A History of Calvin Klein’s Biggest & Wildest Moments

How do you even begin to understand a powerhouse like Calvin Klein? Over half a century, the brand has tested and transformed global visual culture through experiments in fashion, media, and product design. Like the New York City skyline, it reflects the libidinal, aspirational and optimistic force of America, streamlined into bold gestures in black, white, and grey.

The following A-Z is a time machine stopping off at some of Calvin Klein’s most memorable product and controversial ad campaigns, visiting the numerous minds and muses associated with it.

Some designers and some artists seem able to ride the wave of history. Calvin Klein is one of them.

Speak the words Calvin Klein out loud and visions of bodies, as much as clothes, spring to mind. Over the last five decades, the brand’s vision of the zeitgeist would reshape and restructure America’s self-image, transmitting secrets from the heart – or abs – of the nation’s psyche. Along the way, Klein enlisted photographers, stylists, models, writers and designers that enabled him to tap into the present, rejecting European dominance in fashion by making his sporty, minimalist garments the stage for a new and raw vision of sexuality.

To view this external content, please click here.

Creating an image was critical to communicating my work to the world. I had a special relationship with every photographer I worked with. There was a constant conversation about my personal feelings for this woman and how the photographers would interpret her. Bruce Weber and I shared an extraordinary bond, which spanned more than fifteen years and produced some of our most iconic images. Patrick Demarchelier, Peter Lindbergh, Mario Sorrenti, David Sims, Steven Klein, and Craig McDean – each brought a new perspective to my work

Calvin Klein, Calvin Klein by Rizzoli

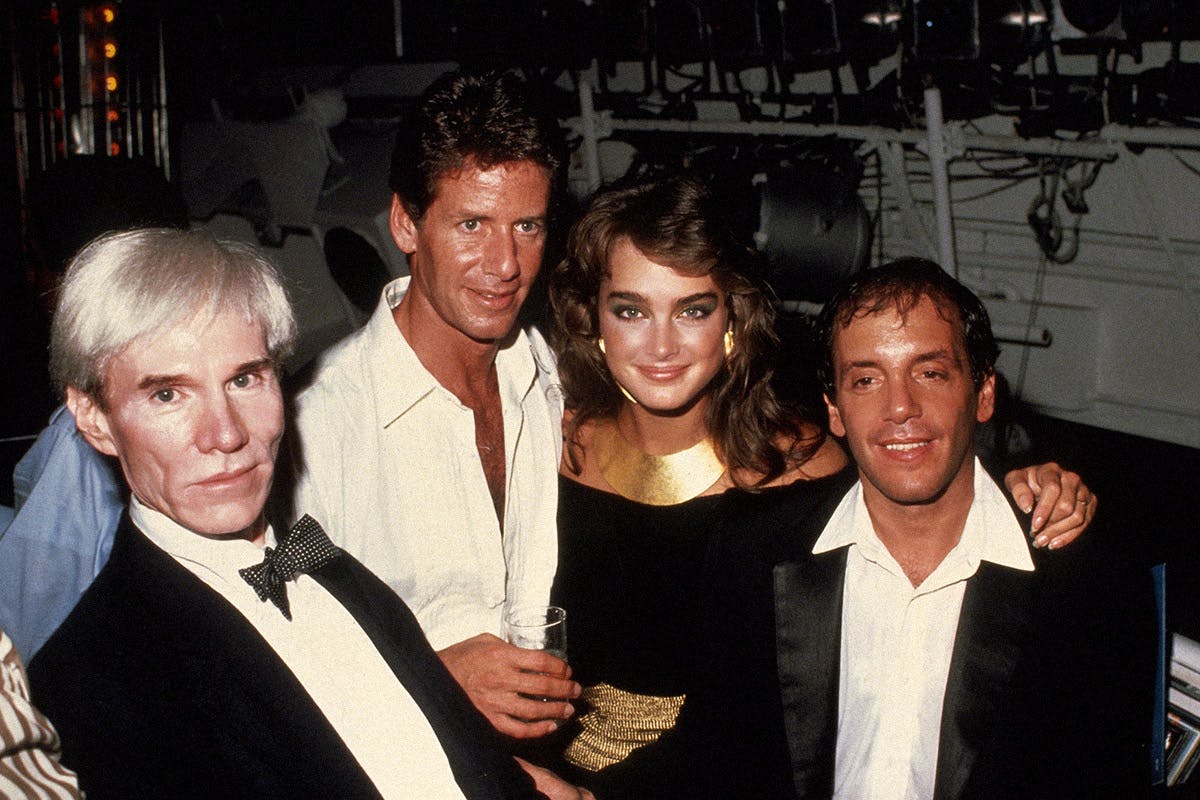

Calvin Klein, founded in 1968, enjoyed critical success in the ’70s, but the brand’s visibility went nuclear in 1980 when Klein asked photographer Richard Avedon to shoot a series of commercials featuring a 15-year-old actress and model named Brooke Shields. In the series’ best-known spot, Shields crouches awkwardly – legs splayed in a compromising yoga-like pose. The camera ascends slowly until she looks up and whispers the now-immortal line: “Want to know what comes between me and my Calvins? Nothing.”

