Standard of Living in the Developing World

The content on this page has not been recently updated. This content is likely to be no longer fully accurate, both with respect to the research it presents and with respect to what it implies about our views and positions.

This page surveys information about quality of life in the developing world. The purpose is primarily to answer the question, “If a donor’s funds save a live, what sort of life is saved?”

We make no attempt to fully convey what life is like; instead, we focus on what facts are available from relatively broad, large-sample, plausibly representative studies. We restrict ourselves to basic questions such as “What health problems are common and how common are they?”, or “What problems do people in the developing world generally list as particularly important?”

For someone seeking a more qualitative (and less representative) picture, we suggest a visit to the developing world.

Mục lục

Summary

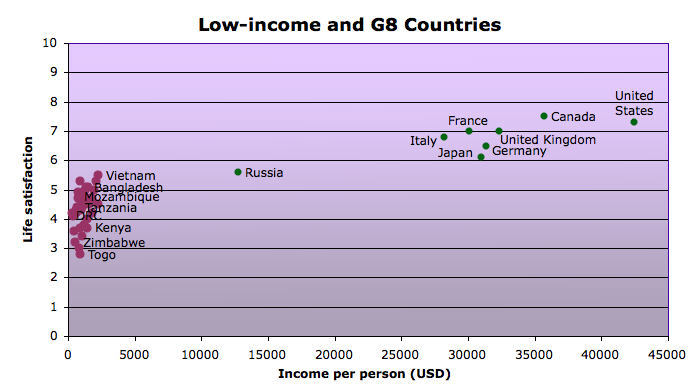

- Self-reported life satisfaction: People in poor countries report that they are on average less satisfied with their lives than people in rich countries. The average resident of a low-income country rated their satisfaction as 4.3 using a subjective 1-10 scale, while the average was 6.7 among residents of G8 countries. We interpret this as a large satisfaction gap.

- Incomes: A large proportion of the population in developing countries live on under $1 or $2 per day. The poor spend a large proportion of their incomes on food, may lack access to basic infrastructure, and own few productive assets. However, they do make consumption choices that involve spending on things other than food and use a variety of instruments to manage erratic income streams. Ownership of televisions and radios and access to electricity and sanitation varies widely.

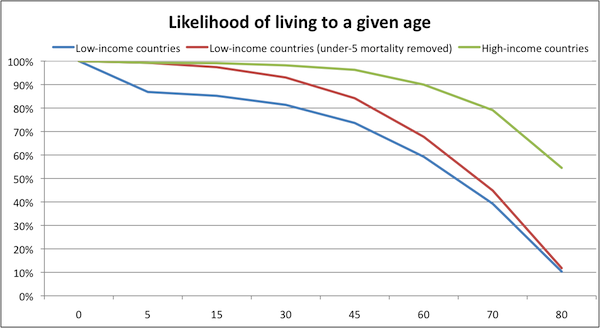

- Mortality: On one hand, people in Sub-Saharan Africa are much worse off, and much more likely to die prematurely, than people in wealthier parts of the world. On the other hand, those who live past the age of 5 have strong chances of living to age 60 or so; saving a life even from a single cause of death means saving a person who is likely to live quite a while longer.

- Morbidity: A third of children under five in developing countries show evidence of long-term malnutrition. Malnutrition can cause low energy, diarrhea, anemia, hypothyroidism, poor vision, and pneumonia, as well as increased susceptibility to many other diseases. Prevalence of parasitic worm infection is very high in many poor regions. Malaria causes frequent sickness among children under 5, who average over 4 days of sickness with the disease per year.

- Development Priorities: Sub-Saharan Africans rank reducing poverty and hunger as the two most pressing Millennium Development Goals. Health goals are also prioritized.

Income and self-reported well-being

Are people in poor countries less satisfied with their lives?

The Gallup World Poll asks a representative sample of people from 132 countries to answer questions about their well-being. Examples include asking respondents to rank their life satisfaction on a scale from 0 to 10 and to answer the question “are you satisfied or dissatisfied with your personal health?” This data has been used to look at the relationship between level of economic development (income, health status, etc.) and self-reported well-being.

The 2006 Gallup World Poll data shows a positive correlation between per capita income in a country and average self-reported life satisfaction. One report on the World Poll data concluded, “high-income countries have greater life satisfaction than low-income countries…there is no evidence that the cross-country effects of greater income fade out or vanish as countries increase their income.”

