Coco Chanel—Le Camélia | Classic Chicago Magazine

By Cheryl Anderson

“The seeming simplicity of a masterpiece is sure proof of its grace.”

Chanel

Le camélia, the very essence of simplicity, became one of Coco Chanel’s emblems and among the brand’s signatures—making its official appearance in 1933 on a white trimmed black suit in that year’s collection. The flower’s geometrical roundness, regularity of perfection, and pure white petals appealed to Chanel. Considered a forbidden flower that was both androgynous and ambiguous, without thorns or fragrance, struck Mademoiselle’s taste of provocation.

A Chanel white silk flower with black leaves.

A belief by some, le camélia seduces by its sheer simplicity. Simplicity, from the very beginning, was always an element of Chanel’s designs—simplicity was her definition of beauty. The white camellia has indeed become her emblem and the brand’s signature, but more than simply a logo it evokes the true spirit of Chanel. Danièle Bott states: “The camellia with its minimalist lines, well-defined voluptuous curves, and almost Art Nouveau designs was destined to appeal to her aesthete and as an avante-garde designer.”

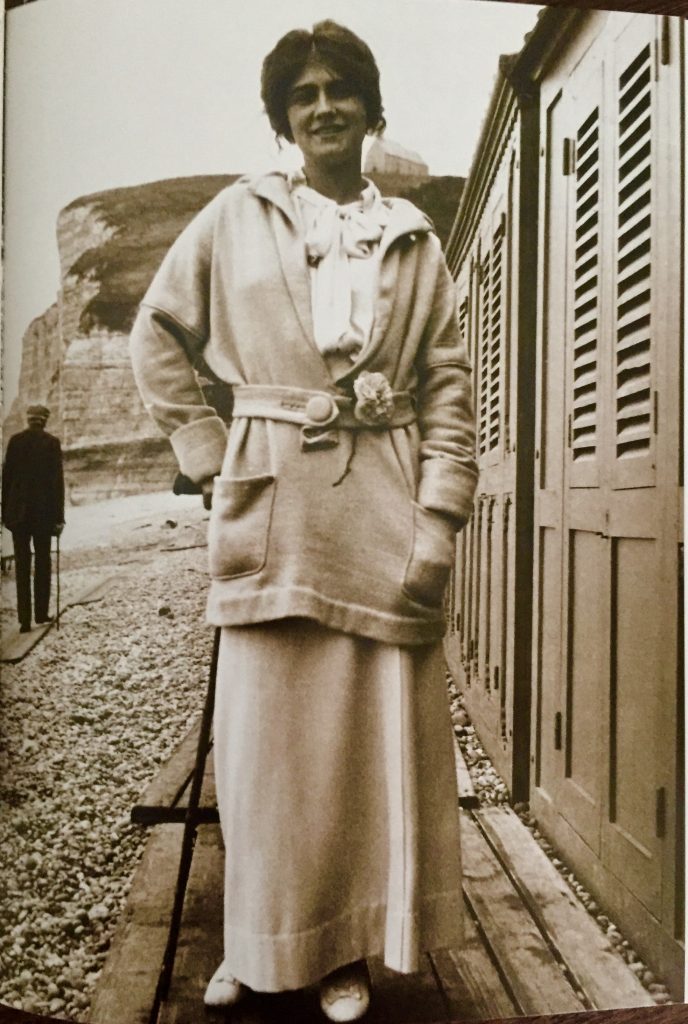

Chanel in Étretat, Normandy 1913. The first known picture of her wearing a camélia.

The use of the camellia in her designs had begun in the 1920s. A stylized camellia was embroidered on a blouse as early as 1922. In 1924, a white camellia was put on a black chiffon dress. On a grey coat with a dropped-waist belt, there was placed a white piqué camellia. In 1934, fabrics with the camellia motif were made for her. Camellias had been appearing on her black dresses and sweaters before the flower’s official launch in 1933.