Shields had played an underage sex worker in French director Louis Malle’s film Pretty Baby, which may have partly fueled the outrage that led to TV networks ABC, NBC, and CBS pulling the ad.

Nonetheless, the series represents a milestone in controversy marketing and led to boosted sales. “Jeans are sex,” Klein declared, unremorseful, as his personal income passed $8.5 million per year (according to Forbes). “The tighter they are, the better they sell.”

Calvin Richard Klein was born November 19, 1942, and raised in the Bronx by father Leo, a grocer and Jewish immigrant from Hungary, and mother Flore (née Stern), a fashion-obsessive from whom he absorbed his early aesthetic direction.

“I spent the first ten years of my life designing beige, cream, white, brown, because those were all the colors that [my mother] loved,” said Klein. “She would line her jackets in fur, she would do all of these outrageous things considering that we came from what you would call a very middle-class family in the Bronx.”

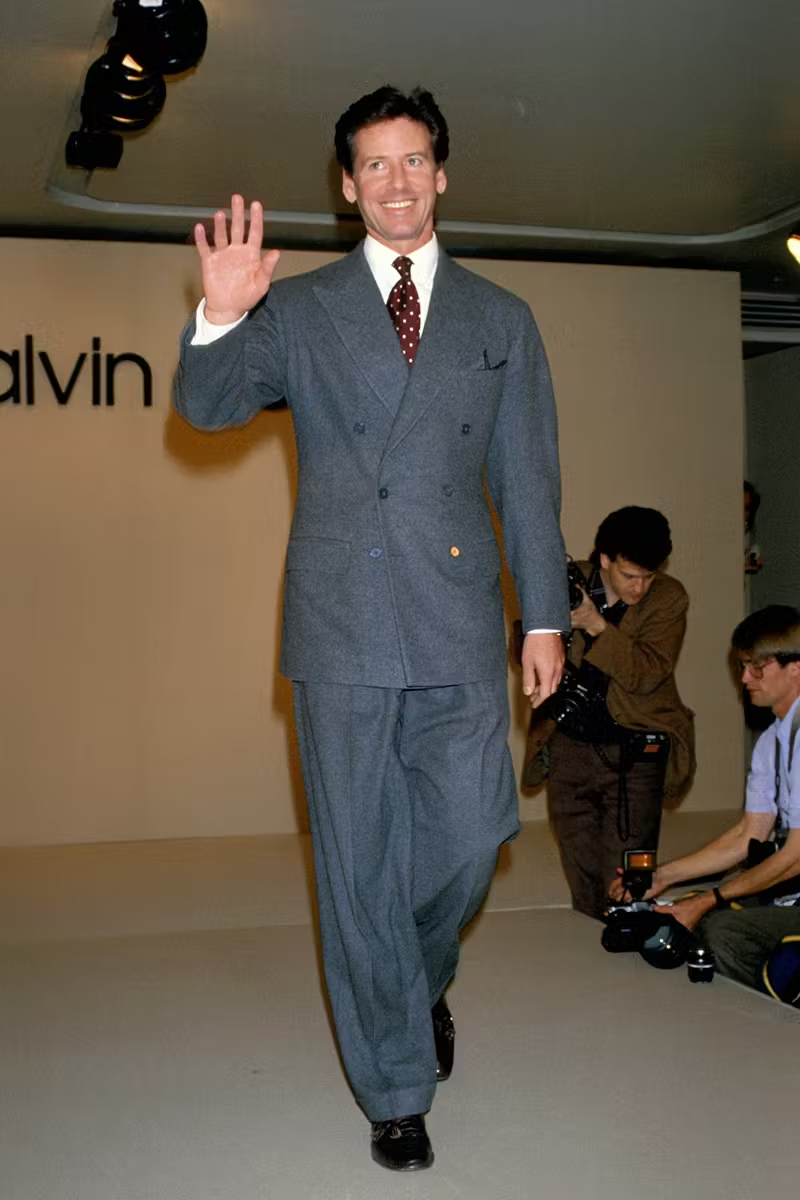

Getty Images / PL Gould

After learning to sketch and alter garments in his grandmother Molly’s dress shop, Klein proceeded through Manhattan’s High School of Industrial Arts and Fashion Institute of Technology, from which he graduated into a succession of boring design jobs. It was his childhood friend since age five, Barry Schwartz, who supplied the cash to fund his first line, a series of six neatly-cut “architectural” coats and three dresses that Klein famously wheeled across town on a clothes rack to an appointment at luxury boutique Bonwit Teller, hoping they wouldn’t suffer a single crease. It was 1968. Klein left Bonwit Teller with a $50,000 order to fulfill. The following year, in 1969, his designs appeared on the front cover of Vogue.