In the chart below, average life satisfaction (as measured by the Gallup World Poll) is plotted against income for the 38 of the 43 low-income economies (as classified by the World Bank)

for which World Poll data is available, as well as for the members of the G8.

Relatively high-income countries report satisfaction levels between 6 and 8 (on a scale from 0 to 10); low-income countries report satisfaction levels between 3 and 5.5.

The difference between satisfaction in the average low-income country and the average G8 country is about 2.4, or a little less than a quarter of the scale (which ranges from 0 to 10, with 0 representing the worst possible life and 10 representing the best possible life).

Income and assets

Global poverty rates

Poverty rates have been decreasing in many parts of the world, but the number of people living below the international poverty line remains high, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Data on the number of people living on less than $1.25 per day (the international standard of extreme poverty)

and on less than $2.00 per day (another international poverty benchmark) is based on dissimilar national studies from a limited number of countries,

and thus should be approached with caution. Recent World Bank data estimates the number of people living on under $1.25 a day at about 1.4 billion worldwide.

About half of Sub-Saharan Africans live on under $1.25 a day.

Many more live just above this line. Over 2.5 billion people live on less than $2 a day, with nearly three-quarters of the population of Sub-Saharan Africa falling into this category.

(Note: These figures are calculated for purchasing power parity (PPP), meaning that someone earning “$2 a day” does not literally earn this much but the equivalent of what 2 U.S. dollars could buy in the United States.

)

What does it mean to live on under 1 or 2 dollars per day?

Most of the points below are taken from analysis by Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo of survey data from 13 countries.

We also consider information from Portfolios of the Poor,

which tracked the financial lives of over 250 households in 3 countries at a high level of detail.

- Most of income is spent on food. People living on less than $1 or $2 per day reported spending a large proportion (between 55 and 80%) of their incomes on food. The proportion of income spent on food was not substantially different between the under $1 and under $2 per day groups.

- There is little ownership of “productive assets.” People living on under $1 a day generally reported owning few “productive” assets such as bicycles, sewing machines, phones, or tractors,

though in some areas a large proportion of poor households own small plots of land. - Varying ownership of TV and radios. Ownership of non-productive assets also varied widely across countries and between urban and rural areas. In Tanzania, for example, almost no one living on under $1 a day reported owning a television, while 57% of those living on the same (adjusted) income in Hyderabad, India owned one. Rates of radio ownership were higher than those for television. About 70% of those living on under $1 a day in Peru, South Africa, and Nicaragua own radios, and in several other places ownership rates were over 40%.

- Varying access to electricity, water and sanitation. The poor often lacked access to basic infrastructure, and as with assets, there was large variability among households around the world. In Mexico and Indonesia, for example, electricity access was nearly universal, but in-house tap water and ownership of a toilet or latrine were far less prevalent in Indonesia (data for Mexico not available). In Tanzania, the pattern was quite different: nearly every poor household owned a toilet and very few had access to electricity or in-house tap water.

A poor urban community in Cape Town, South Africa with access to electricity but without household latrines or in-house tap water.

- Poor health. The poor reported often being sick. Among the surveys cited by Banerjee and Duflo (2006), no surveys yielded an average ‘percent of household members sick’ (in the month before the survey) of below 10%, and many reported rates above 25%.

- Multiple occupations. Banerjee and Duflo (2006) also looked into how the poor earn their incomes. One pattern they found in many parts of the world was the tendency of the poor to engage in multiple occupations. Common occupations were running very small businesses, small-plot agriculture, and day labor.

The authors argue that by spreading themselves across a variety of occupations and operating their businesses at such small scales, the poor miss out on gains from specialization and scale economies.

They believe that this poverty-perpetuating behavior comes from the desire of the poor to minimize risk as well as their inability to raise the capital needed to operate more efficiently. - Unpredictability and risk. Banerjee and Duflo (2007) argue that what often separates the ‘middle class’ (which they define as living on between $2 and $10 per day) from the poor in developing countries are steady well-paying jobs, not greater success at running small businesses.

Banerjee and Duflo hypothesize that more reliable income flows may be the reason the middle class invest more of their income in the future than the poor do.

