Boris Johnson Meets His Destiny

Late morning on Tuesday, July 23, the denouement in Boris Johnson’s lifelong quest for political power will be revealed, when the committee that has organized the Conservative Party’s leadership election will announce the winner of the race to replace Theresa May. The following day, the winner—Johnson is the heavy favorite—will be driven to Buckingham Palace for an audience with the Queen, and be formally appointed prime minister.

It will be the culmination of seven weeks of national campaigning in which Johnson has slowly and cautiously closed in on the prize. Yet in reality it has been a 40-year pursuit, relentlessly driving forward, each step a mere prelude to the next on his seemingly unstoppable rise.

There was his two years as foreign secretary, resurrecting his career following a failed initial bid at the top job in 2016; before that, his two terms as London’s mayor, the first (and only) Conservative to win the position in Britain’s left-leaning capital, during which time the city hosted the 2012 Olympics; and his time as a member of Parliament and journalist before that, all building to this point. He has often stood apart from his party’s leadership, and grown more powerful each time. Here is a man unshackled from the constraints that usually apply—one whose personal celebrity has given him autonomy from a party that has instead come to rely on him to save it from annihilation as a result of the one policy, Brexit, he was instrumental in bringing about.

And yet, despite decades in the public eye as one of the few internationally recognized British political figures, a national celebrity in his own right, the Boris Johnson that stands on the brink of power is still far more known than understood. The early events that shaped him—his ambition and intellect, independence and comic persona—are veiled by his own reluctance to speak about them.

To some of those who know him best, the most important period in Johnson’s life was not his time as foreign secretary or as a leader of the Brexit campaign; nor his time as London mayor or in journalism. The period that his own mother has said was crucial in the early molding of Johnson’s character came when he was just 10 years old. It is a period of his life he rarely talks about, one that holds a wound apparently too deep and too personal.

Then going by Alexander—his full legal name is Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson, or Al as he is still known to his family—Johnson had been living in Brussels with his parents and three younger siblings: a striking clan of blond, bohemian intellectuals wrapped tightly together by their warm, loving, and artistic mother, Charlotte. This scene is laid out in colorful detail in two major biographies of Johnson. (Neither Johnson nor any of his immediate family spoke with me for this piece, but several friends and former colleagues of his did.)

Charlotte had been the center of the children’s lives, the one constant in a peripatetic childhood in which the family shifted from one continent to the next—moving 32 times in 14 years—following their father, Stanley, and his ever-changing work in academia and institutions such as the World Bank and the European Commission. The upheaval, coupled with Stanley’s long absences, in which he would often leave the family for months at a time, had strengthened the bond between the children and their mother. They had shared idyllic periods of stability: a life and home in Washington; time on the family farm in Exmoor, southwest England, where Charlotte homeschooled the children; and then later in the comfortable, bourgeois Uccle suburb of Brussels, attending the local French-speaking European School.

It was at this moment, in Brussels in 1974, that Charlotte suffered what her family has described as a mental breakdown, forcing her to leave her children and return to England for psychiatric treatment. She would spend several months at the Maudsley Hospital in South London; while there, she produced a cascade of vivid and sometimes disturbing paintings, collected in a book now kept in the British Library. In one, Hanged by Circumstances, Stanley, Charlotte, and the four children, all easily identifiable, are hanging by their arms with pained expressions on their faces.

Life had been upended for the Johnsons. While Charlotte would rejoin the family, she would continue to suffer health problems for the rest of her life: depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder, which manifested as a fear of dirt, and then Parkinson’s disease when she was just 40. A year after their mother’s breakdown, Johnson and his sister were sent to boarding school in England, traveling together, alone, across the English Channel. He was 11.

Three years later, right before Christmas 1978, Stanley and Charlotte’s marriage collapsed, just as their son was settling into his life at Eton, the exclusive boarding school and training ground for Britain’s elite. Charlotte would later describe Stanley as “completely unfaithful,” speaking to the journalist Andrew Gimson for his biography of Johnson. Another of her paintings depicts “Dark Stanley.” The family was in enormous pain—“I was so, so close to the children,” Charlotte told Gimson, “and then I disappeared.”

In these few years, the young Alexander’s world collapsed and a new figure began to emerge. The quiet and bookish child, who would say to his siblings “Let’s play reading” when asked to come up with a game, would soon completely transform into the famous figure he is today. Alexander, the boy born in Manhattan and raised as much in the United States and Europe as Britain, had become Boris the eccentric English jester.