[Calvin Klein] is down to earth, direct, and has an easy sense of intimacy. He also has a seductive boyishness that has nothing to do with age, not to mention good looks, cool, and a magnetism that attracts both sexes. (When I was interviewing people about him for this piece, I was struck by how many men and women confessed that they once had a crush on him.) None of this hurts when you’re trying to make your way in the world, especially if you also have promise, which Klein did, winning him the support of an established designer, Chester Weinberg, and the editors who ruled the fashion press.

Ingrid Sischy, Vanity Fair

Calvin Klein sold 200,000 pairs of denim jeans during its first week of sale in 1978 – a venture that arose after a stranger approached Klein on the dance floor at New York City’s most infamous party spot, Studio 54.

Studio 54 first opened in 1977 and became a fairground of disco, gossip, and amphetamine-powered excess. Around that time Vogue speculated, “If you were around a hundred years from now and wanted a definitive picture of the American look in 1975, you’d study Calvin Klein.” The designer had become a celebrity who embodied. It was to be expected that he would join Andy Warhol, Grace Jones, Bianca Jagger and Liza Minelli at Manhattan’s most exclusive club.

One night, shortly before dawn, a figure approached Klein and asked if he’d like to make a million dollars. He wanted to apply Calvin Klein’s name to jeans produced by manufacturer Puritan Fashions – a monogram would sit at the waist just above the butt. Puritan Fashions would later be subsumed within Klein’s business for a neat $68 million in 1984, by which point Klein was shifting $500 million worth of denim per year.

CK One, the citrusy fragrance developed by Spanish perfumer Alberto Morillas and launched in 1994, was the first unisex scent to gain popularity in the U.S. The marketing around it was similarly pioneering, integrating technology to appeal directly to the hormonal teens who were its target demographic.

In 1998, advertising agency Wieden + Kennedy directed a team of contracted fiction writers to staff mailing lists attached to email addresses – [email protected], [email protected], and [email protected] – printed next to models in their ads. When someone contacted the address, they would get back a personalized letter in return.

This is the sort of early digital and interactive marketing that would inform projects like “singer” Lil Miquela (seen kissing Bella Hadid in a Calvin Klein ad from May this year) or the high school Scandi drama, Skam. As the seasons rolled over the brand ditched the ads but continued paying writers to communicate with fans for another two years.

In 1992, Frenchman Fabien Baron commenced a 20-year stint as part of Calvin Klein’s creative team, steering the brand through some of its most iconic campaigns, namely the glitchy, Y2K-themed broadcast from 2011 in which Lara Stone stoops towards a distorting TV screen, suggestively and spelling out the word “F**K.”

There’s a roll-call of unforgettable campaigns on Baron’s website, but possibly his biggest contribution was more material than media. In 1994, he oversaw the product design for perfume CK One, described by New York Times fashion critic Eric Wilson as “arguably the most perfectly tailored fragrance ever pitched to one market, breaking industry rules and records, selling twenty bottles per minute at its peak.”