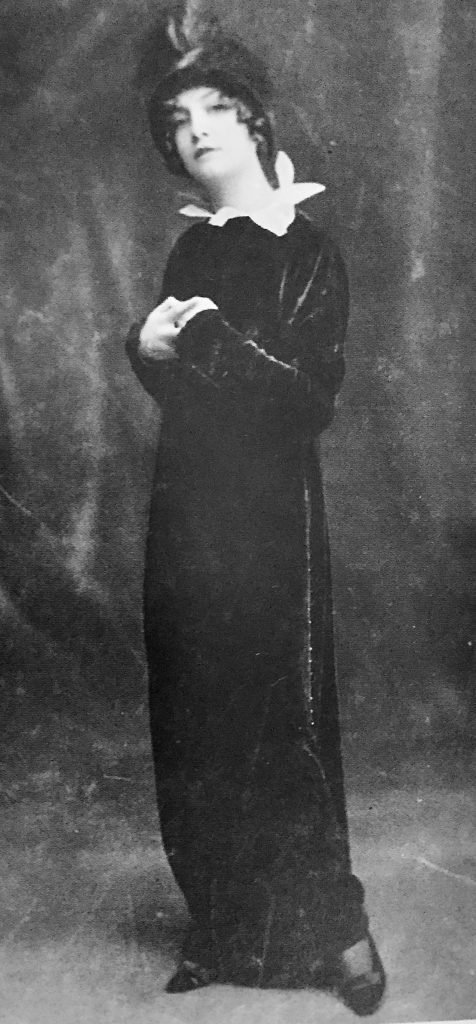

Suzanne Orlandi wearing a black velvet gown with a lawn petal collar.

The courtesan wore le camélia indicating she was available—a symbol of carnal desire. During the Second Empire and Belle Époque, cocottes, originally a term of endearment for small children, was later given to high-class prostitutes from the 1860s—they were also known as demi-mondes. Danièle Bott: “In France under Louis-Philippe and in Tsarist Russia, the Immaculate white flower, so voluptuous yet radiant with purity, accentuated the beauty of women, flattered their décolletés and adorned their hair. They donned the flower as a sign of seduction and flirtatiousness.” Yes, at the time, wearing the flower was shocking, but society and aristocratic women dared to be bold—that coupled with a bit of the frivolous in mind. Proust started the trend of wearing a camellia in his lapel at the Salon de Guermantes. Heretofore, young men wore carnations or gardenias. We know how Chanel was inspired by masculine clothes, so, she decided to borrow the new trend.