This is the Boris Johnson who would go to Oxford to study classics, before embarking on a stellar—and controversial—career in journalism, first being fired from Britain’s The Times before joining its rival The Daily Telegraph, where he became Margaret Thatcher’s favorite journalist as the paper’s chief Brussels correspondent, helping to set the Conservative Party alight with (often dubious) stories of European Union bureaucrats undermining British sovereignty.

This is the Boris Johnson who would become editor of The Spectator, Britain’s top conservative weekly, a position he held on to after winning election to Parliament, turning himself into a media celebrity through a series of now-trademark blunderingly comic performances on the prime-time BBC satirical quiz show, Have I Got News for You.

Johnson attends a Conservative Party leadership debate. (Peter Nicholls / Reuters)

Johnson attends a Conservative Party leadership debate. (Peter Nicholls / Reuters)

This is the Boris Johnson who was promoted to positions of prominence in the Conservative Party, only to be dismissed for lying about an extramarital affair; who twice won the mayoralty in London, one of the most cosmopolitan cities on Earth, and then successfully led what critics said was a nativist campaign to take Britain out of the EU against his old friend David Cameron.

And this is the Boris Johnson who was central to bringing down Theresa May as prime minister, finally putting him within striking distance of 10 Downing Street—the dream he’s held since Eton, according to family and friends as recounted in both major biographies.

Ultimately, no one can know how the experiences of his childhood affected Johnson, in either his adolescence or his later life, nor how much of his character was shaped by events rather than simple biology. His three siblings—part of London’s media or political elite in their own right—are different from him in their personalities and ambitions: publicly and privately critical of his behavior, opposed to Brexit, some reserved, some outgoing. Boris shares many of his father’s personality traits, while family friends suggest he has inherited his mother’s sensitivity and artistic flair.

Yet, whether nature or nurture, this transformation from Alexander to Boris lies at the heart of the man who is likely to become British prime minister. This is Boris Johnson the enigma: the American Englishman, born in the New World but raised in the traditions of the old; a genuine intellect wrapped in a veneer of buffoonery; someone who has dismissed Donald Trump as “clearly out of his mind” and betraying a “quite stupefying ignorance,” yet remains on friendly terms with the notoriously thin-skinned president; a self-confessed megalomaniac who shies away from confrontation; a disheveled mess who bumbles from one success to the next.

Here is a man with a yearning to be loved—a “neediness” in the words of one biographer—that can reveal itself in a jaw-dropping recklessness, a “man-child politician” seemingly unable to control himself yet at the same time intensely focused. In his hands, Britain now finds itself in a moment of maximum danger—and opportunity.

In the Marx Brothers’ 1933 comic masterpiece, Duck Soup, the anarchic leader of “Freedonia,” Rufus T. Firefly, prosecutes the Freedonian spy Chicolini. “Gentlemen,” Firefly declares to the jury, “Chicolini here may talk like an idiot, and look like an idiot. But don’t let that fool you. He really is an idiot.”

In 2010, Jeremy Clarkson, then the presenter of the BBC’s Top Gear—a car-review show that is wildly popular around the world—took a similar tack when he spoke with Johnson on the program. “Most politicians, as far as I can work out, are pretty incompetent, and then have a veneer of competence,” Clarkson said to Johnson. “You do seem to do it the other way round.” Johnson, in his characteristic amused stutter, replied: “You can’t rule out the possibility that beneath the elaborately constructed veneer of a blithering idiot, there lurks an, er, blithering idiot.”

This most fundamental of questions—who is the real Boris?—remains up for discussion, even as he prepares to become Conservative Party leader and British prime minister. Is it all an act? How can someone so smart seem so clownish?

The U.S.-polling expert Frank Luntz, a friend of Johnson’s at university, told me he was a particularly difficult politician to work out. “Boris is so hard to understand because there really isn’t anyone like him on either side of the Atlantic,” he said in an email. “I’ve never met someone so obviously talented yet so quickly dismissed by critics because he doesn’t conform to their definitions or expectations.” Luntz said that while the pair were at Oxford, Johnson would confound opponents in a debate by ignoring the usual rules. In one instance, to combat a motion condemning Israel at a university debating society, instead of rooting his argument in history or modern politics, Johnson talked about being bullied. “The place,” Luntz wrote, “was mesmerized.”

The reality is, people are rarely entirely real or entirely fake—life is more complex.

Philip Corr, a psychology professor at London’s City University, told me Johnson was far from unique in developing new personality traits to help him get by. One way of responding to a major trauma in childhood—or the simple reality of a new environment, such as a boarding school—might be to take on a different character. “If you take on this character and it works, then there’s positive reinforcement, and you keep doing it,” he said. “You end up being the person you create.”

