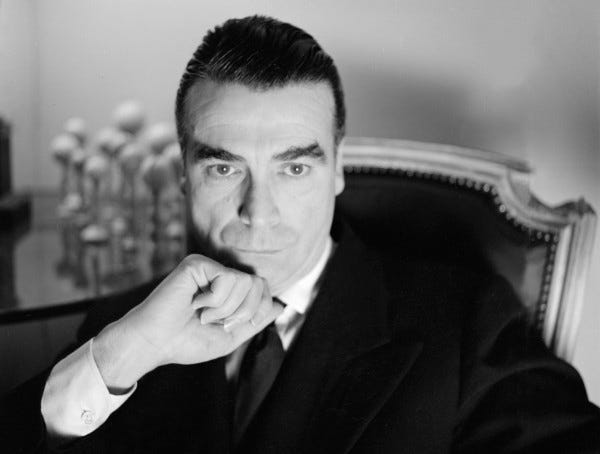

Cristóbal Balenciaga And The Spirit Of The Age

Photograph by Louise Dahl-Wolfe, 1950

“Don’t waste yourself in society” Cristobal Balenciaga once told a fabric designer friend. The private and taciturn Spanish master of haute couture wanted to communicate through the perfectionism of his work, and so to the press and even his own biographers he remains mysterious.

He is still considered by many the greatest couturier who ever lived. Why do certain times and places create such people and why do other moments stifle and destroy them? Reading Mary Blume’s biography The Master Of Us All: Balenciaga, His Workrooms, His World it seems like he was always being thwarted by the violent chaos of history. With all of its sudden pitiless turns, it forced him to move, to transform and ultimately to close it all down, but the height of his work was also made possible by these destructive and uncontrollable forces imposing on him.

He was the son of a fisherman and a seamstress, born in the seaside town of Getaria, Spain in 1895. (Blume wondered if making an impact in the tumultuous time to come required a certain outsider grit, noting that “the three most radical courturiers of the twentieth century -Vionnet, Chanel, and Balenciaga – were the only ones to be born poor.”) It was a noblewoman and patron of the arts, the Marchioness de Casa Torres, that became his earliest supporter and customer, enabling him to develop his craft and establish a studio in San Sebastián in 1919. Many have noted the Spanish influences of the church, the toreador, regional costume and Spanish painting on his work.

Black lace dress and coat with pink belt, 1951. Photo by Henry Clarke/Corbis

At the beginning of the brutal and bloody Spanish civil war in 1936 he left for Paris, the world capital of fashion. Having not long established himself there, then came the German occupation of Paris in 1940. But, Blume wrote:

“the war years made Balenciaga into the great couturier he became. His unusual situation as a Spanish citizen in occupied Paris meant that he could travel to his couture houses in neutral Spain and bring back fabrics that …were better than what was available.”

The American press continued to publish on Balenciaga’s creations via Madrid and most importantly:

The third benefit, and the most crucial to his development as a designer, was, quite simply, the silence of those gray years. Closed off in his studio, which became a sort of laboratory, Balenciaga could work quietly and develop his craft. Until then he had been merely gifted, by the war’s end he was unique.

Balenciaga cultivated a unique aesthetic, forbidding the display of merchandise, Blume writes, and instead had mythical sculptures on display – with names like La Parfumeur, Le Couturier, or La Modiste, and The Tower of Babel.

He kept his personal life private but after his partner Wladzio d’Attainville died in 1948, he created an all black collection of mourning.

Photo by Richard Avedon, 1950

Because of the unique international style he developed during this time and its percieved detachment from the Paris scene, the post-war period put Balenciaga in another strange position. Under the anti-Americanism and spirit of French chauvanism of the DeGualle years, his international style was described as a “closed universe” of influence.