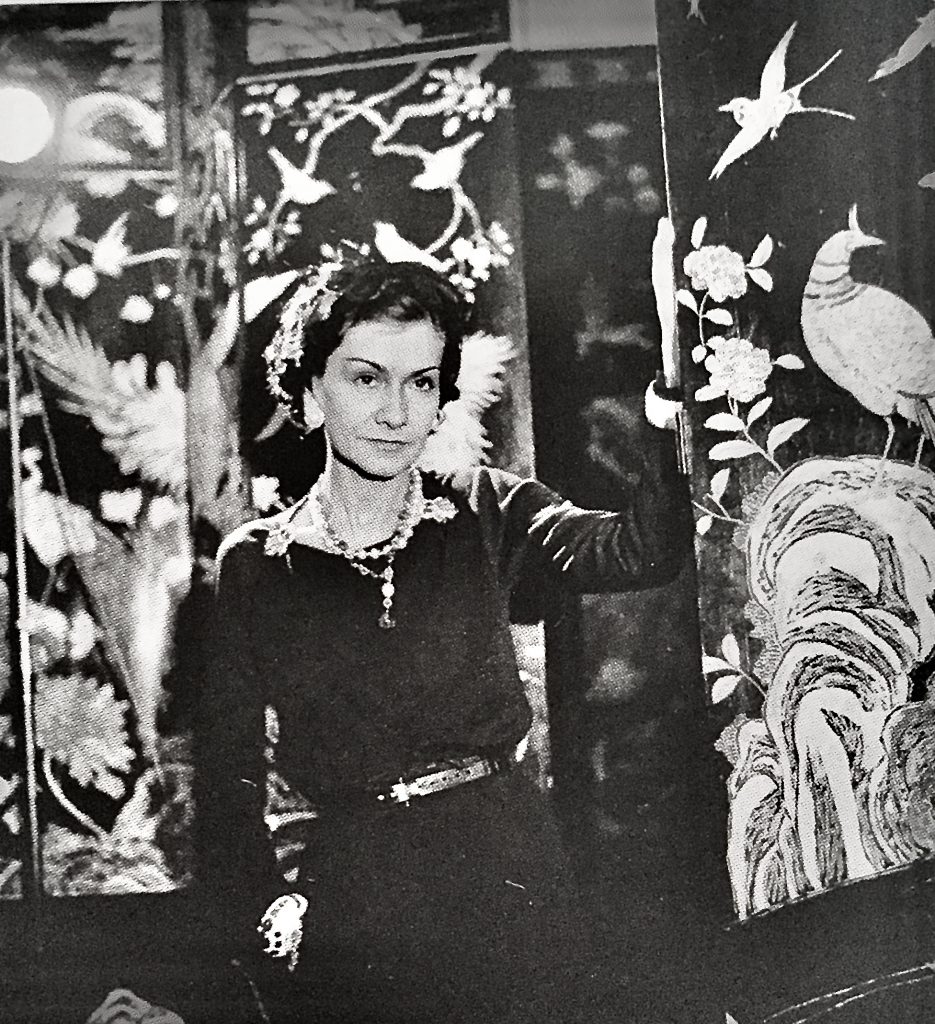

Closeup of camellias and birds carved into one of her Coromandel screens.

An early, and possibly the first, picture of Coco while on the beach in Étretat, Normandy (1913), shows her with a camélia pinned on the waist of a belted jersey suit—a long pullover top with large pockets over a long skirt, with a sailor top underneath. Her hair is parted in the middle and pulled back into a loose bun. She smiled into the camera, and as Bott describes it: ”as if amused by this discreet allusion to seduction, spiced with ambiguity.” One is left to wonder if that was the beginning of what was to become the Chanel flower or simply a flower? Chanel would not allow “Boy” Capel to continue helping her financially after she got her couture house up and running. She no longer wanted to be kept. After two years, she was free from financial obligation— work was what she most enjoyed. Her freedom had been won with hard work.

In that same year, Suzanne Orlandi, wearing what is thought to be Chanel’s first dress design, a long black velvet gown, has a white lawn petal collar. Perhaps, that is her first nod to the idea of her use of the camélia motif. Chanel had her portrait done by George Hoyningen-Huene in 1935. In the portrait, she’s wearing a black jacket with a white ruff—again, almost looking like petals framing her face.

Cecil Beaton captured her image around 1935 standing between two sculpted black servant boys in her home—each with turbans on their heads, each offering her a camellia. Chanel was dressed in a long embroidered lace dress with a chain belt— camellias adorn the veil. Chanel and Salvador Dali are photographed in a relaxed moment, 1937—she’s wearing a checked tweed suit, a black hairband, sautoirs, cuff bracelets, strings of pearls and a large white camellia pinned on the lapel. At that moment, Bott says: “Mademoiselle symbolizes the Chanel look with supreme elegance.”

Chanel in a tweed jacket with Salvador Dali. 1937.

Chanel between two statues presenting her with camellias–there are one or two in her hair. Photo Cecil Beaton.