If this is true of Johnson, the pattern is easy to spot. In Brussels, he was fluent in French and described by one teacher as un enfant doué—a gifted child—and later won the most prestigious merit-based scholarship to Eton. “I don’t think I’ve ever taught anyone who learned quicker,” Clive Williams, a teacher of his at Ashdown House, the boarding school he attended before Eton, recalled in Gimson’s biography of Johnson. Williams described how other teachers would discuss the new “fantastically able boy” in the common room and how they had noticed something “rather special” about him.

At the beginning of his time at Eton, report Gimson and Johnson’s other biographer, Sonia Purnell, he continued to be known as Al or Alex, a King’s Scholar and self-confessed nerd who excelled at subjects such as Greek, Latin, and the classics. Even recently, when his siblings and their children were gathered for a beach barbecue while on vacation, Boris was found tucked away behind a rock reading Roman history, the family friend Mary Killen wrote in Tatler magazine. As an adult, this side of him still remains.

His dominant persona, however, changed at Eton. Over time, his popularity grew and his reputation as an academic wunderkind fell off. He was appointed captain of the school in his final term, making him “constitutionally the top boy in the whole school” according to Eton’s public glossary, and confirming his new status as “a fully fledged school celebrity known to everyone simply as Boris for the first time in his life,” Purnell wrote. “Here was the near-perfect prototype of the seemingly bumbling, shambolic persona wrapped round the rapier intellect that we know today.”

This dichotomy is shown again and again in accounts of his time at school. In the battle between the need for popularity and academic achievement, the former was winning. In a report sent to Johnson’s father in 1981, Martin Hammond, one of Johnson’s teachers at Eton, wrote, “Boris’ favoured pace is the amble (with the odd last-minute sprint), which has been good enough so far and I suppose enables him to smell the flowers along the way.”

The trend continued at Oxford. There, he would join the Bullingdon Club, the most exclusive and riotous aristocratic drinking society at the university. He edited the satirical magazine Tributary and stood twice for the Oxford Union presidency, winning the second time around, with Luntz’s help. And he dated, then married, Allegra Mostyn-Owen, who had graced the cover of Tatler.

But perhaps nothing sums up the Johnson model more than his pursuit of the highest honor in a British undergraduate degree, a first. In Johnson’s case, that involved a last-minute “sprint” founded on his raw intellect, but he fell just shy of the grades required. He’d wanted it all, but had, in the words of Hammond, stopped too long to smell the flowers.

“My silicon chip has been programmed to try to scramble up this cursus honorum, this ladder of things.”

Matthew Bell, a journalist who worked at The Spectator when Johnson was the editor, told me this was typical of Johnson. “It was a constant essay crisis,” Bell said, recalling his five years at the magazine that overlapped with Johnson’s time there. “But he thrives under pressure.” Johnson could be “maddening” to work for but inspired enormous loyalty. “One of the most interesting things about him is, it’s very hard to dislike him when you’re in his orbit. Everyone who works with him loves him. However lowly you are, he has that Bill Clinton ability to make you feel special.”

Johnson, in this way, can be both the chaotic center of attention and the bookish introvert he was before his mother’s illness; the act could well be an act, but is no less real because of it. Everyone acts. One side of his character is not fake and the other side real; they are both genuine and important parts of who he is.

The real question, perhaps, is not whether he is a fraud, as his critics claim, but what happens if the tricks that have worked throughout his life, making him both popular and successful, no longer work as prime minister? What then? From the fire of 10 Downing Street—as Britain grapples with Brexit, its shifting standing in the world, and a host of domestic challenges—what will emerge?

Boris Johnson is, of course, not alone in suffering a major trauma in his childhood, even among high-level politicians. In fact, it is remarkably common.

In the 1970s, the Jamaican-born writer and broadcaster Lucille Iremonger published an influential book noting the high proportion of British prime ministers who had lost a parent in adolescence: 25 out of 40, from Sir Robert Walpole in the 18th century to Neville Chamberlain, the prime minister at the start of World War II. “Not only had many of these men suffered the traumatic and unusual experience,” Iremonger, who later became a local councillor with the Conservatives, writes. “So many demonstrated the most powerful drives for attention and affection.”

Recent prime ministers have undergone early traumas in their life as well: Tony Blair lost his mother at university. Theresa May lost her parents in quick succession when she was in her 20s. A similar trend has been discovered in U.S. presidents, with 12 having lost their fathers while they were young, including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama.

