Vietnam | LandLinks

Mục lục

LAND USE

Vietnam is situated in Southeast Asia amid the Gulf of Thailand, the South China Sea and the Gulf of Tonkin. It borders China, Laos and Cambodia. The country contains 31,007,000 hectares, and the 2011 population was 87.8 million. The population is growing at an annual rate of 1%. Seventy percent of the population lives in rural areas, working primarily in agriculture. Vietnam’s 2011 GDP was US $124 billion, with 20% attributed to agriculture, 40% to industry and 40% to services. Vietnam is the world’s second-largest exporter of rice (its top export commodity), exporting over 7 million metric tons in 2011. Other top exports include crude oil, clothes and shoes, marine products, wood products, electronics, coffee, cassava, rubber, fresh fruit, cashews and tea (World Bank 2012a; World Bank 2010b; BBC 2011; VFA 2012; FAO 2009; CIA 2012).

About one-third of Vietnam’s land area is used for agriculture, with 20% of its land considered arable, 11% used as permanent cropland and about 2% used as permanent meadow and pastureland. Vietnam’s top agricultural products are paddy rice, coffee, rubber, tea, pepper, soy beans, cashews, sugar cane, peanuts, bananas, poultry, fish and seafood. About 45% of Vietnam’s agricultural land (or 15% of its total land area) is irrigated. Seven to ten million hectares of Vietnam’s total area are wetlands, at least half of which are located in the Red and Mekong River Deltas (World Bank 2012a; FAO 2009; CIA 2012; Nang 2003).

Vietnam has diverse natural forests, including evergreen and semi-evergreen broad-leaved forests, semi-deciduous and dry deciduous forests, mixed evergreen coniferous forests and mangroves. Forests cover about 45% of Vietnam’s land area. The country has undertaken a vast reforestation effort over the last 20 years, averaging an annual afforestation rate of 1% between 2005 and 2010 (World Bank 2010a; World Bank 2012a; FAO 2010).

Evidence has emerged of land degradation caused by unsuitable agricultural and land management practices. In the northern mountains, arrested crop succession and forest clearing, especially when linked to a shift toward drier regeneration, are leading to soil erosion and loss of biodiversity in favor of imperata grasslands. In intensively irrigated rice plantations in lowland areas, waterlogging and nutrient imbalances are preventing land productivity gains (World Bank 2010b).

Vietnam has one of the world’s lowest per capita land endowments, with less than 0.3 hectares of agricultural land available per person. Most suitable lands are being utilized. Intensity of land use is high, especially in areas of human settlement and wetland rice agriculture, and is increasing within other categories of use as well. The average number of paddy crops has increased to nearly two per plot-year (World Bank 2010b).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

The current distribution of land in Vietnam stems from a series of reforms that extend as far back as 1954. From the mid-1950s to 1975, the nation was divided into two countries: the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the north, and the Republic of Vietnam in the south. Each country had a different agrarian structure. Communist reforms in the 1950s imposed agricultural collectivization in the north, while the south carried out a land-to-the-tiller program in the 1970s. The latter process provided ownership rights to former tenant farmers and led to approximately three-quarters of tenant households receiving rights to roughly 44% of the farm area in the south. This allocation to smallholders resulted in a 30% increase in rice production. The land-to-the-tiller reforms were largely lost when the Communists took power in 1975, but laid the foundation for the practice of household farming that spread across the country following decollectivization in the 1980s (Prosterman and Brown 2009).

In the late 1970s, almost 97% of rural households in the north belonged to collectivized farms. Although Communist leadership attempted to collectivize the south, peasant households resisted, and only 24.5% joined cooperatives. Collectivized areas in the north and the south experienced low and declining agricultural growth and food grain availability (Kirk and Tran 2009).

The government eventually suspended its failing attempt to collectivize the south, and implemented a series of measures in the late 1980s to transition Vietnam to a market-oriented economy. These steps, known as the Doi Moi reform process, included the allocation of land-use rights to farmers. By 2009, the state had allocated 72% of Vietnam’s total land area and almost all of its agricultural land to land users, with cropland allocation among farm households being relatively equitable as compared with many other developing and transitional countries. Farm sizes vary, but are typically around 0.2 hectares per capita (Kirk and Tran 2009; World Bank 2010b; Marsh and MacAulay 2006).

Farms in the Mekong Delta region occupy 1.2 hectares on average, which is considerably larger than farm sizes in the Red River Delta area (Marsh and MacAulay 2006).

Land allocation processes vary by district. Generally, equity between households is a key consideration, and the process takes into account the number of people in a household and the quality of the land. Typically, the total amount of land allocated varies among households and each household’s land is split into plots of varying quality. There are now approximately 70 million parcels of land in Vietnam (Marsh and MacAulay 2006).