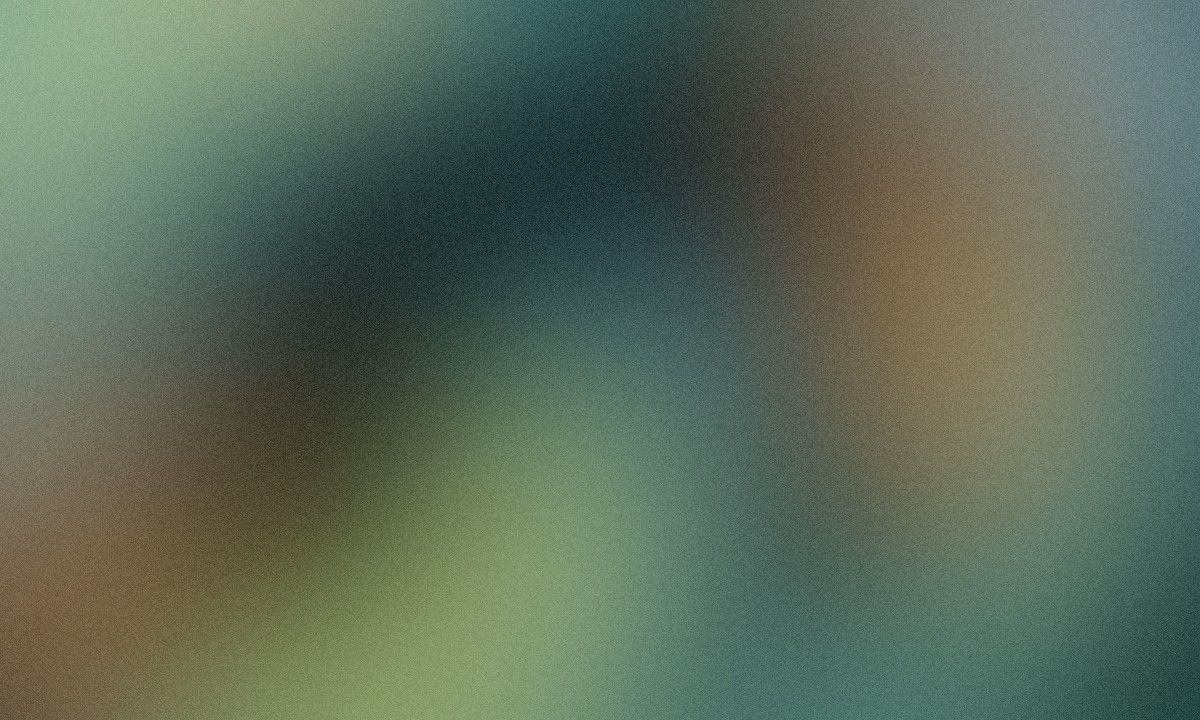

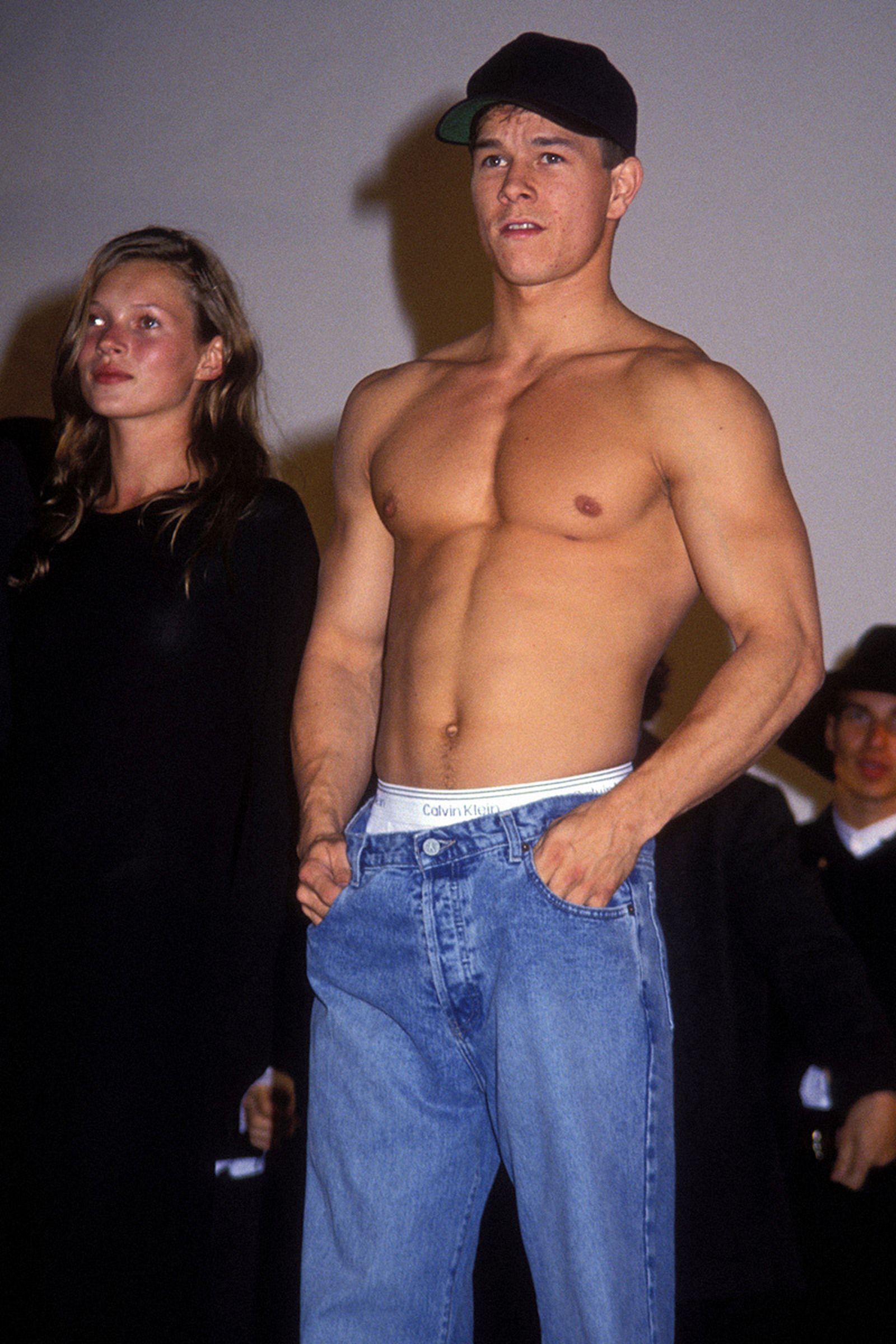

Calvin Klein prides himself on finding the ideal face and body to best fit the moods and desires of the present, even if they might make ostensibly odd bedfellows (think back to the 1990s, when he paired British model Kate Moss with Mark “Marky Mark” Wahlberg).