Many of these leaders were ambitious, isolated, detached. In Iremonger’s book, The Fiery Chariot, she posits that a parent’s death is just the most extreme example of the “deprivation of love” in childhood, which often imbues exceptionally gifted children with a ferocious ambition in later life. Winston Churchill, one of Johnson’s heroes, did not lose his father until he was 20, but suffered a childhood of abandonment before that time, as revealed in a series of heartrending letters to his mother in which he pleads with her to reply to him. His father was a towering political figure who appeared constantly disappointed in the younger Churchill.

Clinton, another example, never knew his father, who died three months before he was born; he’d married Clinton’s mother despite being married to another woman. The president took the name of his stepfather, a gambler and an alcoholic who regularly abused his mother. Iremonger writes, “If love, in fact, is denied to an infant, he cannot accept it later, though his need for it is almost insatiable. The process is unconscious but inescapable.”

Johnson, of course, has not lost a parent. He has enjoyed a life of remarkable privilege: educated at two of the most prestigious institutions in the world and surrounded by wealth. Still, in the odd, unguarded moment, some of those close to Johnson have speculated about the root of his burning ambition, of how he would jokingly say he wanted to be “world king”—or even U.S. president, by dint of his birth. Charlotte gave a rare interview to the BBC for a 2013 documentary, and spoke of her illness’s impact on Boris. “I often thought that the idea of being a world king was a wish to make himself unhurtable, invincible, somehow, safe from the pains of life, the pains of your mother disappearing for eight months, the pains of your parents splitting up,” she said. Purnell writes that Johnson has told girlfriends his way of coping was to make himself invulnerable “so that he would never experience such pain again.”

Johnson; his sister, Rachel; and their mother attend the launch of one of his books, in 2014. (David M. Benett / Getty)

Johnson; his sister, Rachel; and their mother attend the launch of one of his books, in 2014. (David M. Benett / Getty)

Luntz is skeptical of such explanations. “He had no more or less ambition than anyone else in the Oxford Union,” he said. “He was just better at it than they were.” The Conservative lawmaker Nadine Dorries, one of his earliest supporters who cried when he pulled out of the party-leadership race in 2016, is similarly dismissive. “Nobody becomes prime minister without having their eye on the ball and going for it,” she told me. “You could say the same thing about any of the leadership candidates who put themselves forward.”

Yet Johnson himself has given some credence to the Iremonger analysis, though it is unclear whether he has read her book. “My silicon chip,” he told the host Sue Lawley in a 2005 episode of the BBC radio program Desert Island Discs, “has been programmed to try to scramble up this cursus honorum, this ladder of things.” The latin phrase is a reference to the Roman political ladder, which had to be climbed en route to the consulship—the greasy pole of antiquity.

Johnson admitted to Lawley that he was “propelled by an egomania, a desire to go on, get on, have a go.” In the interview—the closest Johnson has come to publicly admitting the ferocity of his ambition—he said that characteristic was what kept him “grasping” for the next opportunity, as he put it, never satisfied with where he was. “It’s a sense of you might as well do it, ‘There it is,’ ‘What’s life for?,’ things passing; you’ve got the great dandelion clock of eternity, you know, things are ticking away, why not?”

In the decade and a half between leaving Oxford and his election to Parliament in 2001, Johnson worked as a journalist, a job he used to turn university fame into national notoriety. After divorcing his first wife, he got together with Marina Wheeler, a lifelong family friend. The pair had four children in six years, but soon after the birth of his fourth child, Johnson began an affair with Petronella Wyatt, a writer at The Spectator, where he was by then the editor. (That relationship would later break down in acrimony after an abortion and scandalous newspaper headlines.)

Despite the controversy, though, Johnson was flying. As the Conservative Party floundered in the face of Tony Blair’s seemingly invincible election-winning machine, Johnson had established himself as a breakout celebrity-politician: one of the few likable Tory lawmakers with his own base as editor of a powerful magazine.

Early in his time holding the twin roles, when he finally appeared to have it all, he was racing through the Sardinian countryside in a rental car, midway through a family holiday, to interview Silvio Berlusconi, the flamboyant, billionaire prime minister of Italy, for The Spectator. Getting out of the car, Johnson wandered over to the publication’s Italy correspondent, Nicholas Farrell, wearing a pair of knee-length shorts, a crumpled shirt, and a jacket he’d brought with him from home, Farrell recalled to me, laughing at the memory.

The two had been invited to Berlusconi’s infamous resort to interview the Italian leader. Once through security, they were greeted by the man himself in equally eccentric attire: “A white see-through pajama-type outfit,” as Farrell described it. (Johnson wrote in his piece of how the Italian prime minister’s nipples were visible through his shirt.)