Vietnam has more than 50 distinct ethnic groups, including the Kinh (Viet) majority group (85.6%). Kinh families are more likely than other families to have high-quality irrigated land. In the central highlands, where coffee and other cash crops are a source of rural development, Kinh are much more likely to have perennial cropland, which has been important in enabling rural households to diversify income sources (World Bank 2008).

Minority groups account for about 15% of the population and include the Tay (1.9%), Muong (1.5%), Khmer (1.5%), Mong (1.2%), Nung (1.1%) and others (7.2%). These groups tend to have higher poverty rates, in part due to the lower quality of their land, and are concentrated in the upland and mountainous areas of the central and northern highlands. The Khmer are based primarily in Vietnam’s lowlands, and the Tay, Muong and Nung tend to be valley-dwelling rice farmers in the northern mountains. Ethnic minorities often reside near forestland but do not have consistent access to forests. In the northwest region, half of all ethnic minority households report using forestland. In the central highlands, which hold the country’s largest forest area, only 4% of ethnic minorities report that they have forest use access (CIA 2012; Ravallion and van de Walle 2008; Dang 2009; World Bank 2008).

Minority groups rely heavily upon land for their livelihood. Their production and land-use practices differ from the ethnic majority’s practices, focusing more on shifting cultivation, forestry and communal tenure arrangements. More than 90% of ethnic minority households dependent upon agriculture have land that they use for annual crops. Those who do have annual cropland tend to have more of it than the Kinh and Chinese (majority population), though this does not necessarily represent an advantage, as much of this land is on sloping terrain and yields only one crop per year. Whereas upland agriculture is an essential part of most ethnic minority livelihoods, the state has not focused agricultural research or extension efforts on understanding and improving upland agriculture. For example, research has not sufficiently addressed diminishing fallow times, which present a challenge for upland farming systems. Instead, the state has emphasized policies that have little impact on ethnic minorities, such as those that encourage the production of wet rice in valleys (Ravallion and van de Walle 2008; World Bank 2008).

In 2003, Vietnam reported that 10.4 million farm households (90% of households using agricultural land) had received land-use right certificates (LURC). By 2010, the state had issued approximately 31.3 million LURCs, covering roughly half of Vietnam’s land area. Certification rates differed between land categories and were lower for non-agricultural land other than residential land and forestland (Hartl 2003; World Bank 2010b).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The formal law governing land rights includes the 1992 Constitution of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (amended in 2001), the 1986 Marriage and Family Law (revised in 2000), the 1995 Civil Code (amended in 2005), the 1993 Land Law (amended in 1998 and 2001) and the 2003 Law on Land.

The Constitution vests all land – including forests, rivers and lakes, water sources and underground natural resources – in the population as a whole. It also provides that the state is to systematically manage all land and allocate it to organizations and individuals, and that those to whom land has been allocated are entitled to transfer their right of use to others.

The 1986 Marriage and Family Law (revised in 2000) and the 1995 Civil Code (amended in 2005), govern matters relating to family, marital property rights and inheritance (FAO 2012a).

The 1993 Land Law is credited with laying the foundation for a formal land market by providing increased land-tenure security, facilitating access to credit, and bolstering the transferability of use rights. It formalized the farm household as the main unit of agricultural production, and provided for the allocation of land-use rights to households, vesting in them the power to purchase and use inputs, sell outputs from the land and (to some degree) to make decisions regarding the use of land. The law also provides that land users may exchange, transfer, bequeath, lease and mortgage their rights, and requires the state to issue land-use right certificates (LURC) at the household level. Additionally, it increased tenure security by providing for use-right grants of 20 years for annual cropland (further increased to 30 years in a 1998 revision) and 50 years for perennial cropland. The law also imposed ceilings of 2 to 3 hectares on annual cropland and 10 hectares on perennial cropland, and addressed leasing of land to foreigners. Decree 64 of 1993 further delineated the local application of ceilings in various provinces (Marsh and MacAulay 2006; Haque and Montesi 1996).

Revisions in 1998 added the rights to sublease LURCs and to use them as capital in joint venture arrangements (Marsh and MacAulay 2006).

The 2003 Law on Land supported Vietnam’s transition to a market-oriented economy. It dealt with many aspects of land-use planning and land administration systems, decentralized many land administration responsibilities to local government structures and established policies and procedures to govern compulsory acquisition of land by the state. It also required that LURCs include names of both the husband and the wife if the land belongs to both, and required right holders to obtain an LURC to exchange, transfer, bequest, lease and mortgage land rights (Hatcher et al. 2005; World Bank 2010b; GOV Law on Land 2003).

Although the 1993 Land Law stipulated that the state should issue long-term use rights to various non-state entities, the law did not mention customary groups such as village communities, hamlets or groups of households, and as a consequence such groups were not eligible to receive land use rights. The 2003 Law on Land sought to remedy this defect, and authorized the state to issue use rights to such customary groups (EASRD 2004).

