Azzedine Alaïa and Cristóbal Balenciaga: The Quest for the Perfect Cut | Bonjour Paris

It was 2017 and Azzedine Alaïa, the revered Franco-Tunisian designer, had just passed away. Hubert de Givenchy, Audrey Hepburn’s favorite fashion designer, approached Carla Sozzani, in charge of managing Alaïa’s legacy via his eponymous foundation, to suggest an exhibition showcasing the incredible collection of Cristóbal Balenciaga’s couture creations, comprising more than 400 pieces, that Alaïa had amassed. Givenchy, himself one of Balenciaga’s protégés, would unfortunately not live to see the show become reality today, as he died just a few months after his meeting with Sozzani. The Association Azzedine Alaïa and Olivier Saillard, former director of Palais Galliera-Musée de la Mode de Paris, have capitalized on his intuition by putting together a show that reveals how inextricably tied were Alaïa and Balenciaga, despite the fact they never met. The collection began by chance in 1968, with a phone call by Madame Renée, the première who ran the Balenciaga house with military precision. The Spanish maestro was retiring, but there were gowns and fabric left at the atelier, and she did not want to waste his creative genius by throwing them away. Would Alaïa be interested in purchasing them for a token price? Balenciaga’s career had started in the 1930s, when he moved to Paris from his native Guetaria, in Spain. Within a short period of time, his incredible skill would garner him a cult-like following, clients even braving the risks of the war to come order their couture gowns to Paris. His clientele comprised heiresses and royals, all willing to sit in religious silence during his two-hour shows, furiously jotting down the numbers of each of the pieces they wanted to order. It is rumored that John Fitzgerald Kennedy balked at the bills for the gowns Jackie wanted to purchase, and that it was her father in law who finally footed the bill, and not the US taxpayer. He was a secretive man who shunned publicity, even refusing to appear at the end of his défilés, preferring to watch them from behind the scenes. By the end of the 1960s, the increasingly commercial nature of his trade finally pushed him to give up and close his business down. Over the years his work had acquired such mythical status, not just amongst his clients (American heiress Mona Bismarck is said to have spent three days without leaving her bed upon learning the Maison was closing down) but also in the eyes of fellow designers, including young Alaïa. It was obvious Alaïa could not pass on the opportunity of acquiring what was left at the atelier. Alaïa had moved to Paris from his native Tunisia a few years before, in 1956. After a brief stint at Dior, under the direction of Yves Saint Laurent , the young designer was introduced to the cream of Parisian high society, and started designing clothes for a restricted circle of wealthy patrons, that he would welcome to his own apartment. What this exhibition brings to life is how Balenciaga nurtured Azzedine’s inspiration. Beyond diaphanous screens, which give the show a dream-like feeling, the visitor discovers skillful duets of clothes, one by each designer. Besides the evident structural differences — the Spanish master’s gowns are architectural constructions with daring forms, barely touching the body, while Alaïa’s resemble body-con armors– so many other details — their shared passion for the color black, requiring the cut to be perfect– are so similar that the difference in time seems to vanish. As I explore the show, I bump into a group of students in their 20s. If their creative attire were not enough, the topic of their studies is betrayed by the way they look at the clothes, their hands itching to touch them and find out how they have been put together. This seems to be the most fitting tribute to Alaïa: The transmission of knowledge to a younger generation of fashion dressmakers, whom he thought would benefit from learning the techniques and the inspiration beyond the creations of their elders, was always at the center of his endeavor as a collector. “Alaïa and Balenciaga: Sculptors of Form” is on at the Association Azzeine Alaïa , located at 18 Rue de la Verrerie in the 4th arrondissement, until June 28, 2020. The exhibition is open every day from 11am to 7pm. Love Paris as much as we do? Get some more Paris inspiration by following our Instagram page.

• If this is the first time you are logging in please CLICK HERE to create your password.

It was 2017 and Azzedine Alaïa, the revered Franco-Tunisian designer, had just passed away. Hubert de Givenchy, Audrey Hepburn’s favorite fashion designer, approached Carla Sozzani, in charge of managing Alaïa’s legacy via his eponymous foundation, to suggest an exhibition showcasing the incredible collection of Cristóbal Balenciaga’s couture creations, comprising more than 400 pieces, that Alaïa had amassed.

Givenchy, himself one of Balenciaga’s protégés, would unfortunately not live to see the show become reality today, as he died just a few months after his meeting with Sozzani. The Association Azzedine Alaïa and Olivier Saillard, former director of Palais Galliera-Musée de la Mode de Paris, have capitalized on his intuition by putting together a show that reveals how inextricably tied were Alaïa and Balenciaga, despite the fact they never met.

