How Spanish Painting Influenced Cristóbal Balenciaga

Mục lục

A new exhibition in Madrid brings 90 pieces of Balenciaga couture together with 56 masterpieces of Spanish painting that inspired the designer – here, we explore how Spanish art shaped

his work

Text

Agnish Ray

When a 41-year-old Cristóbal Balenciaga moved to Paris in 1936, he began to miss his native Spain. Suddenly displaced from home, amid the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, and plunged into the beating heart of Europe’s high fashion scene, he searched for inspiration by delving into memories of his childhood in the small town of Getaria in the Basque Country, much of which he spent in the company of his mother – herself a seamstress – and her aristocratic clients. Encountering these clients’ splendid art collections as a young boy sparked a lifelong fascination with old master painting – a passion that produced the billowing shapes, voluminous architecture, minimalist lines and bold colours that came to define Balenciaga’s craft.

Balenciaga’s A/W19 collection is full of chunky silhouettes, slouchy shoulders and trim trouser lines. But the fashion house today, directed by Demna Gvasalia, presents a very different aesthetic to what Balenciaga himself was making during his lifetime. “It’s impossible to compare them,” explains Eloy Martínez de la Pera, curator of a new exhibition Balenciaga and Spanish Painting in Madrid which brings 90 pieces of Balenciaga couture together with 56 masterpieces of Spanish painting that inspired the designer. “The narrative of Balenciaga ended when he stopped making clothes. His storytelling was tremendously personal – the Balenciaga of today has a totally different story to tell.” And in order to really get to know Balenciaga himself, it is important to know the key elements of Spanish art that sewed together his aesthetic vision.

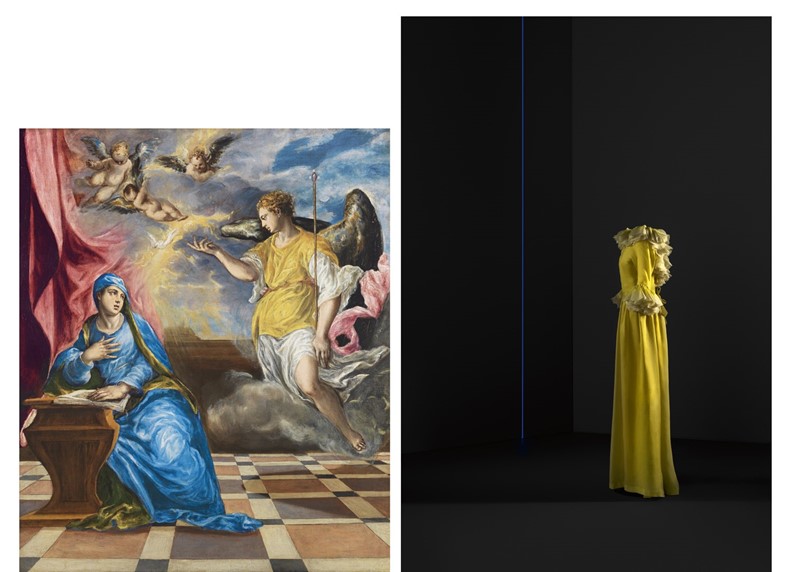

El Greco – colour

A powdery pink satin evening gown sits alongside a bodice-jacket-skirt ensemble made of crisp red taffeta. You might never imagine that these pieces of 1960s couture were inspired by the Virgin Mary – but once they are set against El Greco’s monumental paintings of the annunciation, it is impossible not to compare the vivid hues of the Virgin’s billowing robes with the sumptuous tones of Balenciaga’s dresses. Similarly, the colour of the archangel Gabriel’s heavenly garb echoes in Balenciaga’s elegant mustard satin evening gown (1960) and jaunty yellow silk dress with a feathered evening cape (1967). El Greco’s vibrant use of colour penetrated Balenciaga’s imagination when he encountered the artist in the palace of the Marquesa of Casa Torres (one of his mother’s most important clients), coming to form a central component of the iridescent pieces Balenciaga produced in Paris in the 40s and 50s.

Right: Evening gown (silk organza) 1968. Colección de Dominique Sirop, Paris. ©

Jon Cazenave.