Vietnam’s legal system has not recognized customary laws since 1975. However, in areas where the state does not have the capacity to administer state law, customary rules are often an important source of regulation for social relations, ownership rights, property disputes and issues of marriage, inheritance, contract and tort. In minority and ethnic communities, customary rules are often the first choice for dispute settlements (Phan 2011).

In October 2012, Vietnam’s National Assembly began considering a law to amend the 2003 Law on Land. The full scope of the new law is unclear, but government officials have indicated that it will address compulsory acquisition mechanisms and processes for determining the market price of land. It is also expected to address the expiration of 20-year land-use rights that the government granted to land users in 1993 (VCCI 2012; GOV 2012c; Hiebert 2012).

TENURE TYPES

As noted above, individuals, households and organizations cannot own land, as it belongs to the people as a whole. However, following the 1993 Land Law, the state may either allocate land-use rights, or lease land to individuals, households and organizations, who thereby acquire usufruct rights. This right includes the right to receive a land-use right certificate (LURC), to lease out, exchange, mortgage and bequeath the use right, and to exclude others from the land. This right also allows for land transactions that, while they are the equivalent of sales, are referred to as transfers, or chuyen nuong dat (Ngo 2005; GOV Law on Land 2003; EASRD 2004).

Use rights, which may extend for 20 or 50 years depending on their type (annual cropland, perennial cropland or forestland) do not include the right to determine how land is used, which the state reserves the right to decide. Transfers of use rights require the transferor to possess a registered LURC and must be for a period within the term initially granted to the transferor (GOV Law on Land 2003; EASRD 2004).

Several categories of legal entities may acquire land-use rights. The state can grant use rights either through allocation or lease, and some rights may require the user to pay fees or rent. By law, categories of “land users” include: (1) domestic organizations (e.g., political organizations and units of the People’s Armed Forces), which are allocated land by, lease land from or have land-use rights recognized by the state; (2) economic organizations that receive land-use rights by transfer; (3) communities of citizens whose use rights are allocated or recognized by the state; (4) domestic households and individuals, who are allocated land by the state, lease land from the state, have land-use rights recognized by the state or receive a transfer of such rights; (5) religious establishments, which receive land-use rights through state allocation or recognition; (6) foreign organizations with diplomatic functions, to which the state may lease land; (7) certain Vietnamese residing overseas, to whom the state may allocate or lease land; and (8) foreign organizations and individuals investing in Vietnam, to whom the state may lease land (GOV Law on Land 2003).

The law authorizes the state to allocate land to certain entities for particular kinds of use. These include: (1) households and individuals working directly in agriculture, forestry, aquaculture or salt production; (2) agricultural cooperatives using land for direct service production in agriculture and forestry; and (3) communities using agricultural land. In these cases, the holder of the use right is not required to pay use fees. Holders of other allocated use-rights are required to pay use fees, including, for example, households and individuals using residential land, and economic organizations using land for agriculture, forestry, aquaculture or salt production (GOV Law on Land 2003).

In the case of certain other use rights, the state leases out land and requires the user to pay annual rent or a one-time payment for the entire lease term. Rights in this category include: (1) those of households and individuals to use land for production in agriculture, forestry, aquaculture and salt production; and (2) various entities implementing investment projects (GOV Law on Land 2003).

The 2003 Law on Land includes a kind of communal land tenure, stating that, “land allocated by the State to a community of citizens shall be used to preserve the national identity through the habits and customs of ethnic minority people.” Vietnam’s legal system has not recognized customary laws since 1975. In some areas, however, occasional remnants of customary communal land tenure can be found. For example, a World Bank study found that communal land-tenure rules have remained predominant over state rules in some provinces, with land being allocated to households each year by a village elder. In these areas, individual private land-tenure rights were not widespread and were not locally recognized (GOV Law on Land 2003, Art. 71; Phan 2011; Andersen 2011).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

There are numerous means by which Vietnamese may acquire rights to land. One is through state allocation or lease, which typically means that an authority assigns usage of a specific land plot to a particular land user. When collectivized agricultural land was redistributed in the late 1980s and early 1990s, allocation played a primary role in providing farmers access to agricultural land in north and central Vietnam. Land users can also acquire land-use rights through inheritance or grant from family members, through land market transactions, and as the result of land reclamation efforts. For firms and other organizations, state allocation continues to be a primary means for acquiring access to land (World Bank 2010b).

The predominant means by which households have acquired rights to land may vary by region. Findings from a 2001 study of 400 farm households in four provinces found that a high percentage of land was acquired through allocation in the north, whereas in the south more users had acquired land through inheritance (Marsh and MacAulay 2006).