The collection began by chance in 1968, with a phone call by Madame Renée, the première who ran the Balenciaga house with military precision. The Spanish maestro was retiring, but there were gowns and fabric left at the atelier, and she did not want to waste his creative genius by throwing them away. Would Alaïa be interested in purchasing them for a token price?

Balenciaga’s career had started in the 1930s, when he moved to Paris from his native Guetaria, in Spain. Within a short period of time, his incredible skill would garner him a cult-like following, clients even braving the risks of the war to come order their couture gowns to Paris. His clientele comprised heiresses and royals, all willing to sit in religious silence during his two-hour shows, furiously jotting down the numbers of each of the pieces they wanted to order. It is rumored that John Fitzgerald Kennedy balked at the bills for the gowns Jackie wanted to purchase, and that it was her father in law who finally footed the bill, and not the US taxpayer.

He was a secretive man who shunned publicity, even refusing to appear at the end of his défilés, preferring to watch them from behind the scenes. By the end of the 1960s, the increasingly commercial nature of his trade finally pushed him to give up and close his business down.

Over the years his work had acquired such mythical status, not just amongst his clients (American heiress Mona Bismarck is said to have spent three days without leaving her bed upon learning the Maison was closing down) but also in the eyes of fellow designers, including young Alaïa. It was obvious Alaïa could not pass on the opportunity of acquiring what was left at the atelier.

Alaïa had moved to Paris from his native Tunisia a few years before, in 1956. After a brief stint at Dior, under the direction of Yves Saint Laurent, the young designer was introduced to the cream of Parisian high society, and started designing clothes for a restricted circle of wealthy patrons, that he would welcome to his own apartment.

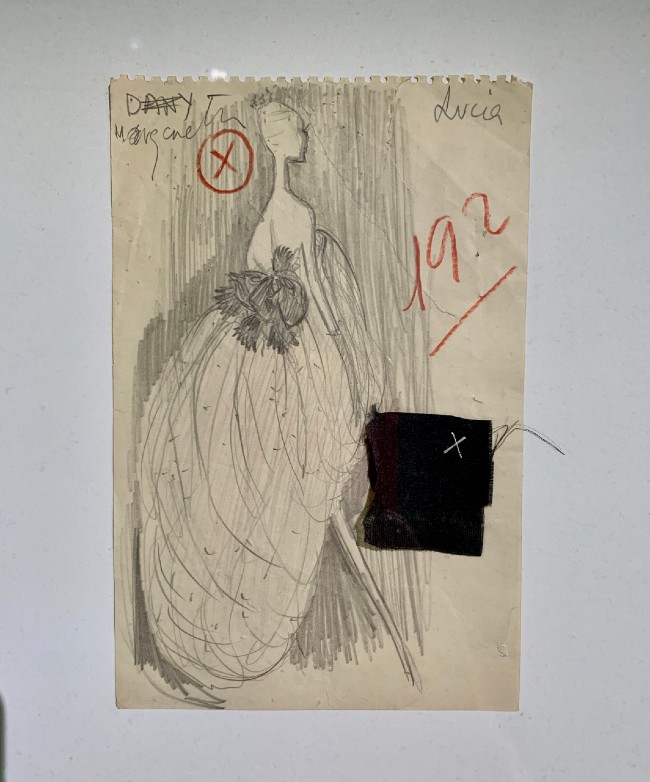

What this exhibition brings to life is how Balenciaga nurtured Azzedine’s inspiration. Beyond diaphanous screens, which give the show a dream-like feeling, the visitor discovers skillful duets of clothes, one by each designer. Besides the evident structural differences — the Spanish master’s gowns are architectural constructions with daring forms, barely touching the body, while Alaïa’s resemble body-con armors– so many other details — their shared passion for the color black, requiring the cut to be perfect– are so similar that the difference in time seems to vanish.

As I explore the show, I bump into a group of students in their 20s. If their creative attire were not enough, the topic of their studies is betrayed by the way they look at the clothes, their hands itching to touch them and find out how they have been put together. This seems to be the most fitting tribute to Alaïa: The transmission of knowledge to a younger generation of fashion dressmakers, whom he thought would benefit from learning the techniques and the inspiration beyond the creations of their elders, was always at the center of his endeavor as a collector.

“Alaïa and Balenciaga: Sculptors of Form” is on at the Association Azzeine Alaïa, located at 18 Rue de la Verrerie in the 4th arrondissement, until June 28, 2020. The exhibition is open every day from 11am to 7pm.

Love Paris as much as we do? Get some more Paris inspiration by following our Instagram page.