The Artistic Inspiration of Balenciaga

Mục lục

Cristóbal Balenciaga was the “Master of us all,” as Christian Dior said, and a “couturier in the truest sense of the word,” according to Coco Chanel. The world was devasted when he passed away in 1972. He was an enigmatic figure who prefered to stay away from the spotlight. He redefined the concept of haute couture and made everyone delirious with his innovative designs. On the occasion of the past exhibition at the Museo Nacional Thyssen – Bornemisza, let’s take a look at the artistic inspiration of Balenciaga.

Cristóbal Balenciaga was a special figure in the fashion world. He designed his first gown at the age of 12. He soon excelled as a couturier for the royalty and aristocracy of Spain. However, at this early stage, there wasn’t any reference to Spanish art whatsoever. After the beginning of the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) and General Franco’s dictatorship, Balenciaga moved to Paris. It was then that he expressed a nostalgia for his mother country. He thus started incorporating references from Spanish art into his designs. There are 8 major references to Spanish art in the artistic inspiration of Balenciaga:

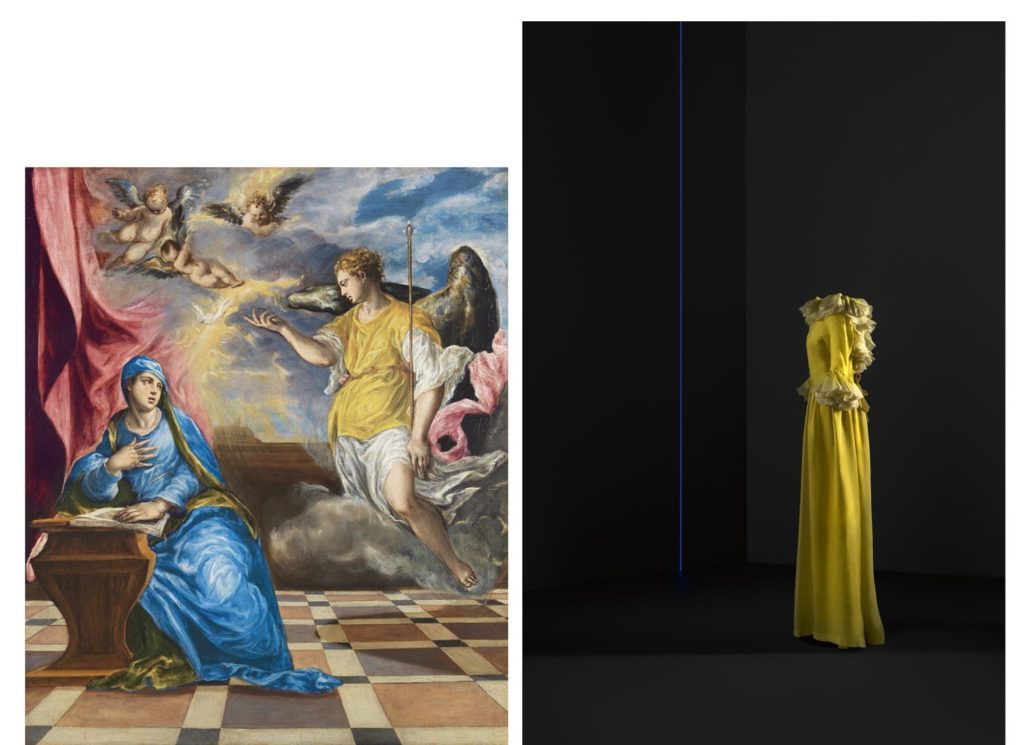

El Greco

Leaving aside the debate about El Greco‘s nationality, he was one of Balenciaga’s major inspirations. One of the things that El Greco is known for is his use of vivid colors. The vibrant colors penetrated Balenciaga’s mind and imagination. For example, he took the vibrant yellow of the archangel Gabriel from The Annunciation and created a beautiful mustardy evening gown from silk organza.

Left: El Greco, The Annunciation, c. 1576, oil on canvas, © Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain.