There are three main mechanisms through which investors can acquire land-use rights from the state: (1) allocation, whereby the state adopts an administrative decision to grant use rights to a national entity; (2) recognition, also available for national entities only; and (3) leasing, in which the state provides use rights on a contract basis to national and foreign entities. Foreigners may only obtain use rights through lease and must pay a land-use rent. In the case of foreign entities, leases must be based on economic or technical justifications approved by a state body. Articles 80 through 84 of the 1993 Land Law contain provisions regarding the leasing of land to foreigners (Embassy of Vietnam 2012; Haque and Montesi 1996).

Land-use right certificates (LURC) signify formal state recognition of a user’s rights, and are necessary for secured tenure, formal land transactions, access to formal credit and legal protection of land-use rights. They also contain information on the land user and the land parcel, and description of the property (Tran Nhu 2006).

The 2003 Law on Land required the state to establish land registration offices in all provinces for the registration of land transactions. Under this law, all parcels and any attachments to land are to be registered in one system (Do 2006).

At the province, district, city and town levels, People’s Committees handle the allocation of land and issuance of LURCs to households and individuals, communities of citizens, religious organizations and establishments, and overseas Vietnamese. They are also responsible for procedures of transfer and exchange of land-use rights, except in rural areas, where these responsibilities belong to People’s Committees at the commune level (FAO 2012a; GOV Law on Land 2003).

In cases where a particular parcel has multiple users, whether individuals, family households or organizations, the state should issue certificates to each co-user. Under the Marriage and Family Law, land acquired during a marriage is deemed a common asset. That law requires that the names of both husband and wife be registered on LURCs. Additionally, the 2003 Law on Land requires that LURCs include the name of both husband and wife if the land is a mutual asset. If the wife’s name is on the certificate, her rights to the land are protected in the case of separation, divorce or the death of her husband. These laws are not being implemented fully. As of 2010, only about 30% of LURCs included the names of both spouses. This figure appears to refer to LURCs for both agricultural and non-agricultural land, and the percentage for agricultural land alone may be lower, as discussed further below (GOV Law on Land 2003; Hatcher et al. 2005; World Bank 2010b).

While the law gives households the right to sell, rent, exchange, mortgage and bequeath their land, many do not have the right to determine how they use their plots. The state predetermines land-use designations (Markussen et al. 2009; World Bank 2010b).

Although the 20-year land-use rights that the state granted to land users in 1993 will expire in 2013, criteria and procedures for extending their duration are unclear. This contributes to a perception of insecurity and affects the security and certainty of rights in practice. A new land law, which the National Assembly began considering in October 2012, is expected to address the expiring rights. Reports indicate that the new law will tend to preserve existing allocations of those with expiring use-rights (World Bank 2010b; Hiebert 2012; Kirk and Tran 2009).

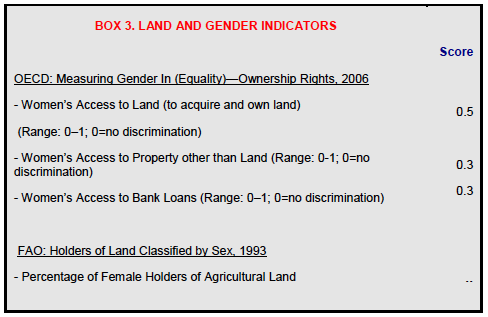

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

A number of factors prevent women from asserting their land rights. These include the following: laws with inadvertent impacts; lineage practices; biased mediation groups and committees; biased testamentary (will-related) practices; lack of access to legal services; lack of enforcement and male privilege (Cầm et al. 2012).

Vietnam’s laws emphasize gender equality, including with regard to land-use rights. The Constitution prohibits all forms of discrimination against women, and states that men and women have equal rights in the family and in political, economic, cultural and social fields. Other laws provide that women have the same rights as men to engage independently in civil transactions, contracts, property management and justice mechanisms. Article 8 of the Civil Code provides that men and women are equal in civil relations (Hatcher et al. 2005).

Vietnam’s laws emphasize gender equality, including with regard to land-use rights. The Constitution prohibits all forms of discrimination against women, and states that men and women have equal rights in the family and in political, economic, cultural and social fields. Other laws provide that women have the same rights as men to engage independently in civil transactions, contracts, property management and justice mechanisms. Article 8 of the Civil Code provides that men and women are equal in civil relations (Hatcher et al. 2005).

The Marriage and Family Law establishes that all land acquired during marriage is considered a common asset, while the 2003 Law on Land requires that LURCs bear the names of both spouses if a land-use right is shared property. By law a wife has the same rights and obligations as her husband in the use, possession and disposition of common property (GOV Law on Land 2003; GOV Marriage and Family Law 2000).

When the 1993 Land Law entitled farmers to trade, transfer, rent, bequeath and mortgage their land-use rights, the change was implemented through the issuance of LURCs at the household level. Though these reforms used gender-neutral language, disparities resulted during implementation. Initially, the LURCs had space for only one name, which was used to record the name of the household head. As men were more often household heads, more men than women had their names on LURCs (Menon and Rodgers 2012; Ravallion and van de Walle 2008).