Johnson’s interview, titled “Forza Berlusconi!,” amounted to an endorsement of the businessman turned politician as the best person to lead Italy. “The richest man in Europe is gripping me by the upper arm,” Johnson wrote. “His voice is excited. ‘Look’ he says, pointing his flashlight. ‘Look at the strength of that tree.’” The olive tree he is pointing at has grown from a crack in a boulder “like some patient wooden python” and has split the rock in two. To Johnson, this is a metaphor for the force of Berlusconi’s personality, his “green fuse.”

Though Johnson has gained a reputation for backtracking on spoken remarks or dismissing questioning of his comments as overly literal, his writing, particularly earlier pieces, offers an insight into his mind-set and priorities, and this article is a prime example. It is classic Johnson: factually inaccurate in parts—Berlusconi was not the richest man in Europe—and a paean to personality and its ability to shape the world around it. Who else could he have in mind?

Johnson appears to be in awe of Berlusconi, his persona, and his palace. Here is a 21st-century Crassus in all his opulent absurdity. To Johnson, the appeal of the man is not his politics but his raw energy, his “torrential loquacity” and “fantastic volcanic, American self-propulsion.” He stands for “optimism and confidence.”

As in much of Johnson’s writing, intended or otherwise, he seems to go out of his way to invite comparison. The great-grandson of a murdered Turkish politician, Johnson says Berlusconi’s appeal is that he is “a transplant.” He writes, “Suddenly, after decades in which Italian politics was in thrall to a procession of gloomy, portentous, jargon-laden partitocrats, there appeared this influorescence of American gung-hoery.”

To Johnson, this “American gung-hoery”—or energy—is the essence of a man. “Intelligence is really all about energy,” he told an interviewer in 2003, the same year he met Berlusconi. “You can have the brightest people in the world who simply can’t be arsed. No good to man or beast.”

Johnson’s scabbard, he admits, is instinctively drawn in defense of characters, not political arguments. He is drawn to Berlusconi and other rogues for the power of their personality and is prepared to forgive the rest: the rule-breaking and corruption, the sex and scandal. To Johnson’s critics, this smacks of arrogance and his own unfitness for office—it gives away his sense that life’s rules apply only to the little people. Men of energy and power and greatness are exempt.

“Boris is very charming, very plausible, but cuts fast and loose with the facts.”

Another of his colleagues at The Spectator, the copy typist Julia Pickles, who worked for Johnson throughout his six years as editor, recalls the day he arrived at the magazine. He was test-driving a sports car—“this great hunk of very expensive metal” as Pickles describes it—for GQ. Pickles welcomed him in and warned him not to leave the car outside, wary of it getting a parking ticket. “Boris took no notice and bounded off to his room,” Pickles says. “The next minute a large claw descended from the sky.” The car, picked up by a crane, was being impounded. Johnson had not noticed the ensuing disaster—he was on the phone with his lifelong friend Earl Spencer, the brother of Princess Diana—when Pickles burst into his room to tell him. “Oh fuck,” he cried, looking out the window. Pickles remembers thinking life was going to be “quite lively” in the future. “And it was.”

A letter from Hammond, Johnson’s teacher at Eton, to his father, Stanley, gives an earlier glimpse of this tendency. “I think he honestly believed that it is churlish of us not to regard him as an exception, one who should be free of the network of obligation which binds everyone else,” Hammond wrote when Johnson was 17. His largely sympathetic biographer Gimson implicitly accepts this criticism: “What he cares most about is the greatness of Boris, to be obtained without any diminution in the personality of Boris. For him to be bored is a kind of offence against his idea of himself.”

Johnson’s entire pitch for the Conservative Party leadership can be read, in fact, as an argument for the force of character. In his telling, after years of timidity under the dutiful but ineffective leadership of May, the country needs sheer will—not new technocratic fixes—to solve Britain’s ills. In his 2017 letter resigning as foreign secretary, he said the country was being “suffocated by needless self-doubt.”

This is the Johnsonian view of the world: a romantic, egocentric belief in his personal power to do great things, to solve great puzzles, through the force of his personality. He can free Britain from the self-imposed shackles of its Brexit cowardice, building a bridge to France and an airport in the sea.

Johnson’s rare gift is to combine unabashed elitism with popular appeal: for the £180 ($225) bottles of wine and for spaghetti with tomato ketchup; for Homer, his favorite author, and Dodgeball, his favorite movie. It is what makes him the politician, unique in London, able to bond with Will Smith over a joint love of Aristotle.

Smith was the star guest at City Hall in May 2013 at the beginning of Johnson’s second term as mayor—a high-water mark in Johnson’s popularity, having overseen the London Olympics and won reelection the year before. He had been cheered by tens of thousands of Londoners at an event just before the games opened, dismissing “doom mongers” like Mitt Romney who had suggested London might not be ready to host the Olympics.