There are those that say Chanel’s passion for le camélia began when the love of her life, Arthur “Boy” Capel, gave her a bouquet of the blossom. Although, others are of the belief her love of le camélia, could have begun as a child with the allure of the flower in Alexander Dumas’ book, La Dame aux Camélias. In either case, le camélia became a lucky charm in her life. It’s not strictly by chance that she chose le camélia as her emblem, there’s a story behind it, but we will never know for sure what that true story might be.

Mystery, as we know, always surrounds Coco. She would often relate stories about her past history that may or may not be true facts changed from interview to interview. In her infamous words: “My life didn’t please me, so I created my life.” Leaving us, once again, wondering the true story behind what exactly was the allure of le camélia—the allure so powerful that it came to be an emblem the couturier would be known for. A line from Dumas’ book: “Since I am not yet of an age to invent, I must make do with telling a tale. I, therefore, invite the reader to believe that the story is true.”

Portrait by George Hoyningen-Huene in 1935. Charles-Roux says of his friend Chanel, at that time, age fifty five, was in the prime of her beauty.

Danièle Bott: “Twenty-five voluptuous petals wound in a spiral, a sensuous centre, a line inscribed within circle, sensual sophistication, romance tinged with the eroticism that once enchanted the ‘sublime masochist’ and literary heroine Marguerite Gautier…the perfect symbol of subtle androgynous femininity, the very image of Coco’s creations.”

The camellia comes from Native Asian shrubs with shiny oval-shaped leaves that surround a sumptuous white flower. In Asia, the name it is given is, Japanese rose, symbolizing purity and longevity and there are thought to be more than 120 varieties. For Coco, it symbolized love, simplicity, and grace. In Asia, the name symbolizes excellence without pretension. So highly regarded, the camellia was named the national flower of the ancient Kingdom of Dali. Japanese poet, Matsuo Dashõ, wrote a haiku in 1691: Falling upon earth/Pure water spills from the cup/Of the camellia.