Although a 2001 decree required that the names of both spouses be listed for jointly held land, government departments responsible for implementation lacked capacity, local officials reportedly reverted to traditions and customary practices favoring men, and the requirement was not well enforced (Menon and Rodgers 2012; Ravallion and van de Walle 2008; Hatcher et al. 2005).

The inclusion of women’s names on LURCs is intended to protect their rights in the case of separation, divorce, or the death of a husband. However, inclusion continues to be low. In the most comprehensive study of women’s access to land rights to date, groups following matrilineal succession reported 11% joint certification over non-residential land, and ethnic minority groups practicing patrilineal succession reported 4.2%. Those from matrilineal groups reported the highest levels of sole certification for wives (21.1%) as compared to non-Kinh patrilineal groups (15.7%). As for residential land, only 22% of married women are listed jointly with their husbands, and 19% solely (Hatcher et al. 2005; Cầm et al. 2012).

Without their names on land-use certificates, women are, in practice, subject to customary practices, which leave them without a share of family assets acquired after marriage in the case of divorce. In the case of a husband’s death, widows often see a son’s name, rather than their own, recorded on the land-use certificate (FAO 2012a).

The Marriage and Family Law requires that the purchase, sale, exchange, giving, borrowing and other deals relating to large-value (joint) property shall be agreed to by wife and husband. However, authority over property generally shifts to husbands upon marriage, and the amount of authority each spouse enjoys depends on cultural practice, social position in the community, language and economic status (GOV Marriage and Family Law 2000; Tran 2001; Cầm et al. 2012).

Though by law women are provided land-use rights equal to men’s, their access to and control of land remains low. Many localities have allocated land on the basis of the age of household members, with working-age individuals receiving larger allocations than others. Female-headed households often have fewer working-age adults, and have therefore tended to receive smaller allotments than male-headed households. Size of allotment is often affected by the assignee’s retirement age, which is 55 for women and 60 for men, with the result that women are typically awarded smaller plots. Of the 12 million farmers allotted land by the end of 2000, only 10% to 12% were women (Menon and Rodgers 2012; Hartl 2003; CEDAW 2005).

Vietnam’s laws on inheritance and succession provide for gender equity that does not exist fully in practice. While men and women have equal rights to transfer property and to inherit according to testament or the law, the law also gives primacy to parental wills. In the vast majority of cases, excepting bilateral and matrilineal groups, families that divide property before death do so without regard to gender equity, and based on a variety of factors, including male preference and customary practice. Where there are both male and female children, males typically inherit property while daughters may inherit a smaller share or be excluded entirely. Due to the prevalence of patrilocal residency (the practice of married couples settling with or near the husband’s family) and to expectations that sons maintain ancestral rites, daughters in families following patrilineal practices do not inherit land equally with their brothers (Cầm et al. 2012).

Succession and inheritance laws that apply in cases of intestate deaths (i.e., in cases where there is no testamentary will) include provisions that can create difficulties for women. For example, a “spouse” is considered under the law to be a member of the first order of succession. The definition presumably refers only to a legal spouse, as according to law there can only be one, meaning that, in areas practicing polygyny, the inheritance rights of second and third wives are vulnerable (Cầm et al. 2012).

Confidence in the willingness of Vietnamese courts to uphold equal rights is reportedly high, though there is concern regarding the lack of mechanisms available for enforcing court decisions. Despite confidence in courts, data show that they draw on the law selectively and decide cases based on overlapping concerns including family, kinship and local cultural practices. Courts have also been shown to exclude women’s rights by failing to consider such rights unless a female plaintiff explicitly makes a claim against property in court. In these situations, the customary practice of dividing property among sons can supersede laws on succession (Cầm et al. 2012).

Several factors strongly discourage women from accessing legal services, which in turn affects their ability to exercise their land rights. Lower education and language levels are common barriers, particularly for ethnic minority women, as all formal legal affairs must be conducted in written Vietnamese. Notions of women’s lower social status and perceived inability to interact with formal legal institutions also discourage women from seeking legal assistance. In addition, women have reported factors preventing them from accessing legal services, including a reluctance to deal with complicated bureaucratic processes and a sense of disempowerment when interacting with government representatives (Cầm et al. 2012).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Vietnam’s land policies are administered through a hierarchy of authorities at the central level, across 61 provinces, across more than 500 districts and across more than 10,000 communes (Huyen and Ha 2009).

The country has a unified and decentralized system of state land management and administration set out in the 2003 Law on Land. In addition to establishing systems at all levels, this law concentrated policy formulation and supervision of implementation at the central level and distributed roles among numerous central agencies including the administrations of justice, natural resources, construction, agriculture, finance and planning and investment.