Left: El Greco, The Annunciation, c. 1576, oil on canvas, © Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain.

Right: Balenciaga, Evening gown, 1968, silk organza, Colección de Dominique Sirop, Paris, France.

Likewise, he created another beautiful evening dress from silk, in a bright pink inspired by another Annunciation of El Greco.

El Greco, The Annunciation, 1609, Private collection, Madrid, Spain.

El Greco, The Annunciation, 1609, Private collection, Madrid, Spain.

Balenciaga, Evening gown, 1962, silk, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain.

Balenciaga, Evening gown, 1962, silk, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain.

Francisco Goya

Balenciaga was fascinated by Goya‘s ability to illustrate the fabrics in full detail. Goya painted in such a manner that one could see the transparency of textiles such as lace, trimmings, tules. Balenciaga became obsessed and began to use them in his designs.

Left: Balenciaga, Evening gown, 1963, satin, pearls and beads, Cristóbal Balenciaga Museoa, Getaria, Spain.

Left: Balenciaga, Evening gown, 1963, satin, pearls and beads, Cristóbal Balenciaga Museoa, Getaria, Spain.

Right: Francisco de Goya, La reina María Luisa con tontillo, c. 1789, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Left: Francisco de Goya, El cardenal don Luis María de Borbón y Vallabriga , c. 1800, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Left: Francisco de Goya, El cardenal don Luis María de Borbón y Vallabriga , c. 1800, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Right: Balenciaga, Dress and jacket outfit, 1960, satin dress, satin jacket with metallic thread, sequins and ceramic beads, 1960, Museo del Traje, Madrid, Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, Spain.

Another possible influence of Goya is Balenciaga’s inclination for separating a flowing shape with a strong line. An example of this is Goya’s portrait of the Duchess of Alba, whose dress is separated by a red belt tied around her waist. Balenciaga created a very similar one.

Fransisco de Goya, La duquesa de Alba de blanco, 1795, oil on canvas, Fundación Casa de Alba. Palacio de Liria, Madrid, Spain.

Fransisco de Goya, La duquesa de Alba de blanco, 1795, oil on canvas, Fundación Casa de Alba. Palacio de Liria, Madrid, Spain.

Balenciaga, Coctail dress, c. 1955 – 1960, floral silk organza and velvet, Museo del Traje, Madrid, Spain.

Balenciaga, Coctail dress, c. 1955 – 1960, floral silk organza and velvet, Museo del Traje, Madrid, Spain.

Diego Velázquez

The works of Velázquez also had a major impact on Balenciaga. What caught Balenciaga’s attention was the shape of Velázquez’ dresses. Actually, that is how he was came up with the Infanta dress in 1939. He reinterpreted the shape by creating a narrow skirt and a less exaggerated shape.

Diego Velázquez, Portrait of the Infanta Margarita Teresa, between 1651 – 1673, The Louvre, Paris, France.

Diego Velázquez, Portrait of the Infanta Margarita Teresa, between 1651 – 1673, The Louvre, Paris, France.

Balenciaga, Infanta dress, 1939, silk, Costume Institue of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Balenciaga, Infanta dress, 1939, silk, Costume Institue of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Diego Velázquez , Las Meninas, c.1656, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Diego Velázquez , Las Meninas, c.1656, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Balenciaga, Evening cape, 1963, silk gazar, silk satin, Victoria and Albert Museum (temporary loan), London, UK.

Balenciaga, Evening cape, 1963, silk gazar, silk satin, Victoria and Albert Museum (temporary loan), London, UK.

Francisco de Zurbarán

Zurbarán is known mostly as a religious painter. As the “first fashion stylist of art history”, according to curator Martínez de la Pera, he painted portraits with outfits that today could be on the catwalk. Balenciaga skipped the holiness and paid attention to the clothing. He really liked the voluminous skirts and he recreated them in his own version.

Left: Balenciaga, Dress and overskirt evening ensemble, c.1951, cotton tulle dress embroidered with metallic thread over rayon satin, silk taffeta overskirt, Museo del Traje, Madrid Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, Spain.

