The woman who painted her body for artist Yves Klein

The woman who painted her body for artist Yves Klein

-

Published

21 October 2016

Image source,

Getty Images

Image caption,

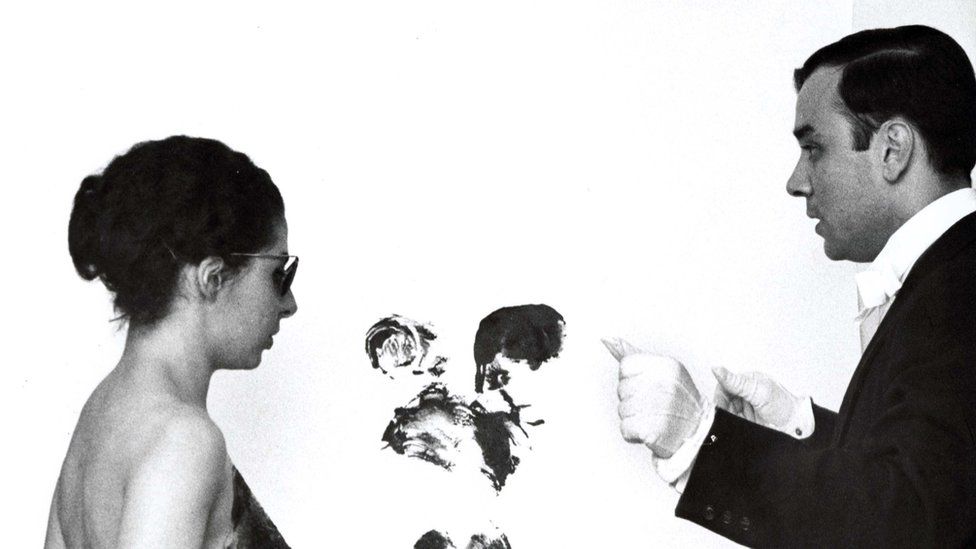

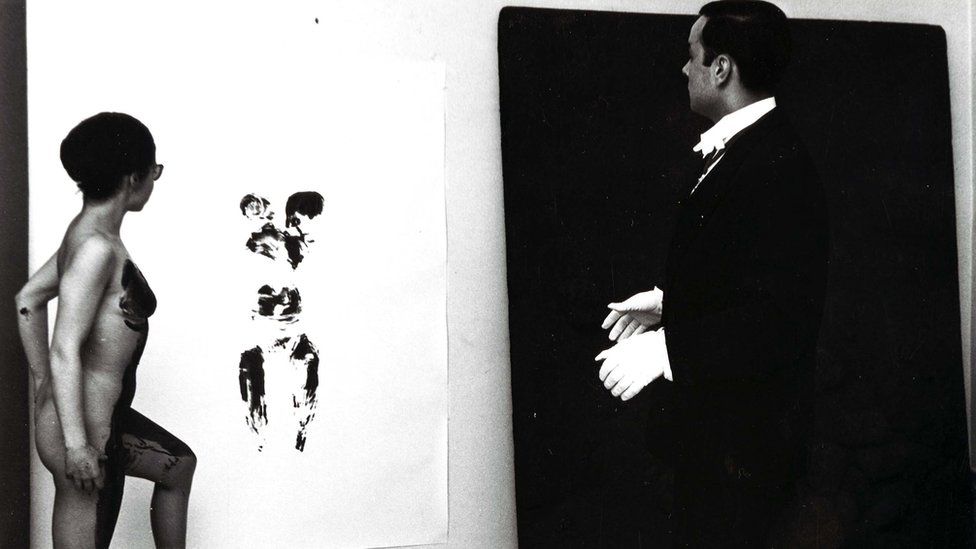

Elena Palumbo-Mosca covered her body in blue paint for Yves Klein’s Anthropometry works

In a Paris art gallery in 1960, three naked women covered themselves in blue paint and made impressions of their bodies on paper as an orchestra played and guests wearing formal dress looked on.

It has come to be seen as one of the landmark events in the history of performance art.

The evening was conducted by French artist Yves Klein, who wore a black dinner jacket and white bow tie for the occasion, and who gave us a radically different type of nude in art.

But there has been criticism of the way Klein used young women – dubbed “living paintbrushes” – as his instruments.

One of the women who painted their bodies and Klein’s canvases that night, and on numerous other occasions, was Elena Palumbo-Mosca.

