with pearls, cuffed, a feminist fatale. According to Fury, this is the first book to unpack the meaning of Chanel through the fashion.

“Many may assume Chanel’s history to be static, knowing well the symbols, emblems, icons of its unmistakable style,” Fury writes in the book. “Yet fixed though the idea is, ‘le style Chanel’ has actually always existed in a state of constant reinvention, always moving with the times.” To understand “le style Chanel,” Lagerfeld said, just look and you will get the message. To that end, Fury and Martine Assouline have sourced an array of important fashion images from such institutions as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and private collectors like Daphne Guinness. There are also illustrations by Cecil Beaton, Christian Bérard and Lagerfeld, plus archival prints of Chanel’s friends, including Count Fulco di Verdura and Ballets Russes principal Serge Lifar, which are interspersed with iconic photographs by greats like Helmut Newton, Peter Lindbergh and André Kertész.

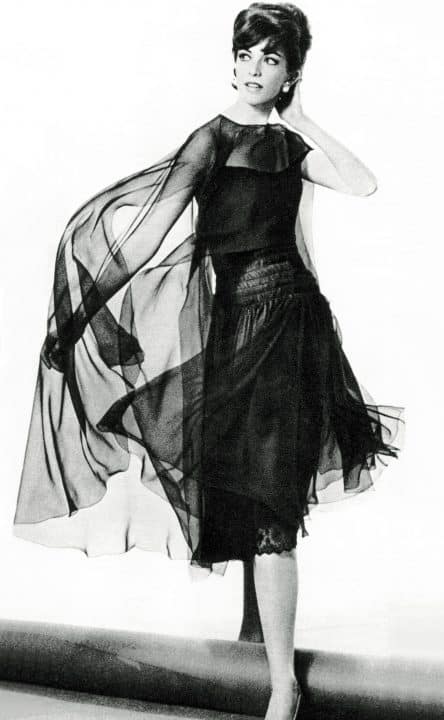

“I really wanted to include archival lifestyle photographs because Chanel’s radical style really came from the clothes she wore, how she lived, very much like Le Corbusier and his architecture as a tool for life,” Fury says, sitting back in his chair with a challenging grin. The author, chatting with Introspective in London, is referring to Le Corbusier’s 1927 manifesto, Towards a New Architecture, in which he states that buildings should be well-engineered streamlined structures designed with comfortable furnishings. Leaning in, Fury continues, “It’s incredible to think she was designing simple, practical clothing when fashionable women were contorted in highly decorated gowns.” Her fluid fabrics liberated the female form to enjoy the freedoms that burst upon the cultural scene following the austerity of World War I, with gamine girls, their cropped hair, hiking up their hemlines and kicking up their feet to a newfangled beat called jazz.

Absence of vulgarity was central to Chanel’s definition of luxury, a view formed during her impoverished early life. Born in 1883 in Saumur, France, as Gabrielle Bonheur Chanel, she was just 12 years old when her mother died and her itinerant father put her in a home for orphaned girls run by a local convent. She learned to sew and, upon moving to Moulins six years later, became a seamstress. She also sang in nightclubs, earning the sobriquet “Coco,” an allusion to a popular song of the time.

In 1913, she opened her first boutique, in Deauville, financed by Englishman “Boy” Capel, one of her many wealthy lovers. Already, she was developing “le style Chanel,” an insouciant pragmatism that was a hybrid of previous deprivation — the black of nuns’ habits became her little black dress — and her current life of aristocratic luxury. In a 1937 photograph, Chanel sits on Lifar’s shoulders, both wearing identical clothing, androgynous, she with strands of pearls. In addition to those now-signature pearls, Chanel: The Impossible Collection illustrates iconic examples of her fashion-forward, pared-back designs, including her interpretations of menswear: pleated pants and evening pajamas, jersey knits and fine tweeds, with such feminine touches as bias silk and delicate lace. “She was a maverick, you know,” Fury says. “I think she really enjoyed going against norms. She did her first fine jewelry collection using diamonds during the Depression!”

Halfway through the book, we meet Karl Lagerfeld. Born into a middle-class family in Hamburg, Germany, Lagerfeld had worked in Paris since 1955 for such luminaries as Jean Patou and Pierre Balmain, as well as on his own eponymous line, when, at 50, he was hired to reinvigorate a moribund Chanel in 1983. The book shows one sorry suit from before his appointment, and it’s all we need to get the message that he was a godsend. We see Coco’s iconic motifs given new life in Lagerfeld’s deft hands. Her signature ease becomes his signature tease, as her female softness evolves into a masculine angularity that reflects the empowering ’80s.

Fury sees this difference as a difference in design, not just estrogen versus testosterone or one era versus another. “Chanel designed on the form,” he explains. “She couldn’t draw, whereas Lagerfeld was visual and sketched every look before handing it to the atelier. He even reviewed its progress by looking at pictures. She was three-D, he two-D.” This is exemplified by his 1986 suit, shown on model Inès de la Fressange, which appears to have been created in a flat plane. Using Coco’s quilted leather bag as inspiration, he created a quilted suit that riffs as well on her elegant postwar signature suits. The fabric is taut with embroidered black sequins, the jacket boxy. The silhouette is angular, aggressive. Lagerfeld visualized the modern, independent woman as one who rode motorbikes, went scuba diving and wore denim and T-shirts and leather.

Lagerfeld invented the role of artistic director at Chanel through a prodigious capacity and talent for timely reinvention. “I’m like a computer who’s plugged into the Chanel mode,” he told WWD in 1983.

“You know, Karl’s death in February really impacted the book,” Fury says. “It was about to go to print, but then, putting in a dress from what turned out to be his last collection was really important. I chose one that references nineteen-thirties Chanel, romantic and feminine. He was born in nineteen thirty-three, and it was one of his favorite periods. He went back to his own beginning, yet it also acts as a full stop, an end.” Indeed, each of the 100 designs in Chanel: The Impossible Collection bears witness to a glorious history buttressed by two colossi of fashion. Coco Chanel stands at the source, Karl Lagerfeld at the mouth, and between them flows “le style Chanel.” If we hadn’t seen it, we wouldn’t have believed it was possible.

Shop Chanel on 1stdibs

Buy the Book