Photo Irving Penn for Vogue 1950

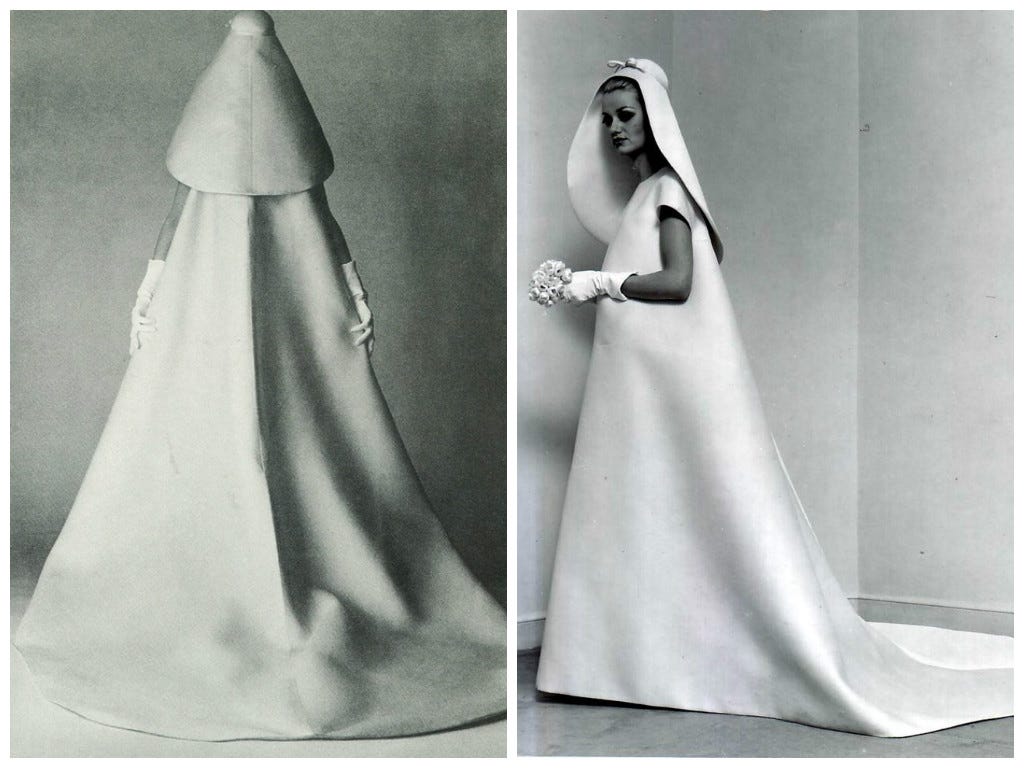

Cristobal Balenciaga, Wedding Dress and Hat, 1967

Then the times brought the decline of Spanish cultural prestige. Blume writes:

“Spain, fashionable in France from the days of Empress Eugenie through Salvador Dali, was seen in the dwindling Franco days of the 1960s as a poor and backward country, a cheap supplier of domestic help and not a source of the new.”

The final turn came with the spirit of the 60s – plastic, miniskirts, the “youth quake”, the rise of swinging London and Mary Quant. Blume writes that Brigitte Bardot’s arrival announced that haute couture was for grandmas. His style’s solemnity, worn by older women of distinction, was replaced by ready-to-wear mass produced style which fitted the giddiness, partying and youthful energy of the cultural revolution underway.

Then came the riots of Paris in May ‘68 which Balenciaga perceived as “the end of the world.” Blume writes, “the dramatic photos of the May events in Paris – the burning cars, the street fighting – seemed a replay of Spain’s chaotic civil war: a sign or a pretext, to close.” Without warning, he closed his doors in Paris. The New York Times reported “Nothing left to achieve, Balenciaga calls it a day.” Givenchy said “He left like the grand seigneur he was. He closed the door.”

In retirement in Spain his friend Claudia Heard de Osbourne said he looked good and would come out to dinner but “he and I would always cry, though, before the evening was over.”

When he died of heart failure, no will was found but he had reportedly told friends that he wanted his brand name to die with him. But the family decided otherwise and the name has been bought and sold and passed through various owners ever since.

Throughout all of his creative years he remained an observant Catholic. In Paris, Blume writes, he had “walked daily up the Avenue Marceau to his parish church, Saint Pierre de Chaillot” where he made the cassock for the priest, Father Pieplu, who delivered his funeral eulogy in 1972. He said that to Balenciaga, “his work revealed god’s hidden harmony”.