Chanel Adds Camellia Drawing to its Arsenal of Trademarks – The Fashion Law

As the story goes, years before Chanel began attaching a single white flower to its black boxes tied up with Chanel-branded ribbons, before its garments – such as the floor-grazing frock that young actress Margaret Qualley wore on the red carpet in at the Golden Globes last year – were dotted with a lone floral accent, and quite a bit before the brand began offering up sparkling, fine jewelry in the shape of delicately-pelated blooms, Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel developed a love for camellias.

It is unclear exactly how the late Ms. Chanel’s affinity for the exquisitely-blossoming flower came about; some point to Alexandre Dumas’ novel La Dame aux Camélias as piquing the designer’s interest in the flower that can be found among the foliage in various regions of her native France. Others suggest that a bouquet from lover Arthur “Boy” Capel was the reason. What is clear is that it did not take long for the designer to begin pinning one of the flowers in her hair or adorning her waistbands and jackets – and ultimately, no shortage of products from her eponymous brand – with a single camellia.

“The camellia was [Ms. Chanel’s] simple, near symmetric wordless calling card, almost as iconic as the linked double Cs, but categorically more symbolic,” as the Independent characterized it not long ago, noting that the flower “has, of course, endured as an emblem of the Chanel house of fashion, beauty and fragrance long after its founder’s death in 1971.”

The brand’s fabric camellias “reportedly take up to 40 minutes to make by hand, each petal a heart-shape folded over to create full blooms,” according to the Independent, while the outline of its petals “appears embossed on make-up palettes, on lipstick bullets, subtly and blatantly, a link to the past and yet perpetually in vogue.”

But more than merely serving as an enduring testament to the house’s heritage, as a result of the frequent and consistent use of the same five-petaled camellia by Chanel in connection with its products, as well as its packaging, the flower has become, in the words of the Telegraph, “one of the most instantly recognizable emblems in all of Chanel’s accessories, clothing and jewelry.” Put another way, the flower, when used in connection with certain types of goods and services, acts as an indicator of source (i.e., a trademark).

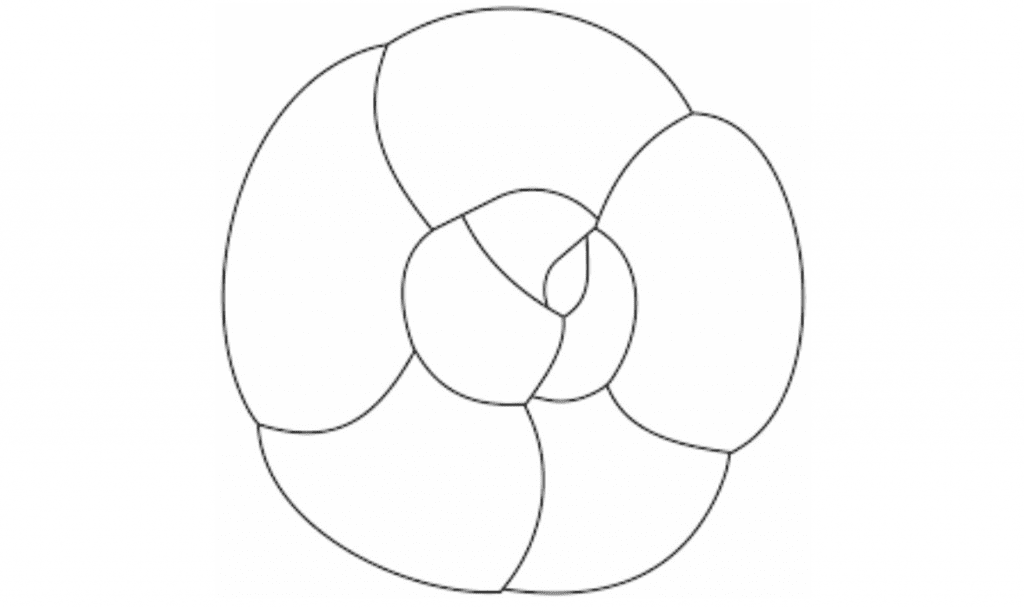

Chanel’s camellia drawing

Chanel’s camellia drawing

Such a notion is not entirely outlandish if the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) has any say, as the national trademark body issued a registration to Chanel for a mark consisting of “ a line drawing of a flower” for use on cosmetics.

Initially skeptical, the USPTO pushed back against Chanel’s trademark application for registration for the flower mark, preliminarily finding that the mark may be “a functional design for the identified goods,” namely cosmetics. Citing case law from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, a USPTO examining attorney stated that “a mark that consists of a three-dimensional configuration of a product or its packaging is functional, and thus unregistrable, when the evidence shows that the design provides identifiable utilitarian advantages to the user (i.e., the product or container ‘has a particular shape because it works better in [that] shape’).” Such a principle is relevant in the matter at hand, as the specimen – or an example of how the trademark is used in commerce – that Chanel provided to the USPTO showed the mark being used on the base of a lipstick applicator.

Chanel responded to the USPTO’s Office Action, asserting that its use of the flower drawing is not functional, and instead, “the sole purpose” of the mark “is to act as a source identifier for consumers.” In fact, counsel for Chanel argued that when it is used on the cosmetic product, the camellia drawing “is used in the same position and manner as Chanel’s other marks, including its [double C] trademark, which is subject to multiple U.S. trademark registrations.”

According to Chanel, “Consumers are well aware of [its] historical use of the camellia flower and understand that it is ‘the’ flower of Chanel,” and that given “Chanel’s historic use of the camellia, there is no doubt that the mark used in connection with the sale of [cosmetics] is uniquely a source identifier associated with Chanel.”

Seemingly persuaded, the USPTO issued a registration to Chanel for the flower drawing in July.

As for whether this registration is part of a bigger plan by Chanel to ultimately claim protection in a 3-D configuration of its specific 5-petal camellia, such as the one that adorns its packaging, time will tell. It is certainly worth noting that the brand has been actively looking to bolster its arsenal of “Camellia”-specific marks in the U.S. and internationally by filing applications for marks, including for “Camelia Chanel,” “Chanel Camelia,” and “Camelia de Chanel.” (In some jurisdictions, those applications have turned into registrations; in others, applications are still in the pre-registration phase).