When it comes to pushing scents, the choice of model is critical because there’s no visible product – the personality represents an idea. That hasn’t stopped Klein from toying with boundaries, however, like in 2008 when Eva Mendes’ nude ad campaign for Secret Obsession was banned in the U.S.

To view this external content, please click here.

Before this, in the late 1980s, it was Christy Turlington – usually on a beach, later with husband Ed Burns, occasionally with a child – who was selected as an antidote to the nihilism of the times. “I always felt her intelligence came through in photographs,” Klein said.

The arrival of the #mycalvins campaign in 2014, seeded by influencers and emulated en masse, was a masterwork in the science of UGC (user-generated content). There are now 762,794 posts using the #mycalvins hashtag on Instagram, mainly athletic would-be brand ambassadors flexing in clothes they paid for, doing their best Justin Bieber impersonation.

According to WWD, the #mycalvins campaign reached a global audience of more than 469 million and led to more than 23.5 million fan interactions. The brand is active on Tinder, Snapchat and TikTok, and has run augmented reality ads. In 2015, it ran chat logs – “raw texts, real stories” – from Grindr and Tinder that were “inspired by actual events and people.”

By the early 1990s, the potency of Calvin Klein’s visual identity was so all-consuming it became an easy reference point for both pop culture and upstart brands hoping to make their mark.

Shortly after opening in April 1994, a wave of Supreme box logo stickers started appearing slapped across a monochrome Kate Moss, casting the brand name in sharp relief. Later that year, Calvin Klein filed a lawsuit against Supreme accusing them of defacing their advertising, a failed attempt that saw the mega-brand contend with the methodology of streetwear.

Artist KAWS similarly “disrupted” an ad featuring Christy Turlington in 1997 by painting one of his Companion characters behind the model. That particular work sold as “Untitled (Calvin Klein), Christy Turlington Ad Disruption” in a Tokyo auction last year for ¥14,375,000 (around $127,000).

When it was announced that Calvin Klein would close its flagship Collections store on Madison Avenue in January this year, Architectural Digest reached out to English architectural designer John Pawson, the man behind the design, to reflect on the 25-year life of the groundbreaking, minimalist space. “Imagine getting a call out of the blue,” Pawson said. “I’d just been out for lunch, I got back and the office said, ‘Oh, Calvin Klein’s been on the phone. I thought it was a joke. This was 1993, it was a young practice, we’d never done anything big, and, of course, he was such an iconic name. It turned out he was in the car outside.”

Getty Images / Maiman/Sygma

Pawson transformed the 22,000 square-foot space, formally a neoclassical bank, by installing glass frontage that ascended from street-level to the third floor, winnowing away walls and columns to create maximum space in which to present a relatively small number of clothes. “The things that I applied to that store,” Pawson told AD, referencing other notable projects including a monastery in the Czech Republic and the Cathay Pacific lounge in Hong Kong, “are really just trying to make sure people feel comfortable, whether it’s shoppers or monks.”

In “The Pez Dispenser,” episode 14 in season 3 of Seinfeld, Jerry’s neighbor Kramer pitches an “invigorating” scent he calls “The Beach,” designed to make the wearer smell as though freshly returned from a day of sun and surf. Although initially rejected by Calvin Klein marketing department suit Steve D’Giff, the lightning bolt idea returns in “The Pick” the following season, where Jerry’s date Tia Van Camp (played by Baywatch actor Jennifer Campbell) stars in a magazine campaign for CK’s latest fragrance, “Ocean by Calvin Klein.”

When Kramer heads to Trump Tower to confront Calvin (played by Nicholas Hormann), the designer, with trademark black polo neck and abundant grey hair, notices Kramer’s “interesting face” and “lean but muscular” physique, landing him a gig as an underwear model. “You’ve done it again, C.K.” one executive applauds.

Futura. Serif. An art deco flourish that screams Manhattan in its stem and stroke. Upper-case. Lower-case. Black. White. Grey. These are the raw materials that saw Calvin Klein pioneer robust, typographic design decades before it was cool.

The first iteration of the logo we recognize today emerged in the ’70s, created by Welsh designer Jeff Banks. A small “c” nestling up against a large “K” with the full name in Futura font underneath appeared ostentatiously on the rear of the brand’s denim wear and hasn’t changed radically since.

Highsnobiety

As Klein ventured into new product lines, slight adjustments took place in reaction to the new word being added: the small “ck” next to “ONE” on the brand’s ’90s cologne. The original logo was “clean, direct, powerful and beautiful,” according to Fabien Baron, who made only the slightest of adjustment, deepening the gradient, when he joined CK as creative director in 1990.