Standing onstage together, Smith bounced a question from the audience directly to Johnson. “Mr. Mayor, who are your biggest inspirations?”

“Oh my God, arr, you, you mean apart from Pericles of Athens?” replied Johnson, flustered, before shouting, as if he’d only just remembered: “Aristotle!” The answer prompted Smith to note that Aristotle was, in fact, also a hero of his for Poetics, which is widely read by filmmakers. Johnson, not wanting to be outdone, countered that Nicomachean Ethics could have been called The Pursuit of Happyness, one of Smith’s movies.

“We have a lot in common,” Smith said to Johnson, wrapping up the incongruous exchange.

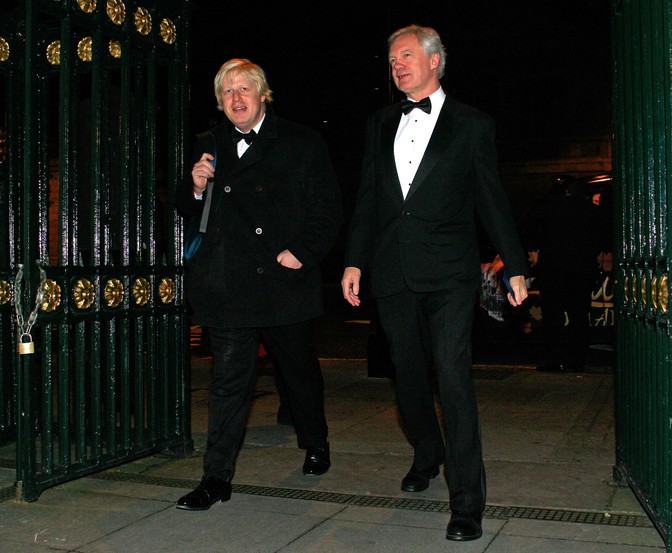

Johnson, then a member of Parliament and the editor of The Spectator, arrives with fellow Conservative lawmaker David Davis at a farewell dinner for the outgoing Conservative Party leader Michael Howard. (Kieran Doherty / Reuters)

Johnson, then a member of Parliament and the editor of The Spectator, arrives with fellow Conservative lawmaker David Davis at a farewell dinner for the outgoing Conservative Party leader Michael Howard. (Kieran Doherty / Reuters)

Smith’s observation reveals more than either of the two men realized. Johnson has an obvious celebrity to him. The pursuit of fame is part of his happiness: the cheers of the London crowd. “They clap, therefore I am,” as Matthew Parris, the newspaper commentator, Johnson critic, and former Tory lawmaker, has written of politicians’ base drive. Yet, power and popularity rarely mix. In pursuing Brexit and the Conservative Party leadership, many of those closest to Johnson during his mayoralty, when he campaigned for amnesty for undocumented immigrants and criticized Donald Trump, say he has abandoned the character the country liked to achieve the power he craves.

But the exchange with Smith also points to another insight: A philosophical seam runs through his career, and he comes closest to laying it out when talking and writing about Pericles, Aristotle, and other ancient Greeks he says he holds dear.

For Aristotle, this pursuit of happiness is best achieved through the pursuit of virtue—an unlikely description of Johnson’s political vision for Britain. Johnson’s love of Aristotle, if taken at face value, instead appears rooted in the power of his intellect and a suspicion of dogma. Aristotle is regarded as the philosopher of the “golden mean,” a moderate who believed in prudence and practicality, not rigid law. This offers a better glimpse of Johnsonian politics: elitist, conservative, and unideological.

Johnson is also distinctly libertarian. In a 2016 debate with Mary Beard, a Cambridge University classics professor, he set out his case for why Greece was more important than Rome. Greece gave us Rome, he said, “just as modern America is the creation of Britain.” Greece gave the world democracy and meritocracy, while Rome ripped it away. Johnson values the “spirit of freedom” in Athens as well as its lack of priggish moralizing, as he sees it. This gets closer to the real Johnsonian idea of a good society: individualism, libertarianism, and democracy. Here people can pursue happiness unimpeded. They can satirize, learn, and worship freely; and the strongest characters and intellects, those with the most energy—people like him—can rise to the top.

This freedom allows him to mock domestic politicians and world leaders, from Hillary Clinton (“sadistic nurse in a mental hospital”) to Barack Obama (“part Kenyan” with a grudge against Britain) to Vladimir Putin (“looking a bit like Dobby the House Elf”). It also allowed him to compose an off-the-cuff limerick about Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan: “There was a young fellow from Ankara/Who was a terrific wankerer/Till he sowed his wild oats/With the help of a goat/But he didn’t even stop to thankera.”