Positive/negative camellia motif on a fabric created for Chanel in 1934.

Fabric motif created for Chanel in 1934.

The Camellia japonica, ‘Alba Plena’, one of the oldest varieties, is the example used for Chanel’s flower designs—it’s thought the same variety was given to her by “Boy” Capel. The double pure white ‘Alba Plena’ possesses no scent, nor thorns and is long-lasting. That it lacks fragrance, it would not compete with her perfume, Chanel Nº 5, introduced to the public in 1921.

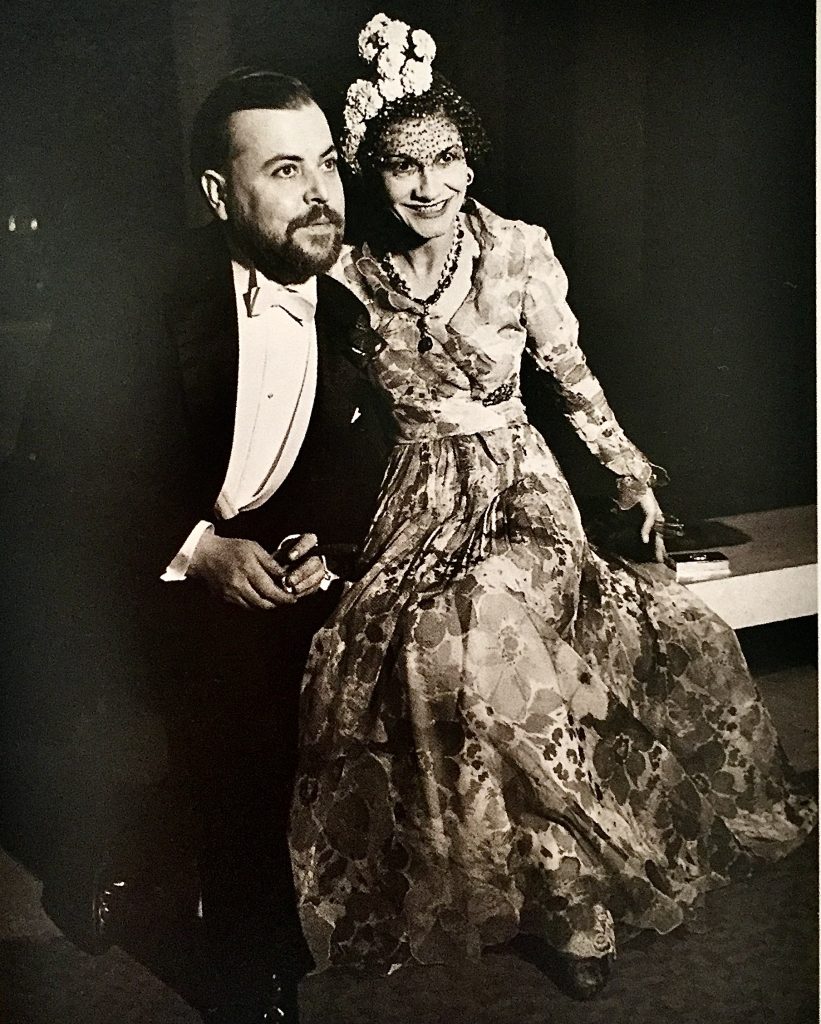

Chanel and Christian Béard in the Italian Pavillion on the day it was inaugurated at the Paris Exposition des Arts et Techniques 1937

Imagine—Chanel in her exquisite Paris apartment, she’s surrounded by her cherished Coromandel screens. Included in the many images carved into the screens are les camélias—stems of the flower amongst the birds. It was she who designed the stunningly beautiful chandelier in her Cambon apartment—adorned with dozens of crystal orbs, stars, grapes, and camellias. The simple flower found itself amongst acanthus leaves in the Venetian crystal chandelier in her office. Camellias were found hanging from other chandeliers and on mirrors. It’s well known that when Chanel found a lucky charm or symbol she surrounded herself with them. Le camélia had entered her private world—a lucky charm that would remain forever special.

Chanel surrounded by her Coromandel screens in 1937. Photo Boris Lipnitzki.