Left: Balenciaga, Dress and overskirt evening ensemble, c.1951, cotton tulle dress embroidered with metallic thread over rayon satin, silk taffeta overskirt, Museo del Traje, Madrid Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, Spain.

Right: Francisco de Zurbarán, Saint Elisabeth of Portugal, c. 1635, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Francisco de Zurbarán, Saint Casilda, c. 1630 – 1935, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain.

Francisco de Zurbarán, Saint Casilda, c. 1630 – 1935, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain.

Balenciaga, Evening dress and cape, 1962, wild silk satin, Collecció Antoni de Montpalau: María del Carmen Ferrer-Cajigal, marquesa de Torroella de Montgri, Sabadell, Spain.

Balenciaga, Evening dress and cape, 1962, wild silk satin, Collecció Antoni de Montpalau: María del Carmen Ferrer-Cajigal, marquesa de Torroella de Montgri, Sabadell, Spain.

Moreover, Balenciaga was fascinated by the way Zurbaran painted his monks with lustrous ivory clothes. When Franco’s granddaughter, Carmen Martínez Bordiú, and Queen Fabiola of Belgium reached out to him for their wedding dresses, Balenciaga created masterpieces.

Left: Francisco de Zurbarán, Fray Francisco Zúmel, c. 1628, Museo de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid, Spain.

Left: Francisco de Zurbarán, Fray Francisco Zúmel, c. 1628, Museo de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid, Spain.

Right: Balenciaga, Wedding dress, 1960, satin and mink, Cristóbal Balenciaga Museoa, Getaria, Spain.