Reflecting on the debate with Johnson, Beard told me she felt the exchange reflected Johnson’s strengths and weaknesses as a politician. “Boris is very charming, very plausible, but cuts fast and loose with the facts,” she wrote in an email. “He does that over Brexit and he did that here.” She said that while it was hard to discern Johnson’s underlying philosophy from the exchange, his style of argument was clear: “Plausible, optimistic, fun and wrong!”

“There was something prurient about the way he wanted to read about his own destruction, just as there was something weird about the way he had been impelled down the course he had followed,” Johnson writes of the lead character in his debut novel, Seventy-Two Virgins.

Johnson continues that “maybe he wasn’t a genuine akratic, maybe it would be more accurate to say he had a Thanatos urge.” (An akratic is someone characterized by a weakness of will, which results in that person making decisions against his or her better judgment; a Thanatos urge is deeper and darker: a death urge.)

The comic novel’s antihero is Roger Herbert Barlow, a 50-year-old, bicycling, angst-ridden Tory backbencher with no real friends, few strongly held beliefs, and only a “knuckle of principle in the opaque minestrone of his views.” While Barlow “lifted the odd pebble from the mountain of suffering that oppressed the losers” of his constituency, that was about it. He only manages to escape the public shaming coming his way by rescuing the U.S. president, albeit in a style owing more to Leslie Nielsen’s Frank Drebin than Jack Bauer.

Johnson published this fictional portrait in May 2004, six months before British tabloids revealed he had been having an affair with Wyatt. At first, Johnson dismissed the claims as “piffle,” only to be sacked from the Conservative Party front bench when they proved to be true.

“If it is lonely at the top, it is because it is the lonely who seek to climb there.”

In the novel, the reader is led to believe that Barlow has had an extramarital affair, only to learn that he had given a woman a large sum of money that she sunk into a brothel called Eulalie—the name of the lingerie shop in P. G. Wodehouse’s Code of the Woosters, which is secretly owned by the would-be dictator Roderick Spode. The lingerie shop is Spode’s “dark secret,” as Johnson previously wrote.

Is Johnson hinting at his own dark secret here, or simply paying homage to one of his literary heroes? That he should even nod at his own private turmoil throughout the book itself exposes a degree of recklessness. During his Desert Island Discs appearance, Lawley, the host, asked Johnson this question. “I think I’m going to take the Fifth Amendment here,” Johnson said to her, again betraying his American outlook by using a legal term that carries no weight in Britain.

“You do like playing with fire though, don’t you? It’s all part of being tested?” Lawley asked again. “I see, this is your theory, is it?” Johnson responded. “Well, I suppose there might be an element of truth in that. Anyway … not unnecessary risks, no.”

When observed from afar, Johnson’s life confirms a pattern of personal and professional liabilities that appear inexplicably rash, yet never knock him off the course he has set himself.

He was fired from The Times for making up a quote from his godfather. Before he even divorced his first wife, his second was pregnant. Throughout his second marriage, he reportedly had multiple affairs, one of which led to a child and two reported abortions. He has become a figure of gossip among Britain’s newspapers, even during this campaign to become Britain’s prime minister: Soon after Johnson’s latest relationship, with a former Conservative Party director of communications, became public, it hit the headlines at the start of his leadership bid that police were called to her apartment following a heated domestic argument.

Still, Johnson’s indiscretions, like Trump’s or Clinton’s, have not yet dented his political aspirations, even if at times they looked to most people as if they might. In fact, The Times—the Rupert Murdoch–owned British paper of the establishment—has endorsed him for Conservative leader.

With such a colorful private life, why does he even risk the public glare of a political life? Why didn’t he stick to journalism, or writing books? “There comes a point,” he told the Conservative Party’s internal magazine in 2001, “when you’ve got to put the dynamite under your own tram tracks … [and] derail yourself.”

In The Fiery Chariot, Iremonger sets out a common characteristic of political leaders who suffered a form of trauma in their childhood: a desperate need for love. So many of these grand figures had, she wrote, in later life demonstrated an immense drive, which led them to a recklessness “hard for less strongly-motivated onlookers to understand.”

It is noticeable how many of those who know Johnson best—or have studied him—talk in strikingly similar terms. His university friend Toby Young, for instance, has said Johnson has “an absolute anathema to being disliked,” adding, “He clearly thrives on popularity and adores winning popularity contests of any description.” Bell, at The Spectator, told me similarly that while Johnson was extraordinarily magnanimous at times—once writing to Young, also a columnist at the magazine who had written a play satirizing Johnson’s love affairs, to say how glad he was that his life had been turned into a farce—he also disliked personal attacks. “He’s quite like Trump,” Bell said, “in that he’s quite sensitive to criticism. He wants everyone to love him.”