As provided for in the 2003 Law on Land, the state makes decisions on provincial and city land use zoning and planning and exercises uniform administration of land throughout the country. The National Assembly promulgates laws on land, makes decisions regarding national land use zoning and planning and exercises supreme supervision of land administration and use throughout the country. Based on issues presented by the government, the National Assembly’s Standing Committee decides policies regarding land use rights and quotas assigned to family households and individuals (FAO 2012a; GOV Law on Land 2003).

The Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MoNRE) is the primary central-level administrative body for land, water and mineral resources. It is charged with the state administration of land, directing and organizing inspections of land nationwide and directing the surveying, measurement, drawing and management of cadastral maps, land use status maps and land use zoning maps nationwide. In addition, it provides regulations on cadastral files and guidelines on their formulation, revision and management and issues LURCs (FAO 2012a; GOV Law on Land 2003).

Below the central level, provincial and district entities and commune People’s Committees carry out responsibilities for land policy implementation with support from provincial or district departments for Natural Resources and Environment and commune cadastral officers (World Bank 2010b).

People’s Committees at all levels serve as organs of state administration. In provinces and cities, they issue certificates of land use rights to religious organizations and establishments, Vietnamese residing overseas and foreign organizations and individuals; direct the implementation of land use zoning and planning of their locality; and inspect implementation of land use zoning and planning by local authorities of the lower level (FAO 2012a).

People’s Committees at the provincial city (a unit of administration distinct from province or city), district and town levels are responsible for allocating land and issuing land use right certificates to households and individuals, communities of citizens and Vietnamese residing overseas who purchase residential housing attached to residential land. They are also responsible for all procedures of transfer and exchange of land use rights, except in rural areas, where these responsibilities belong to the People’s Committee at the commune level (FAO 2012a).

People’s Committees at the township, ward and commune levels are responsible for settling land disputes which conciliation efforts are unable to solve, and for which legal documents for the disputed land exist. Where documentation is absent or insufficient, such disputes are brought to the city or province-level People’s Committee or, if the parties disagree with the city or province People’s Committee, to the Minister of Natural Resources and Environment for resolution. These also organize and direct implementation of land use zoning and planning of their localities, and identify and prevent land use which is inconsistent with the land use zoning and planning (FAO 2012a; GOV Law on Land 2003).

Land Registration Offices, established in all provinces and a third of districts, provide land-related public services. These offices lack consistent organizational, staffing and service standards as well as the capacity to meet increasing demands from land users (World Bank 2010b).

The Land Inspectorate is charged with inspecting how well state bodies and land users comply with land laws and with preventing and resolving breaches of the law (FAO 2012a).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

As discussed above, land is a scarce resource in Vietnam, which has one of the world’s lowest land endowments on a per capita basis. There is evidence that prices for both rented-in cultivated land and cultivated land obtained by auction have increased significantly since 1997 (World Bank 2010b; Marsh and MacAulay 2006).

The 2003 Law on Land governs the circumstances and conditions under which land-use right holders can sell, lease, sublease or mortgage their rights or assets attached to leased land. Transfers: require the transferor to possess a registered LURC; must be for a period within the term initially granted to the transferor; and cannot involve land under dispute (GOV Law on Land 2003).

The legal status of transferors and transferees (e.g., status as an organization or household, or as a foreign or domestic entity) also constrain the ability to transfer and receive rights. For example, foreign investors cannot buy land-use rights directly from LURC holders and must instead negotiate with the government. The means by which a transferor acquired land-use rights, whether by allocation or lease, also affects the transferability of use rights. In addition, a transferee can only use a land parcel in a way consistent with the use purpose that the state has assigned to that parcel, which is listed on the LURC. Thus, if a parcel has a residential use purpose, the transferee cannot use the land for agriculture, and vice versa. Those wishing to change a parcel’s use purpose must obtain official permission (GOV Law on Land 2003; Marsh and MacAulay 2006).

People’s Committees at the commune level (for rural areas) and at the provincial, district or town levels (for other areas) are responsible for approving transfers and exchanges of land-use rights (Ngo 2005; FAO 2012a; GOV Law on Land 2003).

Data indicate that Vietnam has an active market for land-use rights, though the volume of transactions varies considerably between provinces. The country’s decollectivization of farms in the late 1980s and issuance of LURCs have been identified as having triggered the emergence of land lease and land transfer (chuyen nuong dat) markets (Marsh and MacAulay 2006; Kirk and Tran 2009; Ngo 2005).

Bureaucratic processes may be a limiting force. Research suggests that local state entities play an active role in setting the terms for land transactions in order to prevent poor families from selling their lands, which would subject them to the dynamics of the land market. Such restrictions may have the unintended effect of worsening outcomes for the poor by driving transactions underground and forcing poor sellers to accept less favorable terms (Kirk and Tran 2009).