(However, we note that it is also possible that, to some degree, people who are more future-oriented in general are the same people who end up with higher incomes.)Portfolios of the Poor suggests that in addition to having small incomes, the poor often have irregular and unpredictable incomes.

The book reports on Collins, et al.’s studies of how the poor in India, Bangladesh, and South Africa manage the fact that “the reality of living on two dollars a day is that you don’t literally earn that sum each day.”

Mortality and Morbidity: what are the major health problems in the developing world?

On one hand, people in low-income countries are much worse off, and much more likely to die prematurely, than people in wealthier parts of the world. On the other hand, it’s important to note that those who live past age 5 have strong chances of living to age ~60; saving a life from even a single cause of death means saving a person who is likely to live significantly longer.

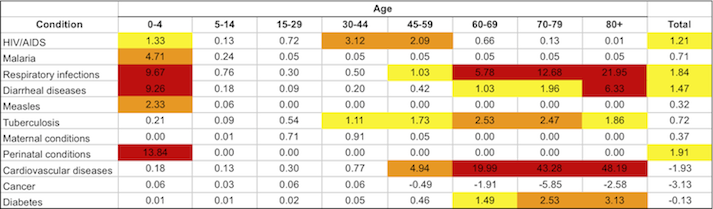

Children under 5 in low-income countries primarily die of preventable and treatable diseases such as malaria, respiratory infections, diarrhea, perinatal conditions, measles, and HIV/AIDS. Between ages 5 and 60, the major causes of death in low-income countries (relative to higher-income countries) are HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and maternal mortality (i.e., deaths in childbirth). After age 60, there are large differences in the mortality rates for many of the same causes of death that affect those under 5, as well as for many conditions that require advanced medical attention (heart disease, cancer, diabetes).

The table below shows the differences between low-income and high-income countries, in terms of deaths per 1,000, by age range and cause of death. It is color-coded: yellow squares represent causes of death for which mortality rates are greater in low-income countries by at least 0.5 deaths per 1,000 people, orange squares represent causes of death for which mortality rates are greater in low-income countries by at least 1 deaths per 1,000 people), and red squares represent causes of death for which mortality rates are greater in low-income countries by at least 2.5 deaths per 1,000 people.

Note that conditions vary within the developing world. Mortality rates for many causes are higher in Sub-Saharan Africa than in the group of low-income countries (which includes some highly populous Asian countries, such as India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh). For more information, see our discussion of life expectancy in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Non-fatal health problems

Household surveys of those living on under $1 or $2 per day show that the poor are often sick. In the surveys cited by Banerjee and Duflo (2006), in every country for which data was available an average of over 10% of households reported at least one member needed to see a doctor in the month prior to the survey. In many areas the average exceeded 25%; parts of India, Mexico, and Nicaragua had averages above 35%.

Here we do not discuss all health problems in detail, but we present three prevalent conditions (malnutrition, parasitic worms, and malaria) which are both direct causes of symptoms and risk factors for other conditions. In addition, we present data on the prevalence of a selection of health problems that are common in low-income countries and compare prevalence rates in these countries to rates in high-income countries.

Malnutrition is a widespread problem in the developing world. It is estimated that in 2000-2002, over 800 million people in the developing world were undernourished (insufficient energy intake),

and 2 billion are micronutrient deficient.

In 2005, approximately 32% of children under five in developing countries were stunted (had a height-for age that was more than two standard deviations below the global average), which likely reflects chronic undernutrition throughout life.

Malnourishment may be both caused by disease (such as parasitic worms) and increase susceptibility to disease.

Lacking certain nutrients has been associated with a wide range of health problems including low energy, diarrhea, anemia, hypothyroidism, poor vision, and pneumonia.

We do not know how common or severe these symptoms generally are among malnourished people.

Malnutrition is sometimes associated with infection with parasitic worms.

It is estimated that there are more than 1.2 billion roundworm infections globally, ~700-800 million infections with each hookworm and whipworm, and 250 million infections with schistosomiasis.

While most infections do not cause symptoms,

heavy worm infection can cause anemia, dysentery, and growth retardation.

In the long run, worm infection “impair[s] physical and mental growth in childhood, thwart[s] educational advancement, and hinder[s] economic development.”

Death from worm infection can occur, but is fairly rare.

(More on specific types of infections at our discussion of schistosomiasis and our discussion of soil-transmitted helminths.)