The role of the camellia had taken its place as part of the Chanel style by the 1950s. Bott: “A boater, a suit with gilt buttons, one or more camellias, a gold chain belt, a quilted bag, pale stockings, two-tone pumps: all the iconic features of the timeless Chanel look were firmly in place.”

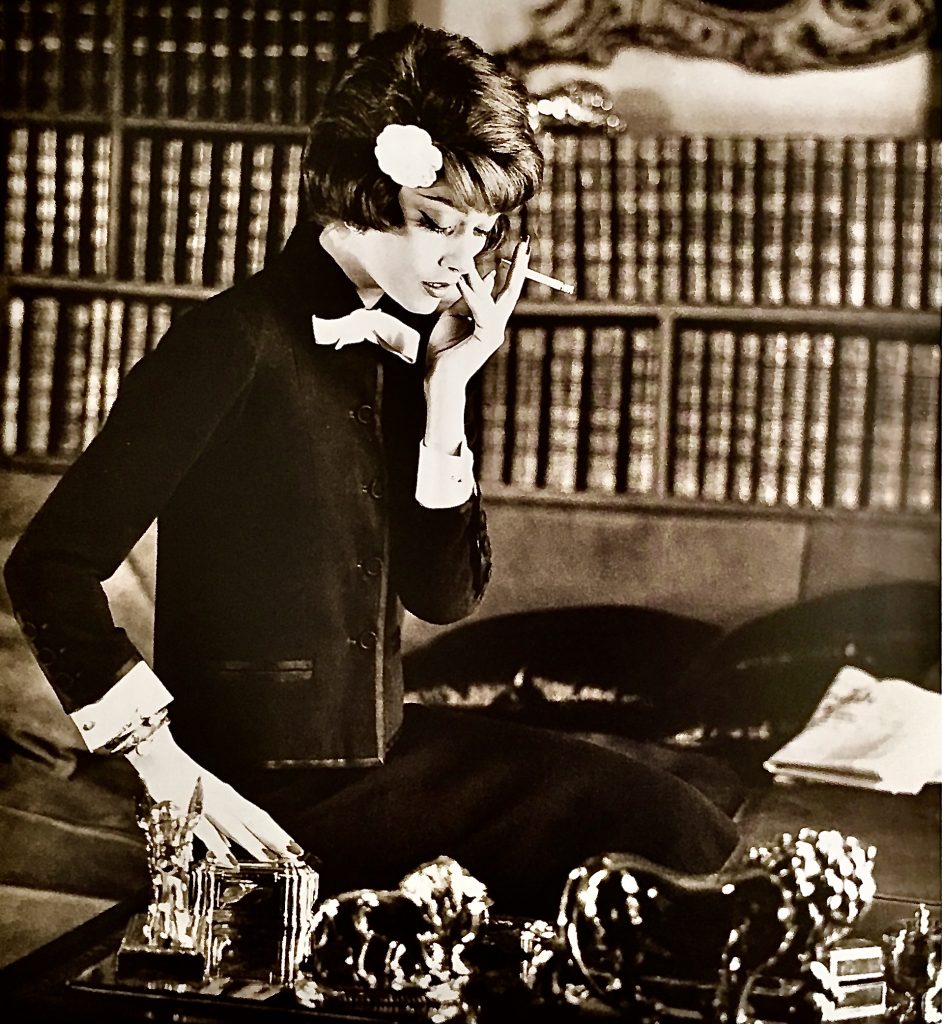

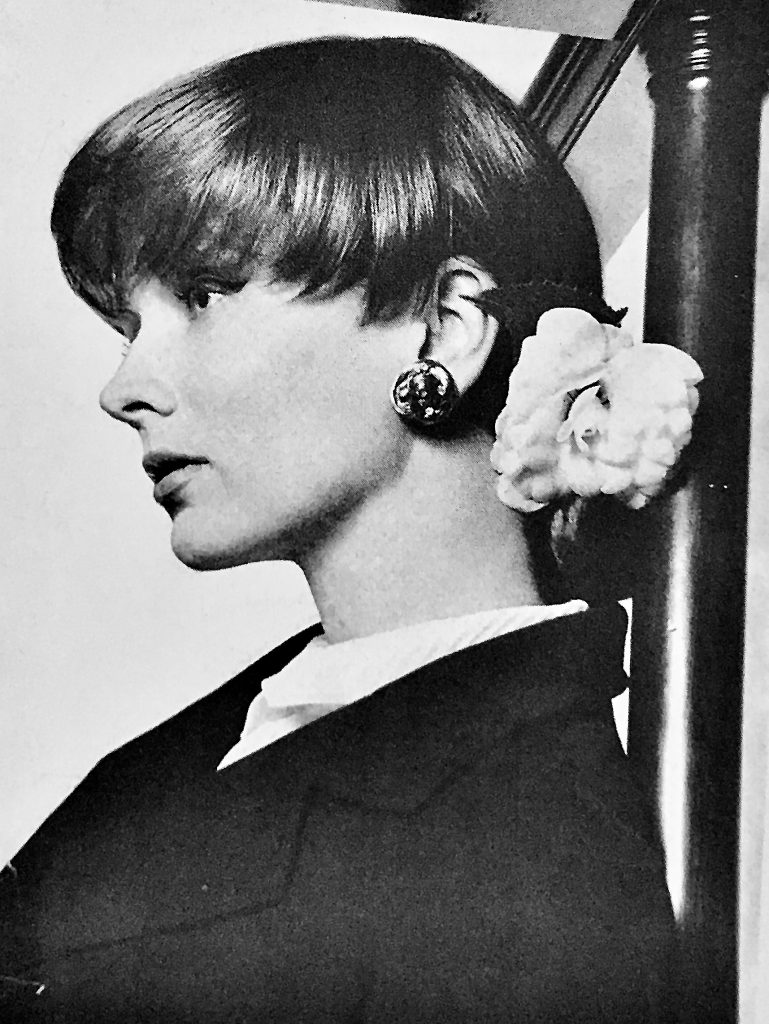

Marie-Hélène Arnaud, said to be one of Chanel’s favorite models, appeared in Marie-Claire, September 1959. From her cropped hair with a camellia, to the black suit with a bow at the neck, turned-up cuffs, depicted the Chanel style. Photo Yurek.

Chanel was photographed in 1965 gazing up at the striking crystal chandelier in her apartment at 31 rue Cambon—donned in a hat, wearing one of her iconic suits (white, with darker piping around the edges), a brooch pinned in the center of a simple silk blouse, earrings, strands of pearls and, if you look closely, two-toned shoes. In the room, are shelves of the books she so loved reading—the Coromandel screens in the room are out of the camera’s range in that picture. Many biographers have mentioned that she wasn’t one to go out at night very often, so I have come away imagining her quietly reading during the evening.

Chanel gazing up at the striking chandelier she designed in her apartment on rue Cambon.