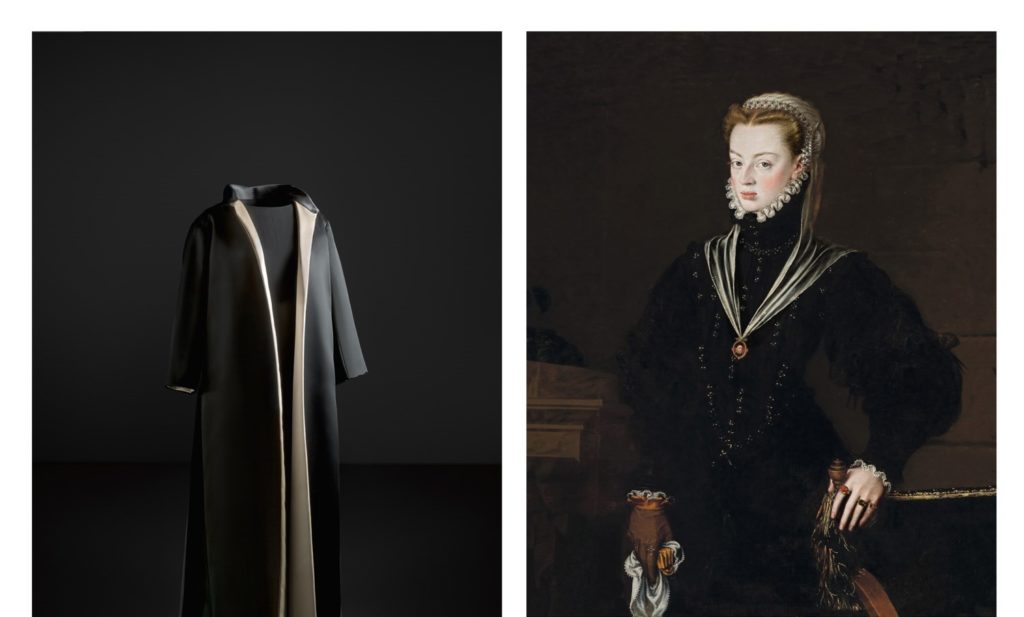

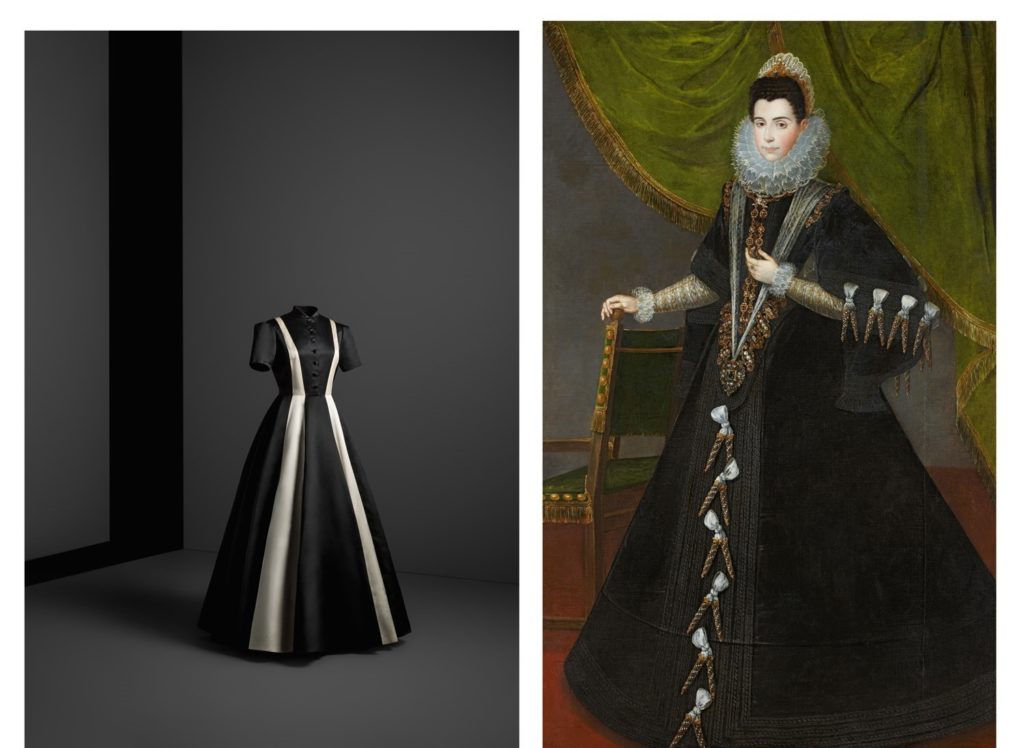

Court Painting

Balenciaga was a very religious man. So, it is no surprise that when he came across the Spanish court paintings of the 16th and 17th century, he was enchanted. The deep black of the women’s dresses, depicted in paintings of holiness, became one of Balenciaga’s distinguishing features. In the 1950s, he gave a twist to the austere dresses, giving them an unholy personality, with feathers, sequins and capes.

Left: Balenciaga, Reversible evening coat, 1966, satin, Cristóbal Balenciaga Museoa, Getaria, Spain.

Left: Balenciaga, Reversible evening coat, 1966, satin, Cristóbal Balenciaga Museoa, Getaria, Spain.

Right: Alonso Sánchez Coello, Retrato de doña Juana de Austria, princesa de Portugal, c. 1557, Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, Spain.

Left: Balenciaga, Evening gown, 1943, satin, Cristóbal Balenciaga Museoa, Getaria, Spain.

Left: Balenciaga, Evening gown, 1943, satin, Cristóbal Balenciaga Museoa, Getaria, Spain.

Right: Anonimo Español del Siglo XVII, Portrait of the VI Countess of Miranda, Fundación Casa de Alba, Palacio de Liria, Madrid, Spain.