Traditionally, the suggestive avant-garde stamp would appear in black on high fashion, in grey on jeans, and white on underwear, though the brand has since diversified into a range of colors and arrangements. In 2016, legendary British designer Peter Saville, enlisted following the arrival of Raf Simons at the brand, made the whole thing upper case. The other name Simons premiered, 205W39NYC, is being phased out following his departure, along with the ready-to-wear line of the same name.

Kate Moss was the “anti-glamour” alternative Calvin Klein needed at the beginning of the 1990s. After near-bankruptcy threatened the brand’s future in 1991 – it was bailed out by music magnate David Geffen – Klein sent the teenage model on vacation with her then-boyfriend Mario Sorrenti, who produced a clutch of intimate snaps that became her first campaign in 1992 and inaugurated a partnership that lasted eight consecutive years. The couple soon broke up. “I’d wake up in the morning and he’d be taking pictures of me,” Moss explained to Nick Knight. “I was like, ‘Fuck off!’ I lay like that for 10 days. He would not stop taking pictures. But, he’s Italian, you know? He was like, ‘Lay down, I’ll tell you when we’ve got it!’ We probably had it in the first roll.”

Getty Images / PL Gould

Few corporations have exhibited such flair for controlling and directing public anguish, spinning even minimal controversy into marketing and commercial spoils, as Calvin Klein. Over the years, Klein has hired some of fashion’s best-known narrative strategists – figures who both defined and shifted the message around clothes and knew how best to handle their former coworkers.

In 1975 he hired dandyish Franco-Russian socialite and Vogue senior editor Baron Nicholas de Gunzberg, whose perspective on American fashion had helped Klein find his voice in the early ’70s. The following year he brought in Frances Stein, also from Vogue, to join his creative team, while Grace Coddington was imported from London to act as design director. One of Klein’s early jobs was as a copyboy at WWD and it’s not impossible his early exposure to the media stuck in his impressionable mind. Speaking to Andy Warhol in an interview, Klein spoke of his relationship with de Gunzberg:

Getty Images / Robin Platzer

I begged Nicky de Grunzberg in the last years of his life to write a book … God knows, Nicky was surrounded by incredible people all his life – Noel Coward and Cole Porter and Chanel. His family subsidized the Ballets Russes. He’s seen it all. I got to know him in his sixties. He said that whenever we go the first time to a restaurant he pays. Every other time we go I pay. So he said, “Where do you want to go first?” I said, “La Grenouille.” We went to La Grenouille and had an absolutely marvelous lunch as we sat on a banquette. We were finishing dessert and he said, “Now Calvin, I want you to tell me what you think and what you see.” I said, “God, Nicky, the flowers are incredible and the people look so beautiful and there’s so much elegance and the food is superb.” He said, “Just remember, in minutes it all turns to shit anyway.

Obsession is a spicy amber fragrance launched in 1985, just as the decade hit its decadent peak. It comes in a little pear-shaped orb, designed to capture the glow and bombast of the age. “The name Obsession is big, like a movie poster for this era,” Klein told Vanity Fair. “I think of everything I’ve ever done, how obsessed I was. Everyone was obsessed in the ’80s.”

In the early 2000s keepers at the Bronx Zoo reported that wild cats – tigers, leopards, jaguars – responded strongly to the scent. Pat Thomas, General Curator at the zoo reported how it would “encourage this really powerful cheek rubbing behavior where these big cats would wrap their paws around a tree and just vigorously rub up and down. Sometimes they would start drooling, their eyes would half-close, it was almost like they were going into a trance.”

As reported in the Guardian, rangers in the Indian state of Maharashtra adopted the scent in trying to track down a tiger named T1, thought to have killed a score of local people. The key ingredient is a synthetic alternative of the musk secreted by a civet – a small Asian mammal whose glands produced a prized aroma and regularly finds itself prey to big cats.

It seems the perfumer nailed the desired effect, the name itself proving iconic and finding its way onto apparel over the years.

Calvin Klein’s preferred design logic of minimalism, reduction, and aesthetic purity stemmed from emerging trends in architecture and visual art in the early 20th century. He cites artists Richard Serra, Agnes Martin and Donald Judd as key influences, along with architects Tadao Ando and Mies van der Rohe. Much like one of Ando’s brutalist structures, which are calmly integrated into the Japanese landscape, Klein’s designs were intended to frame, support and amplify the body, goals the designer sought to achieve through removing elements rather than adding them.

Getty Images / Trevor Gillespie

“I believe in paring something down to its essence, where line, color, and form are all,” Klein says. “There is beauty in simplicity, grace in understatement.”

On age:

“People in their 70s can still have incredible lives. Health is the most important thing.”

On bootlegs:

“It’s when they stop copying, that’s when we’re really in trouble.”

On his name:

“It’s fun seeing my label on someone’s behind — I like that.”

On authenticity:

“I invited controversy throughout my career because it was born of authenticity and integrity. I never sought to shock for shock’s sake. I had one vision: to speak of the timeless seduction of youth – those fiercely creative individuals who answer only to themselves. All these years later, the images still hold the power to stroke passions and stir emotions.”