From Eton to today, Johnson has entered every popularity contest open to him—and won, eventually. He has triumphed in self-selecting Etonian societies, Parliament, and City Hall, and may soon in the biggest contest of all: that for Conservative Party leadership and 10 Downing Street.

The theory that many of those who yearn for power do so because of anxiety about their own importance has been supported by other leading researchers, including Karen Horney and Harold Lasswell. In a review of Iremonger’s work, the late Professor Hugh Berrington, an expert in political behavior and political psychology at Newcastle University, wrote that “the quest for prestige is essentially a search for protection against insignificance.” Berrington concluded by observing, “If it is lonely at the top, it is because it is the lonely who seek to climb there.”

Some of those who have studied Johnson most closely have homed in on this as a vulnerability they see in him. Is this something the country sees as well—the reason they forgive more from him than other politicians? Gimson, a friend of Johnson’s as well as his biographer, told me there was a “neediness” about him—a sentiment repeated to me by a figure close to Theresa May in 10 Downing Street about his time as Foreign Secretary. “People love him because he makes them laugh,” Gimson wrote in his book. “But also because they glimpse the hurt young kid behind the laughter.”

Peter Guilford, once one of Johnson’s friends and a former journalist for The Times, recalls in Purnell’s book how he was furious with Johnson for badly misquoting him once, only to forgive him quickly after. “I rang Boris and gave him a bollocking. He didn’t fight, he never does—he rolls over and asks for his tummy to be tickled. I went along with it because I didn’t want to spoil my friendship. It’s the same for everyone.”

Iremonger describes the hunger for power among the insecure as the Phaeton complex—the tragic fate of children abandoned by their parents, deriving its name from the Greek myth in which Phaeton, a child of the sun god, demands that the deity prove he is really his father and loves him by letting him drive the sun chariot. When he does, Phaeton’s “utter inadequacy” becomes obvious. He plunges, scorching the Earth and creating the Sahara desert, before Jupiter intervenes to save the planet by striking Phaeton down with a thunderbolt.

The moral of the story is clear. Phaeton’s desire to be acknowledged by his father, Iremonger writes, “in sight of all the world, to the extent even of being allowed to exercise his godlike functions, and his overweening and suicidal determination to display himself to all men carrying out a superhuman task, could lead only to disaster for himself, and possibly for others.”

For everyone close to Johnson who grasps toward this explanation, there are others who dismiss him as simply someone with an inbuilt craving for power or, alternatively, something close to a genius who is simply bigger, brighter, and better than his peers. Others more favorably inclined to him—though remarkably few who spoke with me—believe he is genuinely driven by his vision of the national interest: to make Britain great again.

Johnson is neither clown nor fraud, but a complex individual shaped and driven by a variety of factors: his parents and education, social surroundings, political philosophy, and “silicon chip.” No Poirot will discover the real Boris Johnson, because he has been on display for 40 years, warts and all.

He has been the primus inter pares at every stage of his largely gilded life among England’s elite, for whom charisma, flair, and a love of the classics have counted for much. He is about to enter a world in which speaking Greek matters little; where the cold realities of global power—economic, diplomatic, and military—dominate; where a misjudged joke can spark a diplomatic crisis and a botched decision made in an ill-prepared rush can cost people their life. In this world, of Trump and Xi, Merkel and Macron, Johnson cannot be on top internationally.

As Prime Minister he will stand exposed to the world more than ever before. How will he behave? If the Phaethon complex is accurate, will he continue to flirt with disaster in his private life, unable to resist? In public, will his yearning for affirmation inevitably lead to an early general election, the ultimate test of popularity, power, and recognition? Johnson has insisted this will not be the case. His willingness, unlike more cautious politicians, to “put the dynamite under your own tram tracks” may see him take the ultimate risk of trying to pull Britain out of the EU without an agreement.

Those looking for clues about his plans for office point to his record as one of being remembered for winning more than for what he did once elected. In Seventy-Two Virgins, Johnson’s antihero is held in contempt for his mushy lack of conviction.

Yet Johnson himself has written of the Thanatos urge of politicians. Is he aware of Phaethon? one wonders. In an epitaph on the tragic child of the sun, the Roman poet Ovid writes, “Here Phaeton lies; he who sought to drive the chariot of his father, the sun; if he did not succeed at least he died daring great things.”