Juan Pantoja de la Cruz, Queen Elisabeth of Valois, third Wife of Philip I, c. 1605, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Juan Pantoja de la Cruz, Queen Elisabeth of Valois, third Wife of Philip I, c. 1605, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Balenciaga, Cocktail dress, c.1963, synthetic, Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Balenciaga, Cocktail dress, c.1963, synthetic, Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Balenciaga, Cocktail dress, c.1963, cotton, silk, Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Balenciaga, Cocktail dress, c.1963, cotton, silk, Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Balenciaga, Cocktail dress, 1955, wool, Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Balenciaga, Cocktail dress, 1955, wool, Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

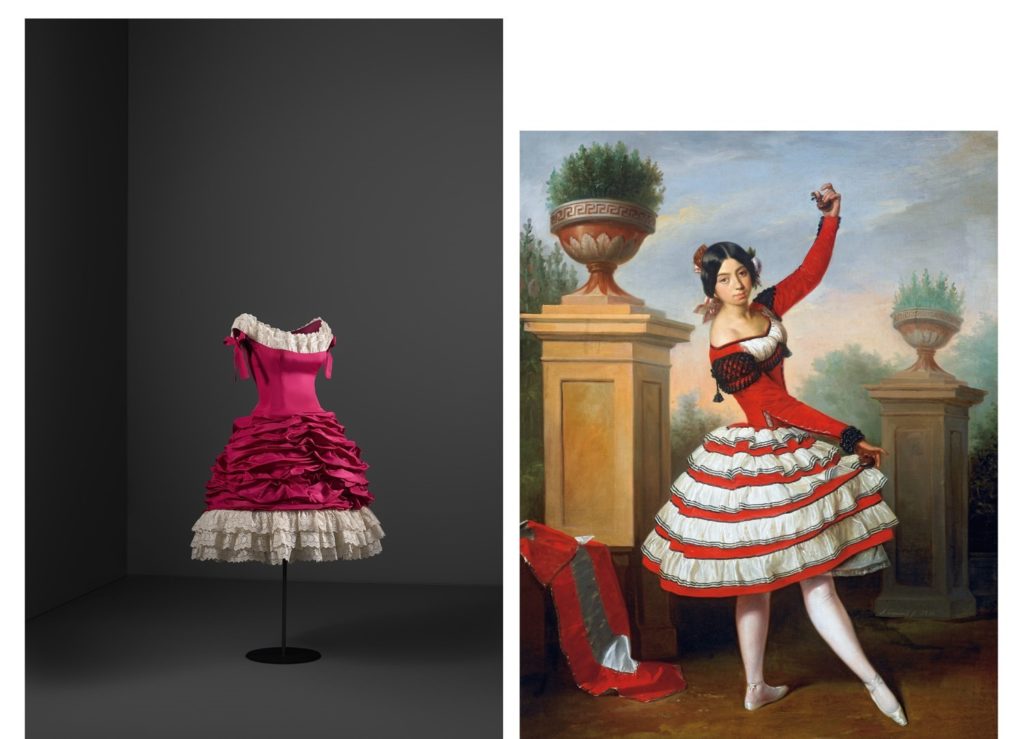

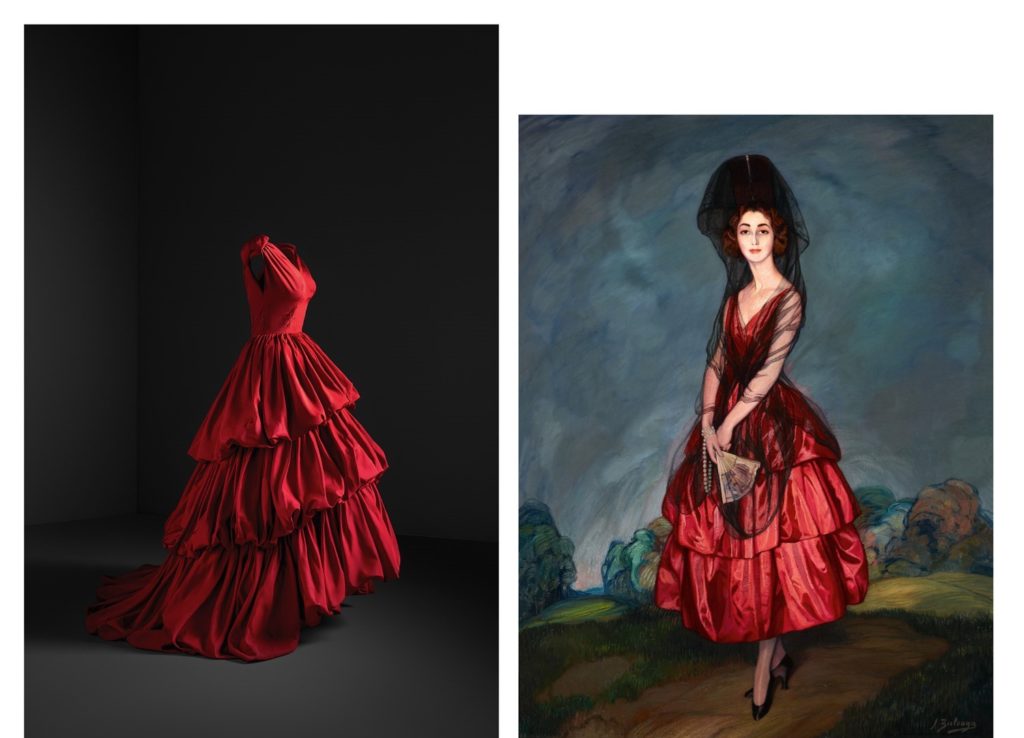

Flamenco

Another major part of Spanish culture is the flamenco dance. Balenciaga thereby made several pieces that were very similar to flamenco dresses, but he always added his personal touch. The dresses, designed in the 1950s and 1960s, have