Specifically with regard to rentals, legal restrictions on lease periods are so constraining as to inhibit leasing. Under the 1993 Land Law, those with use rights cannot lease out their rights for more than three years (Haque and Montesi 1996).

Lack of transparency is a key obstacle to the emergence of a more functional land market. Vietnam has been ranked since 2006 as one of the world’s least transparent real estate markets (World Bank 2010b).

The government’s intervention in the allocation, transfer, use and valuation of land also frustrates the development of a free market in land-use rights. Additionally, the costs associated with registering transfers of land-use rights, time-consuming procedures, rent-seeking behavior in peri-urban areas, and unclear regulations have led to many transfers and use changes occurring illegally (Marsh and MacAulay 2006; World Bank 2010b).

In explaining the difficulty they encounter in purchasing land-use rights, farmers have cited several factors, including: inadequate access to credit; a lack of available land, particularly in northern communes; and a lack of available farm labor (Marsh and MacAulay 2006).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

Vietnam’s policy on compulsory acquisition is laid out in the 2003 Law on Land, which characterizes the state’s acquisition as its “recovery” of the public’s right to land from private users who have exercised use rights to it. Under the 2003 Law on Land, compulsory acquisition is permitted for the following purposes: national defense and security; national interest; public interest; and economic development. Economic development is defined as “cases of investment in construction of industrial zones, high-tech zones, economic zones and large investment projects as stipulated by the Government.” The law also establishes the procedures the state must observe (including the procedure for assessing the price of land to be taken) and sets out the rights and obligations of households, individuals, domestic economic organizations and foreign investors in the compulsory acquisition process (GOV Law on Land 2003, Art. 40; World Bank 2011a).

Decrees 17, 69, 84, 181, 188 and 197 guide the implementation of the 2003 law. These decrees limit the circumstances under which compulsory recovery is allowed, and address, among other things, land valuation methods and compensation, as well as the state’s obligation to resettle and otherwise provide support for those whose land is taken (World Bank 2011a; CIEM 2006).

Those with rights to land may also face recovery by the state in a variety of other circumstances. If the user dies without an heir, the right is lost and control over the land reverts to the state. If the user misuses the land or violates use terms, the user may lose the right. For example, where land designated for annual crops is not used for 12 consecutive months, the state may determine that the user has forfeited the right (GOV Law on Land 2003).

People’s Committees of districts, provincial cities and towns are responsible for deciding whether to recover land from households, individuals, communities of citizens and certain overseas Vietnamese. In cases involving organizations, religious establishments, foreign entities and certain Vietnamese residing overseas, these decisions are made by People’s Committees of provinces and cities (GOV Law on Land 2003).

By law, compensation for recovered land must correspond with market price. In practice, however, there are no specific procedures for assessing market value, and provincial People’s Committees determine land prices. Households and individuals whose agricultural land is recovered are entitled to compensation in the form of land that has the same use purpose, or, if no such land is available, to a cash amount equaling the price of land with the same purpose (World Bank 2011a; GOV Decree 69/2009/ND-CP 2009a).

In addition to addressing the matter of compensation, the 2003 Law on Land requires provincial and district People’s Committees to give notice to parties facing land recovery, and provides that those losing their land have the right to make a complaint against a decision for recovery (GOV Law on Land 2003).

The most common type of recovery case involves the state’s acquisition of land from farming households for the development of industrial zones and clusters. By 2005, the state had taken land from over 100,000 households for the development of more than 190 industrial zones and clusters. Although the conversion of land – including agricultural land – is an important source of land supply for the private sector, conversions have been criticized for their adverse impact on poor households in rural and peri-urban areas. Such impacts include livelihood disruption, social and cultural dislocation and negative impacts on food security arising from large-scale conversions of paddy land to other uses (CIEM 2006).

Vietnam’s current procedures for recovery and reallocation are said to be slow, unpredictable and lacking in transparency. Administrative complaints regarding land account for 70% of complaints and disputes that are directed toward the government each year, and 70% of these relate to compensation and resettlement. Widespread hostility surrounds the issue of compensation, and, in some cases, violence has erupted as a result of disputes. Reasons behind this hostility include: the fact that authorities use subjective approaches to determine land values, which they often set below market rate without consulting displaced households; that land users are compensated on the basis of their existing use, rather than for the increased value that will result from the conversion of their land; that valuations vary across administrative boundaries, which can mean different rates are applied to adjacent plots; and disputes over plot measurements, which sometimes differ from measurements in land records (World Bank 2010b; CIEM 2006).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

The state’s introduction of private use rights in 1993 led to conflicts with numerous ethnic communities. The new model of individual use rights tied to specific land parcels did not apply easily to minority group land-use practices, which tend to rely on shifting cultivation and forestry. Some communities, preferring to maintain traditional collective management systems, refused to accept individual land-use certificates and the privatization of use rights. Conflicts were particularly severe in the central highlands, where national army and police forces deployed in 2001 and 2003 to quell protests by thousands of ethnic minority people (Ravallion and van de Walle 2008; Andersen 2011).