Getty Images / Peter Turnley

When Belgian designer Raf Simons joined as chief creative officer in 2016, the brand attempted to unify its disparate product lines under a single vision – the way it had under Klein – emulating the major European houses.

Highsnobiety / Thomas Welch

Simons deployed his subcultural sensibilities and decades of experience as one of the world’s foremost designers under his own name and at Dior to give the American brand a more unsettling, inventive, political edge. He launched the ready-to-wear line Calvin Klein 205W39NYC, tunneling through the brand’s archive and the darker side of American pop culture, making his brand debut at New York Fashion Week in 2017 with David Bowie and Pat Metheny’s “This is Not America” oozing out of the soundsystem. Sculptures, flags and other decoration from the workshop of Sterling Ruby, who also renovated the brand’s flagship store on Madison Avenue, hung from the ceiling. Faux fur, synthetic plastic overcoats, and steel-capped “CK” cowboy boots suggested the darker, industrial and wasteful underside of the American dream – the perfect counterpoint to years of boundless optimism from Klein.

Highsnobiety / Thomas Welch

Simons’ final show in 2019 invoked the unknowable realm of the sea – submerging guests on blood-red seats for a show that featured deconstructed wetsuits, red sailor beanies and the movie poster for Jaws as its central motif. But as Vogue noted upon the designer’s breakup with the company, the numerical challenge proved insurmountable, even for a visionary like Raf. “In 2014, global retail sales of products sold under the Calvin Klein brands were approximately $8.1 billion. Insiders questioned how Simons, who has an immaculate high fashion CV, having turned out cerebral clothes at gilded houses such as Jil Sander and Dior, would cope with total control over the mass-market behemoth that at the time comprised Calvin Klein Collection, Calvin Klein Platinum, Calvin Klein, Calvin Klein Jeans, Calvin Klein Underwear and Calvin Klein Home brands – brands which he was charged with unifying under one creative vision.”

Probably the most notorious campaign in the brand’s anthology of provocative media is photo legend Steven Meisel’s 1995 work for Calvin Klein Jeans. To some, the innocence of the models and the wood-panelled interior suggested amateur porn. Parent groups, the Catholic League and even presidential incumbent Bill Clinton compelled the Justice Department to investigate what they claimed could be child porn, though the brand soon provided evidence that the models were of age.

Another angle on what provoked Americans most about the ad – class, not sex – came from Richard Martin, former curator of the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

Here Klein represented class, the taboo subject. The insolent, indifferent kids of the August campaign parallel the young people of Larry Clark’s photographs and recent film “Kids.” Klein was not concocting a dream in utopian physique or sun-drenched paradise. He led us away from fashion grandeur to trailer-park trash, the rude and surly kids of their own abject world. No one may admit that there is class, much less a lower class, in supposedly classless America. Who is staying home watching trash television? The tacky faux-wood paneling shows us the tawdry world of lower-class kids in America today.

Richard Martin, The LA Times

Getty Images / James Leynse

Advertising scandals to one side – Klein himself was able to excite the tabloid press with nights that were just as tightly scheduled as his days. Infamously, the designer once wandered out onto the court during a basketball game in 2003. As the New York Times reported: “The fashion designer Calvin Klein said yesterday that he was seeking professional help for substance abuse, nearly two weeks after his erratic behavior during a Knicks basketball game at Madison Square Garden briefly forced a halt in play.

The incident, in which Mr. Klein seemed to try to engage Latrell Sprewell in conversation as the Knicks player was about to throw the ball in-bounds, raised questions about the designer’s health.” Klein checked into rehab shortly afterwards.

The incident led the New York City Council to pass a law known as the “Calvin Klein bill” which hiked fines for sports fans who interfered with live games.

Calvin Klein began producing underwear in 1982, disrupting a conveyor belt of bland, industrial products by sexualizing them on the world stage. The first innovation was the logo band: an inch-thick ticker-tape perfectly positioned for the trend that saw jeans grow baggier and waistbands sink lower over the coming decade. The design remains iconic, and though regularly imitated, will forever be associated with the brand.

Klein was out driving when he spotted the Brazilian Olympic pole vaulter Tom Hintnaus running on LA’s Sunset Boulevard and pulled over to ask if he’d ever modeled. Paired with photographer Bruce Weber, Hintnaus starred in a campaign hailed by American Photographer as having “liberated male sexuality” and saw his bulge loom over Times Square. Bus shelter advertising windows were smashed by people who wanted to take the poster home – a cost Klein offered to cover.

Back when Mark Wahlberg was Marky Mark, the rapper helped Calvin Klein launch a new kind of garment – the boxer brief. Klein cast Wahlberg in a 1992 commercial series alongside Kate Moss after music mogul David Geffen showed the designer a Rolling Stone cover featuring the rapper and later movie star, pants low, brandishing his CK briefs. The new product type was designed by John Varvatos and seemed perfectly suited to Wahlberg’s “incarnation of black hip-hop gestures through a white, boyish innocence.”