the typical flamenco skirt, which has ruffles and is either open or shorter at the front and closed or longer accordingly at the back. This pattern can be found even in recent designs of the House of Balenciaga.

Left: Balenciaga, Cocktail dress, 1955, taffeta and embroidered cotton trim, Cristóbal Balenciaga Museoa, Getaria, Spain.

Left: Balenciaga, Cocktail dress, 1955, taffeta and embroidered cotton trim, Cristóbal Balenciaga Museoa, Getaria, Spain.

Right: Antonio María Esquivel, The Dancer Josefa Vargas 1850, Colección Duques de Alba, Palacio de las Dueñas, Sevilla, Spain.

Left: Balenciaga, Evening gown, 1952, taffeta, Cristóbal Balenciaga Museoa, Getaria, Spain.

Left: Balenciaga, Evening gown, 1952, taffeta, Cristóbal Balenciaga Museoa, Getaria, Spain.

Right: Ignacio Zuloaga, Portrait of María del Rosario de Silva y Gurtubay, Duchess of Alba, 1921, Fundación Casa de Alba, Palacio de Liria, Madrid, Spain.

Balenciaga, Evening dress, 1951, silk, Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Balenciaga, Evening dress, 1951, silk, Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Balenciaga S/S 2012, photo: Imaxtree.

Balenciaga S/S 2012, photo: Imaxtree.