Perhaps in response to the unrest, the 2003 Law on Land provides for a kind of communal tenure by recognizing that the state may allocate land to a “community of citizens.” Although this means it is now legally possible to institutionalize communal land tenure, institutionalization has not occurred in practice, and the potential for conflict remains (Andersen 2011).

Conflict also surrounds the competing demands of various groups for agricultural land and forestland. Ethnic minorities, local farmers and forest dwellers, recent migrants and state forest enterprises often have conflicting interests. However, processes for resolving them in an economically, socially and environmentally sound way have not yet been developed. Conflicts have been rife in parts of the central highlands, which have seen particularly large population in-migration. Between 1976 and 2001, the population more than tripled in the central highlands as mostly lowland Kinh (Vietnam’s ethnic majority group) migrated to the area and occupied communal land occupied by ethnic minorities (World Bank 2010b; Writenet 2006; Andersen 2011).

The growing coffee industry brought many newcomers to the central highlands area in the 1980s and 1990s. Between 1976 and 1996, Dak Lak province received 311,000 migrants (many of them ethnic minorities), a number exceeding the area’s entire indigenous population. Conflict has arisen as locals are pushed from their lands and as migrants clear forestland, fallowing swidden lands or community fields that appear to be unoccupied (Writenet 2006).

The number of large-scale land disputes has increased since the beginning of 2012. Among these disputes are numerous high-profile conflicts relating to compulsory acquisition. As discussed above, compensation for expropriated land often falls below market price despite legal requirements. Disputes over compensation sometimes result in violence. By law, district-level officials have the authority to forcibly evict land users who refuse to relocate; there have been a string of forced evictions in rural areas, in some cases involving military forces (Hiebert 2012; CIEM 2006; Ravallion and van de Walle 2008).

In April 2012, authorities in Van Giang deployed 3000 police to pacify approximately 1000 villagers protesting inadequate compensation and consultation relating to a development project. This situation and others involving claims of inadequate compensation for expropriated land have been referred to as “land grabs” (Hiebert 2012; Tran 2006; Radio Free Asia 2012).

Mediation groups, which operate at the street and village level, and mediation committees, which operate at the commune and neighborhood level, play an important role in adjudicating property disputes between individuals. Both are comprised of influential community members. Committees typically include officials from the justice department, the police and the country’s Fatherland Front, and representatives from groups such as the farmers’ union, women’s union, Veterans’ Association and the Communist Youth Union. Although individuals on these committees do not formally act as state representatives, the state is invested in the committees as a matter of policy, and views them as important institutions for handling small disputes. The 2003 Law on Land states explicitly that the “State encourages parties to a land dispute to conciliate by themselves or to resolve the land dispute by conciliation at the grass-roots level” (GOV Law on Land 2003 Art. 135; Cầm et al. 2012).

Mediation committees often prevent women from realizing their land rights, as they tend to resolve disputes according to custom rather than law, particularly in areas where patrilineal groups dominate. While committee decisions are not binding, and complainants may pursue their claims through the formal legal system as well, those who use the mediation process face significant pressure from their community and the committees to end their grievance at the committee level (Cầm et al. 2012).

According to the 2003 Law on Land, parties who fail to resolve their land disputes through conciliation are to refer their complaints to the People’s Committee of the commune, ward or township where their land is situated. If a dispute continues past that point, the committee will refer parties to one of several places – a people’s court, a People’s Committee at a province or city level or the Minister of Natural Resources and Environment – depending on the details of the case (GOV Law on Land 2003).

Parties with complaints about administrative decisions made by People’s Committees can bring their complaint before various levels of People’s Committees and in some cases to People’s Courts (GOV Law on Land 2003).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

The World Bank and AusAid are currently funding a five-year Land Administration Project aimed at improving the quality and timeliness of land-use administration and increasing access to land information services. The project, which MoNRE is implementing in nine provinces, intends to accomplish the following: modernize land administration and information systems; raise public awareness about land administration and certification; and increase public participation in the land-use rights certification process, especially for ethnic minorities. It also involves issuing or re-issuing LURCs through a streamlined application process. As of June 2012, over 500,000 LURCs had been issued under the project (World Bank 2011b; World Bank 2012b; World Bank 2012e).

USAID and other donors have focused projects on improving conditions for ethnic minorities, the rural poor and other marginalized communities. USAID’s efforts related to land include improving access to agriculture extension services and increasing education on horticulture and animal husbandry. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) is currently funding projects to improve rural infrastructure, including irrigation systems and access infrastructures in the central highlands, and to resettle ethnic minorities displaced by a hydropower project (USAID Vietnam 2012; ADB 2012a; ADB 2012b).