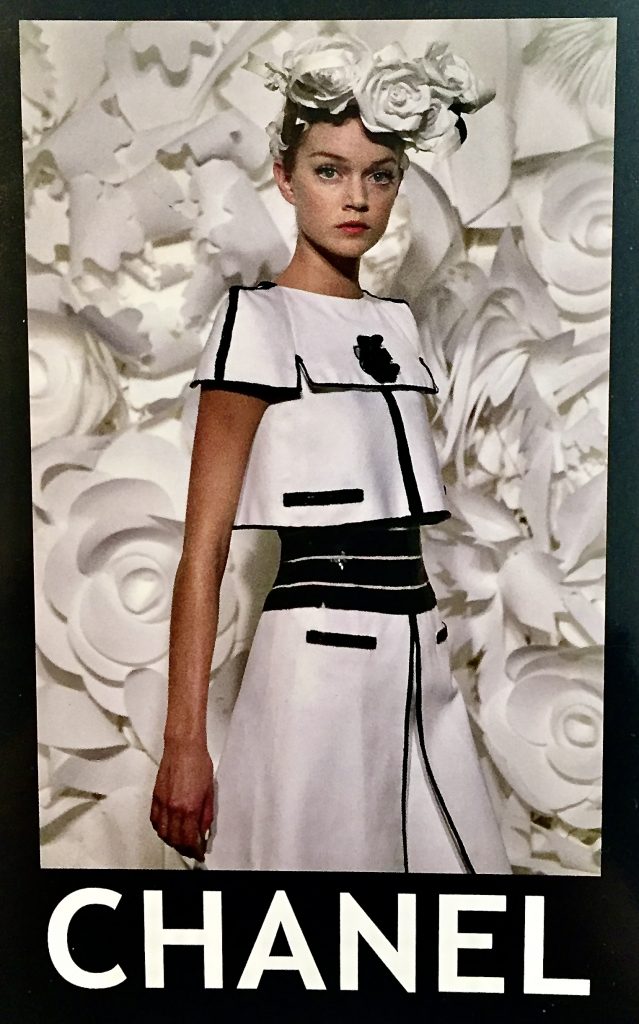

The tradition of the Chanel camellia was carried on by Karl Lagerfeld. The camellia was in every catwalk, always reimagined, designs never repeated from season to season. It’s adorned dresses, head-ware, and jacket lapels. Danièle Bott points out that Lagerfeld considered the camellia a hallmark in design, saying, “an echo of the past revisited, a playful allusion to the house style…the camellia is the spirit of fashion.” He created the camellia in all sorts of fabrics and sizes. Included in the 2005 Autumn-Winter collection was a wedding dress embroidered with 4,000 camellias, taking seven hundred hours to create.

Camellias in black and gold embroidered on a dress. 2005 Spring-Summer Haute-Couture collection. xxxxxxxx

A wedding dress covered in 2,000 camellias was a standout at the 2005 Spring-Summer Haute-Couture collection.

Chanel, by Karl Lagerfeld.

Book cover, by Emma Baxter-Wright. xxxxxxxxxxxxxx

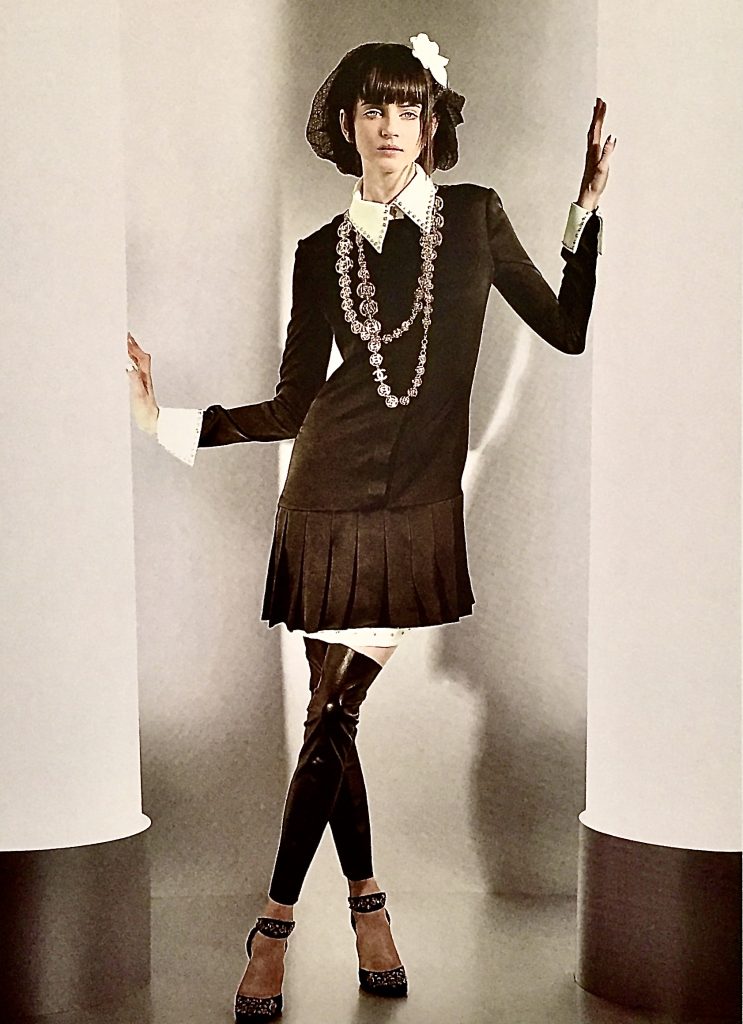

The iconic Chanel camellia worn with a very contemporary ensemble.

Massaro sandals and shoes with camellias embroidered by Lesage (a satellite atelier) for Chanel.

Sequined and embroidered tweed by Lesage for Chanel.

The camellia was printed on the knitted check fabric. 2005 Autumn-Winter Prêt-a-Porter

The Chanel camellia–always reimagined.

Chanel once said: “There are a hundred ways to wear a flower.” Myriad interpretations of the Chanel camellia motif have adorned shoes, handbags, buttons, has been embroidered on or woven into fabrics, encrusted with gems, the camellia motif found its way into the design of bracelets and necklaces. The first piece of jewelry inspired by the camellia was in 1938—a necklace made from translucent glass that was handcrafted in the Gripoix ateliers. The 2013 Chanel Fine Jewelry collection drew inspiration from the camellia blossom—each piece is truly breathtaking!