Getty Images / Barry King

22 years later, history repeated itself as Justin Bieber attempted to emulate Wahlberg – first by appearing in CK underwear on the cover of Rolling Stone, second by posting himself wearing them on Instagram along with the hashtag #mycalvins. “I have been wearing Calvin Klein underwear for years in hopes of getting to model for the brand one day,” Bieber told WWD. “Last spring, I posted a picture on Instagram in my underwear, using the #mycalvins tag. Thankfully the brand saw it and liked the reaction it was getting, and a relationship started from there.”

Nobody truly knows how spontaneous this was, but Bieber seems to have locked on to Wahlberg’s earlier persona as a means to unveil his newly-grown, ultra-swole physique and to cast off his reputation as a teen icon. Wahlberg was in many ways NSFW. Back in 1992, Klein’s creative team had written a script for the spots, directed by Herb Ritts, but Marky Mark insisted on inventing his own – including one line in particular that has not aged well: “The best protection against AIDS is to keep the Calvins on.”

The three strike rule always applies. Here are three times the Calvin Klein company was visited by the authorities.

2008: A TV spot in which 2 Fast 2 Furious actress Eva Mendes flopped around naked against a bright white backdrop was deemed unsuitable to air and banned by US networks until Calvin Klein recut it – leaking the original online pretty soon after in yet another popular attention coup. French art director Fabien Baron laid the blame at the feet of then-president George W. Bush: “You must be kidding me,” he said, when WWD asked about the ban. “This country really needs a new president – this country is so messed up.”

2010: The Australian Standards Bureau stepped in after billboards in downtown Sydney and Melbourne led to complaints that a 2010 campaign shot by Mert Alas and Marcus Piggott starring Lara Stone amid a group of male models next to a chain-link fence suggested gang rape. The image’s indoor counterpart, which saw Stone and her boys lolling around in a sitting room somewhere, was similarly protested by the American Family Association for encouraging “group sex.”

2016: Harley Weir’s “upskirt” photograph of Danish actor Klara Kristin provoked rage from the National Center on Sexual Exploitation and accusations that it glorified rape culture. Director Dawk Hawkins said “by normalizing and glamorizing this sexual harassment, Calvin Klein is sending a message that the experiences of real-life victims don’t matter, and that it is okay for men to treat the woman standing next to them on the metro as available pornography whenever they so choose.” “Upskirting” became illegal in the United Kingdom as part of the Voyeurism Act in April 2019 and is already outlawed in numerous US states.

In March 1968, Klein rented a tiny room at the York Hotel on Seventh Avenue, which would be his atelier as he composed his first collection. Barry Schwartz, Klein’s friend and business partner until the pair sold Calvin Klein Inc. to clothing conglomerate PVH for $400 million each (plus royalties) in 2006, had returned from the army in 1964 when his father was murdered while working at the family’s grocery store in Harlem.

Getty Images / Joan Adlen

The following month, April 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Tennessee and riots spread throughout the country. Klein and Schwartz rushed to the wrecked Harlem store but decided not to save it. Having already siphoned off start-up cash to invest in his friend’s vision, the next day Schwartz joined Klein at the hotel where he would begin formally managing the business. In retrospect, it almost seems like fate that Donald O’Brien, Bonwit Teller’s general merchandise manager, exited the elevator on the wrong floor later that year, spotting the Klein workshop by accident and was drawn to what he saw. The first private jet the company would buy was named for the number of the room: “613CK.”

“When I do a collection I think about the things men would want to wear,” former creative director at Calvin Klein Collection Men’s Italo Zuchelli told 032c in 2011. “On the other hand, when I do a fashion show I have to create a fantasy. My ideal is to reach a perfect balance. It’s like a perfect pop song. It is the most difficult thing to achieve for an artist.”

Between 2004 and 2016, Zuchelli’s reign at Calvin Klein brought the sort of tech and utility thinking more commonly associated with sportswear or Apple’s Industrial Design Group to the testosterone-rich world of men’s tailoring. In his collections, he aspired to the fulness of masculinity he had detected in Weber’s photographs of Tom Hintnaus (a campaign he spotted in L’Uomo Vogue as a young man), sprinkling in a note of humor (Zuchelli hoped to eroticize leggings the way CK had done briefs), and testing the limits of the brand’s traditional remit. Working alongside Klein, he observed an American pragmatism – a sense of perspective Klein never lost.

I worked with him for three years and it was an amazing relationship. He always knew if he liked something or not. He solved things without compromise. I am similar in that sense. He was very quick. He made decisions almost immediately, which is very American. Europeans can be philosophical about things, but these are clothes! His response was very good, it was the main thing that allowed me to go in one direction or the other and then apply my European sense to make it the best possible. I learned the immediacy from him. I never heard him say, ‘I don’t know’… ever.

Italo Zucchelli