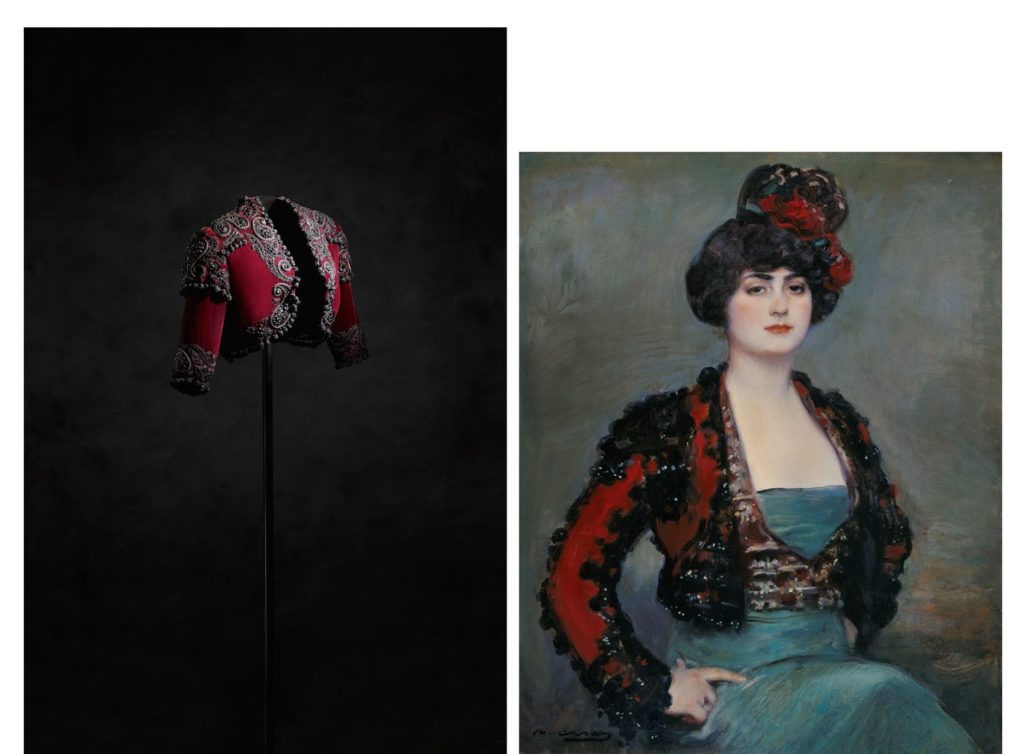

Bullfighting

Bullfighting was also a part of the Spanish tradition from which Balenciaga drew inspiration. His hats and certain boleros were in accordance to the tradition of the matadors. The difference is that the Balenciaga ones are fringed, tasseled and they have sequins. In addition, the bullfighting concept is present in recent runways too.

Left: Balenciaga, Evening jacket, 1946, silk velvet, passementerie and jet beads, Hamish Bowles Collection.

Left: Balenciaga, Evening jacket, 1946, silk velvet, passementerie and jet beads, Hamish Bowles Collection.

Right: Ramón Casas Carbó, Julia, c.1915, Colección Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza in temporary loan to Museo Carmen Thyssen Málaga, Spain.

Left: Balenciaga, Bolero jacket,1947, Museo Cristóbal Balenciaga, Getaria, Spain.

Left: Balenciaga, Bolero jacket,1947, Museo Cristóbal Balenciaga, Getaria, Spain.

Right: Balenciaga, Lace cape, c. 1960, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

Balenciaga S/S 2013, photo: Vogue.

Balenciaga S/S 2013, photo: Vogue.

Balenciaga, Hat, 1955, straw, Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Balenciaga, Hat, 1955, straw, Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Balenciaga, Hat, 1958, cotton, plastic, Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Balenciaga, Hat, 1958, cotton, plastic, Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

