Quality of Space, Culture and Trigonometry Art – MAHB

Mục lục

Quality of space: shapes, lighting, and temperature

The room from which you are observing the window or wall is just a fraction of the number of rooms in the building or the number of rooms in a city or the number of rooms in the world. You may not recognize the rectangular box as a repeating global pattern yet rectangular spaces have become the global hallmark of building construction efficiency (Steadman, 2006). Repeating shapes that can change in size without changing shape (e.g. rectangular rooms and buildings) are known in mathematics as fractals (Eglash,1999). You played with fractals as a child when you unknowingly used trigonometry (a form of mathematics commonly used in architecture), to draw overlapping spirals (ArtJohn, 2019, ThinkTVPBS, 2014). Trigonometry is useful for analyzing geometric shapes and distance ratios. The function of buildings can be examined from the perspective of trigonometric shapes.

An interesting question that emerges is: does the shape of a building affect the distribution of natural light, ventilation, and temperature? The answer is yes. Pathirana, Rodrigo, and Halwatura (2019) found that when comparing rectangular, square, and L-shaped buildings, a rectangular building with a staircase in the middle offers the optimal comfort zone parameters in a tropical climate. Whether or not the residential property you occupy has a staircase in the middle, chances are high that the building shape and the surrounding plot have a rectangular shape. The shape of our buildings also affects the shape of our land-use patterns.

Quality of space: cultural heritage, communal spaces, and knowledge transfer

The main purpose of residential architecture is arguably to manage the clutter of personal belongings as well as to integrate the socio-economic aspirations of the homeowner and the surrounding neighborhoods. However, what can we learn from examining the residential architecture of cultural groups with a preference for round instead of rectangular stacking shapes?

Nubian architecture

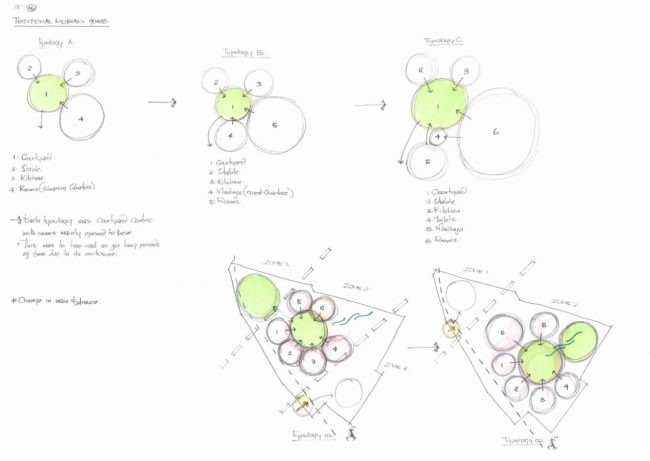

Traditional Nubian architecture was divided into three main typologies. The difference between the three ethnic Nubian architectural typologies is the spatial arrangement related to their sizes. The typical Nubian house is very spacious with several large rooms that accommodate extended family members and guests (Asmail, n.d.; Maina 2019). As in ancient roman architecture, the Nubian home has an open atrium which was used as a gathering space for meals and socialization. The front of the house was covered in colorfully painted geometric patterns with religious connotations. These colors are an admired and distinctive feature of the Nubian culture. The Nubians did not rely on any engineers or architects, however, their architecture was geometric in form and retained an ancient technique for roofing in mud brick.

The hierarchical order of how the spaces are arranged is culturally linked to their heritage and was set at irregular intervals in a staggered line somewhat parallel to the river Nile. Their principal entrance to the houses always faced the rivers whether they were on the east or west banks, it didn’t matter but the direction towards the river was important. The main entrance led into an open courtyard with palm stems and branches that covered the entrance to the adjacent rooms that made up the exterior wall perimeter of the house and acted as a covered seating area alongside the courtyard. This covered seating space around the courtyard created the opportunity for people to interact with one another regularly. It is, for this reason, the proposed design implements such culturally linked ideas.

Each typology had a guest room or Mandura which had a separate entrance allowing the freedom of movement while maintaining family privacy in the inner quarters. The Mandura was considered an important part of the house since the Nubians believed in the significance of hospitality which continues to be an important obligation (Asmail, n.d.) to this day. The larger houses had separate entrances for animals and people but both had to walk through the courtyard. Depending on the width of the yard enclosure (Mahmoud Bayoumi, 2018), the courtyards trapped cool air for a long time. Like the proposed design, the courtyard played a key role in trapping the air and acted as a connecting space to the classrooms around it. The construction materials were sourced locally to minimize cost and to maintain a sustainable way of building. The walls were made of mud, mud-brick, or stone and for their roofs they used split palm trunks and acacia wood beams. The interior and exterior decorations were plastered on by the women and children of the household. This was a family experience of building homes that created a sense of ownership and cultural significance.

The Kikuyu and Luo architecture

Like the Nubians, the Kikuyu and the Luo communities built their homes together as a way of transferring knowledge from generation to generation, thus maintaining the traditional way of living over time. These traditional practices have not changed much in the era of modernization.

Both cultures largely lived in homesteads of 10 to 14 units per stead depending on the number of extended family members. In the case of the Luo, the number of sons had an impact on the number of units as each son had his own hut whereas the Kikuyu had their sons share a hut or two. A hierarchical order in the placement of the huts was very important with the man’s hut being a focus of most if not all spaces. While the Nubians had their entrances facing the river Nile, the Luo and the Kikuyu had their huts entrances directed towards the man’s hut as a reference point.