Another major cause of disability and suffering is malaria. The Disease Control Priorities Project estimates that there were 213 million cases of malaria in 2000, resulting in over 1.1 million deaths.

This means that while malaria is a leading cause of death, the vast majority of cases are not fatal, but do cause suffering and disability. Like many other diseases, risk of malaria infection and complications are increased by malnutrition.

As can be seen in the chart here, children under five average over 4 days of sickness with malaria per year, and older children fall sick every 2-3 years for an average of 2.3 days. Uncomplicated malaria is characterized by fever, headaches, and nausea.

Severe malaria can cause cognitive impairment, seizures, coma, respiratory distress, and heart problems.

Other conditions. The table below compares prevalence rates for a selection of additional common causes of morbidity in low-income countries. Prevalence rates in high-income countries and for HIV/AIDS are included for comparison purposes.

While prevalence rates are generally higher in low-income than in high-income countries (except for asthma and hearing loss), these conditions, aside from anemia and schistosomiasis, are rare across low-income countries. For many of the infectious conditions, endemic areas may exist where large proportions of the population suffer from the disease, but the average person in the developing world is unlikely to be suffering from these diseases.

% affected in low-income countries

% affected in high income countries

Who is affected?

Anemia

27.9%

5.8%

Mostly women and young children.

Schistosomiasis

9.4%

0.1%

Primarily affects the poor.

Vision impairment

5.0%

3.3%

Primarily affects those over 40. Higher prevalence in poor areas.

Asthma

3.2%

5.2%

Hearing loss

3.6%

6.4%

About a quarter of severe cases affect children.

Lymphatic filariasis

2.5%

0.0%

Prevalence increases with age. Disproportionately affects the poor.

HIV/AIDS

0.8%

0.2%

Primarily affects adults. About 8% of HIV infections are among children.

Vitamin A deficiency

0.7%

0.0%

More likely to affect the poor as it results from lack of meat product, fruit and vegetable, and fat consumption.

Trachoma

0.2%

0.0%

Primarily affects young children and adult women.

Onchocerciasis

1 in 2,700

0.0%

Intensity increases with age.

What problems do people in the developing world believe are most pressing?

In 2006, the Gallup World Poll asked a representative sample from 26 Sub-Saharan Africa countries to rank the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in order of importance to them.

The MDGs are a set of targets established by the United Nations in 2000 on a range of human development goals including poverty, education, health, gender equality, and the environment.

Respondents consistently ranked reducing poverty and reducing hunger as the two most important goals.

Health goals followed the top two, with ‘Reducing the spread of HIV’ ranking third and reducing under five mortality, maternal mortality and ‘Reducing the spread of malaria and TB’ coming in at 5, 6, and 8, respectively, out of a total of 12 goals. One argument for why health goals are not ranked higher than they are, argued by Deaton (2008), is that Africans report being more satisfied with their health than we might expect because they are more used to being sick.

The youth-focused goals of ‘Providing more jobs for youths’ and ‘Achieving primary education for all’ were also considered important by many respondents and were ranked 4 and 7, respectively. The goals of improving access to clean water and sanitation, achieving gender equality, and increasing access to new technology were least important to those surveyed.

Each respondent was asked to rank order six of the twelve goals. A value of 1 was assigned to the top-ranked goal, through 6 for the lowest-ranked goal. Thus the averages below fall in the range of 1 to 6.

Millennium Development Goal

Weighted Average Score

Reducing poverty

2.41

Reducing hunger

2.48

Reducing the spread of HIV/AIDS

3.05

Providing more jobs for youth

3.17

Reducing the death rate among children under five

3.34

Reducing the number of women dying during childbirth

3.38

Achieving primary education for all

3.62

Reducing the spread of malaria and TB

3.64

Improving access to safe drinking water

3.75

Improving access to sanitation facilities

4.09

Achieving gender equality and empowering women

4.38

Providing access to new technology

4.65

There were few differences in how men and women, urban and rural dwellers, employed and unemployed adults, or different age and education cohorts ranked the goals.

Rankings did vary across countries and regions, but reducing hunger and poverty were the top two goals for all but 6 of the 26 countries polled. Of these six, four were Southern African countries where HIV prevalence is very high; all four ranked ‘Reducing the spread of HIV’ as their top priority. Kenya and Uganda also ranked this goal in their top two. Larger differences between countries were seen in rankings of lower priority goals.