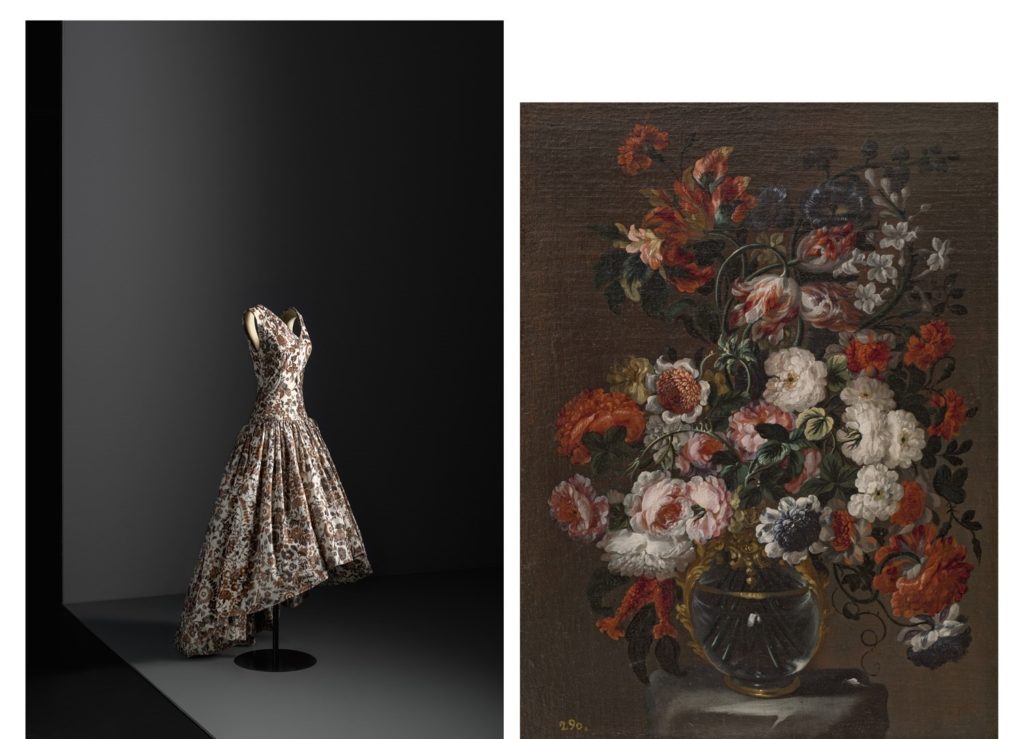

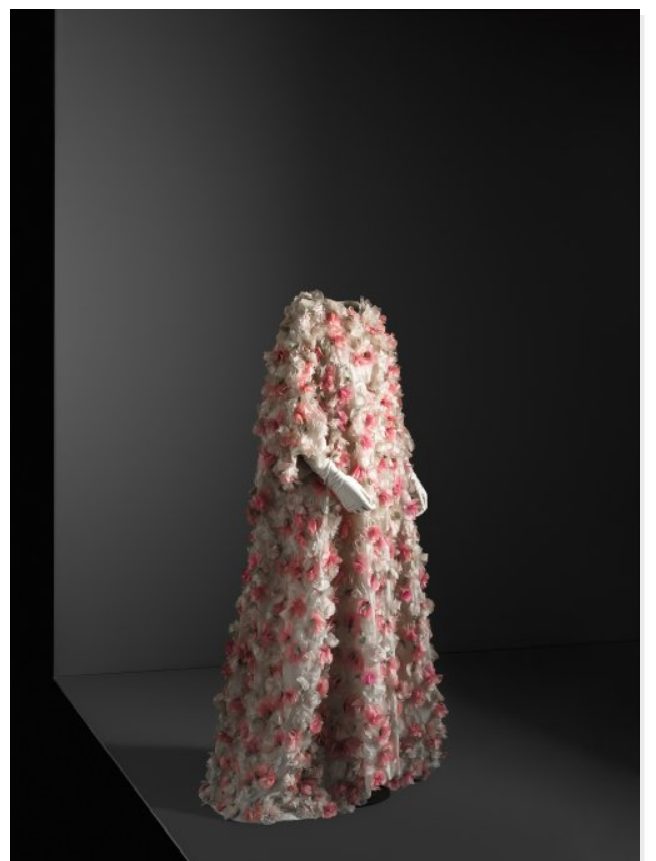

Still-Life

Beautiful and chic flowers from the still-life paintings of the court bloomed in Balenciaga clothes. Balenciaga applied them on evening coats or embroided them in evening gowns, using silk thread, sequins and shiny beads.

Left: Balenciaga, Evening gown, c. 1958, silk Ikat, Colección de Inés Carvajal.

Left: Balenciaga, Evening gown, c. 1958, silk Ikat, Colección de Inés Carvajal.

Right: Gabriel de la Corte, Flowers in a Glass Vase, second half of the 17th century, Colección Gerstenmaier.

Juan van der Hamen y León, Ofrenda a Flora, 1627, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Juan van der Hamen y León, Ofrenda a Flora, 1627, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Balenciaga, Evening coat, 1964, organza with flower appliques, Museo Cristóbal Balenciaga, Getaria, Spain.

Balenciaga, Evening coat, 1964, organza with flower appliques, Museo Cristóbal Balenciaga, Getaria, Spain.

*all the mentioned pieces are a general reference to the artistic inspiration of Balenciaga, they are not all from the exhibition at the Museo Nacional Thyssen – Bornemisza.