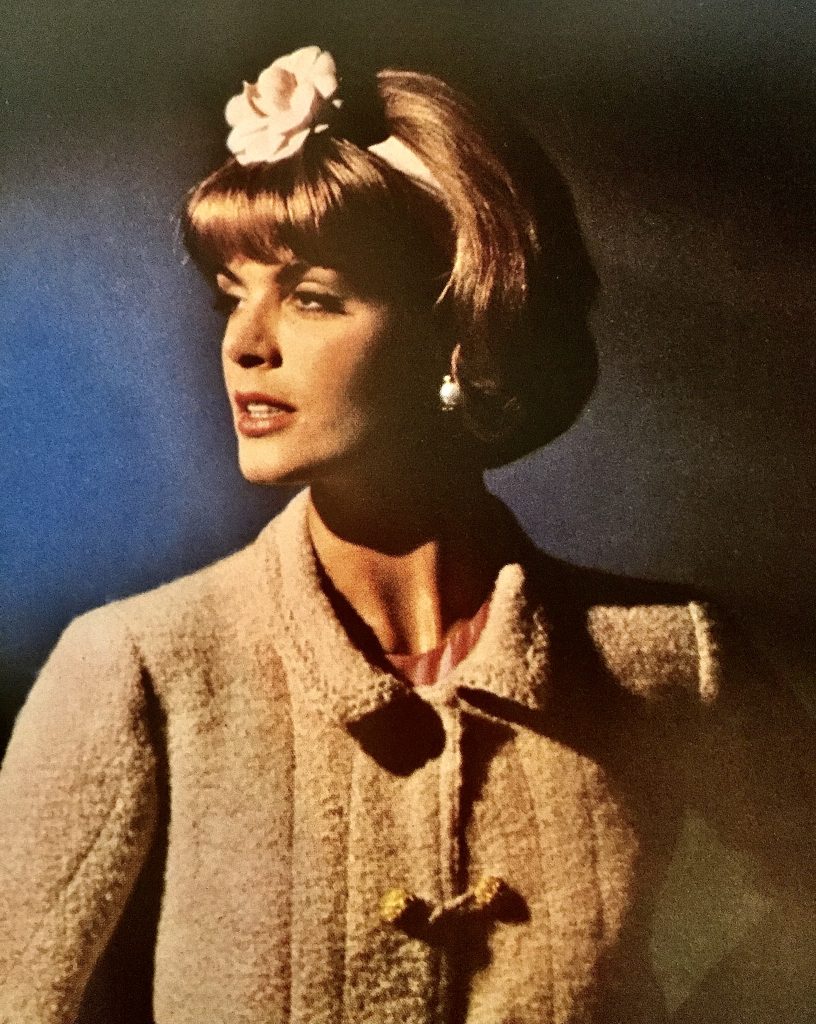

Camellia on a headband was just the right touch with a tailored pale pink suit. Photo David Bailey, Vogue France, September 1963.

Suzy Parker with a camellia in her hair. She is said to have been one of Chanel’s favorite models.

Buttons.

A black and white diamond camellia brooch accenting a five-strand pearl choker. September 2010.

Featherweight chiffon fashioned into a camellia for the 2004 Spring-Summer Haute Couture.

The simplicity and grace of a single, white silk camellia pinned on a blouse, jacket or dress is often just the right touch. Although, adding a strand or two of pearls may very well not be over-accessorizing. I believe Mademoiselle Chanel would approve.

À bitentôt

Quotes and pictures:

Coco Chanel: The Legend and The Life, by Justine Picardie, published by it books, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers.

Chanel and Her World: Friends, Fashion and Fame, by Edmonde Charles-Roux, published by The Vendome Press

Chanel: Her Style and Her Life, by Janet Wallach, published by Doubleday

The Little Book of Chanel, by Emma Baxter-Wright, published by Carlton Books

Chanel’s Riviera, by Anne de Courcy, published by St. Marten’s Press

Chanel: Collections and Creations, by Danièle Bott, published by Thames & Hudson

The Allure of Chanel, by Paul Morand, published by Pushkin Press 2017 Translated from the French by Euan Cameron

The Golden Riviera, by Roderick Cameron, published by Editions Limited