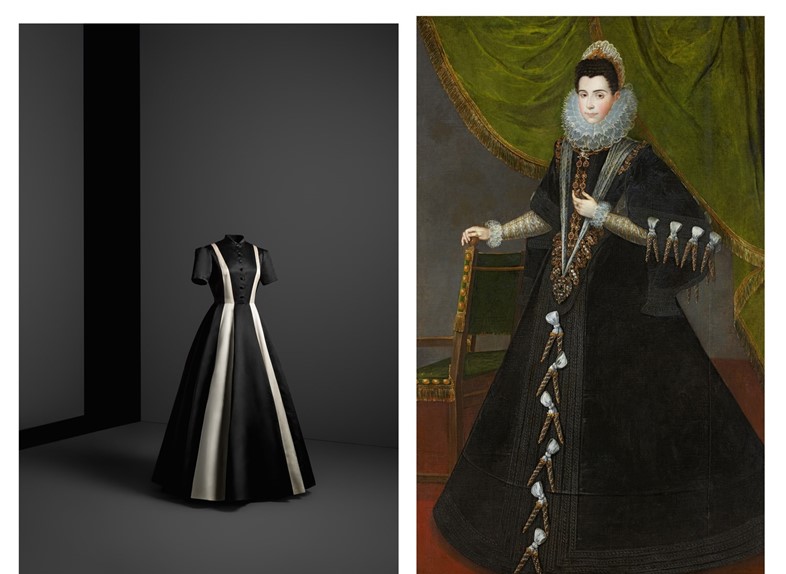

Court painting – black

If it was vivid greens, yellows, blues and pinks that Balenciaga took from El Greco, then in Spanish court painting of the late 16th to mid-17th centuries he discovered his love of the colour black. Balenciaga was a deeply religious man himself – so he found nothing but beauty and inspiration in the austere solemnity of figures shrouded in dark, holy habits. It’s easy to see how, on seeing majestic court portraits like Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo’s of Princess Margaret Theresa (1665–1666), or that of Queen Elisabeth of Valois by Juan Pantoja de la Cruz (1605), Balenciaga was hooked on black. However, in true Balenciaga style, the pieces that emerged in the late 50s – like his little black cocktail dresses and feathery sequined shoulder capes – were a thrilling, almost unholy, twist on a courtly classic.

Right: Anonimo Español del Siglo XVII, ‘Portrait of the VI Countess of Miranda.’ Fundación Casa de Alba. Palacio de

Liria, Madrid.

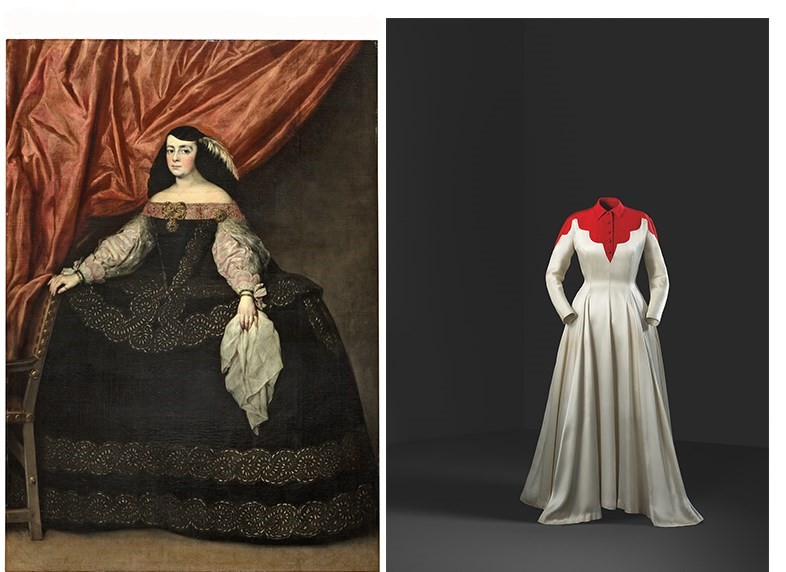

Velázquez – shape

In Las Meninas (1656) by Velázquez, one of Spain’s most important artworks, the five-year-old Margaret Theresa, known as the infanta of the royal court, is tended to by her ladies-in-waiting. The painting immortalised the figure of the young princess in her box-like panniered skirt, extended widely around her body, torso bound tight. A similar dress shape is found in Juan Carreño de Miranda’s portrait of Doña María de Vera y Gasca (1660-1670). This distinctive silhouette inspired Balenciaga’s Infanta dress, which he designed in 1939. His modern reinterpretation of the Velázquezian shape had a narrower skirt and less exaggerated shape overall. But the cut was unquestionably an homage to the 17th-century painter – and it formed the basis of many of the Balenciaga silhouettes that would follow, from the balcony skirt to the baby doll dress.

Right: Infanta dress, 1939 Gros de Tours and satin Museo

del Traje

Zurbarán – volume

During World War II, fabric for women’s clothes was largely restricted in Europe, reserved for military use instead. So Balenciaga was part of a post-War boom in exuberant fabric use – evident in the heavy volume and layered materials of his dresses. Curator Martínez de la Pera describes Francisco de Zurbarán – primarily known for his religious paintings – as “the first fashion stylist of art history”. In his portraits of Santa Casilda (1630-1635) and Santa Isabel de Portugal (1635) he whimsically depicts saintly figures in outfits that today might look fit for a runway. While the paintings depict scenes of charity and godliness, what struck Balenciaga was the thick layering of the skirts, piously (yet playfully) clutched in the women’s hands. Meanwhile, the voluminous creamy white robes of Zurbarán’s monks paved the way for the lustrous ivory wedding dresses that Balenciaga tailored for the likes of Queen Fabiola of Belgium and Carmen Martínez Bordiú (Franco’s granddaughter).

Right: Francisco de Zurbarán, ‘Saint Elisabeth of Portugal’ circa 1635. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid. © Archivo Fotográfico Museo Nacional

del Prado.

Goya – material

Bettina Ballard, editor of Vogue in the 50s, once said: “Goya, whether Balenciaga is aware of it or not, is always looking over his shoulder”. The artist’s portraits of the Duchess of Alba (1795) and the Marquesa of Lazán (1804) depict the translucent lace trimmings of the women’s white dresses. This seductive sensation of lace bowled Balenciaga over. Goya’s ability to represent the transparency of fabrics made him strive for lace, tulles and silks delicate enough to conceal and reveal at once – materials which appeared on several dresses he produced in Paris. It may also have been Goya that encouraged Balenciaga’s skill for breaking a flowing shape with a sudden strong line – just how the Duchess of Alba’s delicate white gown is interrupted by a bright red bow tied tightly around her waist.

Right: Francisco de Goya, ‘Queen María Luisa in a Dress with hooped Skirt’ circa 1789 Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid. © Archivo Fotográfico Museo Nacional

del Prado.

Balenciaga and Spanish Painting is on at Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid until 22 September 2019.