As some of Klein’s Anthropometry paintings go on show at Tate Liverpool, Ms Palumbo-Mosca, now 81, rejects the notion that she was exploited and says she was more than just a “living brush” or a traditional passive model.

![]()

Image source,

Elena Palumbo-Mosca

Image caption,

Elena Palumbo-Mosca: “I was not a paintbrush because, in spite of all, I did use my brain”

How did you meet Yves Klein?

I worked as an au pair girl in Nice.

At that time, I was very happy to know young French men because they were so charming and they knew how to speak to a young woman with the right words.

And Yves was particularly charming and very good looking.

Then, later on, I was living in Paris, so when Yves needed a person to do the prints, the Anthropometry, he thought that I could do this job.

We liked each other, we were often together, dining or just spending time together, so it was absolutely normal that he should ask me.

![]()

Did you have any reservations?

No, because I’ve always been somehow facing the public.

As a young girl I was a springboard diver, so I was used to being in front of the public.

Then, I worked in Paris as a dancer in nightclubs.

So it was not a problem to use my body and face the public, because I was used to it.

![]()

How did he ask you to make the artwork?

“There is a bucket of paint, you put the paint on that and that and that part of your body, and then you make a print.”

![]()

There was no more direction than that?

Not really. In a way, he kept to himself whatever he thought was the real meaning of Anthropometry, and this is why there are so many interpretations.

The impression I got was that he wanted to give a new beginning to representation using the central part of the body.

The head is excluded, so it was just the physical functions of the body that were giving their energy to the print.

It was not a mental process.

But perhaps he meant many things, and perhaps some artists are doing things as if they were in a trance and not really being aware of the implications.

I don’t know.

I was just a co-operating person.

![]()

You were a paintbrush?

No, I was not a paintbrush, because, in spite of all, I did use my brain.

I was not a brush, I was a person who co-operated.

He called us his collaborators, in fact.

The expression “living brushes” sounded great, but it was not too kind to the person who was doing the work with Yves.

![]()

Image source,

Getty Images

Image caption,

Works from the Anthropometry series have sold for more than $12m (£9.8m)

What do you remember of the experience in the gallery?

I always enjoyed provoking the entourage, so I thought it was funny to see all those stiff people suddenly finding themselves in front of three naked women making prints, and the music being there, and the musicians probably were also quite surprised but they couldn’t show it.

I don’t think there was ever a wrong print – they were all always supposed to be good, good for me and for Yves.

That means we were working with a lot of precision and working seriously.

It was not a funny thing, even if we looked as if we were doing something funny.

It was in fact very strenuous.

Some of the Anthropometries needed a lot of physical strength.

We worked with fire and water [on other paintings].

It took a long time.

It was cold and so on.

You have to be quite strong physically and to do hard work without complaining and without looking tired, which is something sports and show-business gave me.

![]()

How many paintings did you take part in?

Quite a lot – we were doing steady ones and ones where he was pulling me and it looked like I was diving and there were the ones on round paper, then there were the fire and water prints.

He was a hard worker.

![]()

Did you feel like you were being exploited?

No, not at all. When an actress does what a film director asks her to do, she’s not exploited, she’s just co-operating.

He was like a director in a way and we were doing exactly what he wanted us to do, but we also wanted to do it.

![]()

Did he ask men to do the same?

I think he did it with himself and perhaps a couple of men.

There are some. I think there is a huge one where there is a man flying around in space in a print.

But perhaps it was a hint to the fact there should be more women artists.

There are not so many in history so far.

![]()

A lot of people would say he was the artist and you were the object.

No, we were subjects.

The model traditionally was always an object for the painting, object for the public.

But there, especially when we did the presentation in public, we were all subjects.

Also, for the public, we were acting.

We were not just still objects.

I think things are a bit more complex.

![]()

How do you feel about the works now?

Oh, I like it very much.

I will disappear sooner or later, unfortunately quite sooner because I’m nearly 82.

But there will be some prints of mine around.

There could be some DNA in the blue paint!

![]()

Yves Klein is on at Tate Liverpool from 21 October to 5 March 2017. Ms Palumbo-Mosca will speak at the gallery on 26 November.

![]()

Follow us on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, on Instagram at bbcnewsents, or, if you have a story suggestion, email [email protected].

Around the BBC

-

Yves Klein: The man who invented a colour – BBC Culture

Related Internet Links

-

Yves Klein at Tate Liverpool

The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites.