Calvin Klein Brand History: Everything You Need to Know

Calvin Klein is still an enigma. Yes, we’re aware of his underwear and his fragrance, but how he got to that point is still something of a mystery. Klein has re-entered the public sphere lately, giving a series of interviews about the brand he sold to Phillips-Van Heusen Corp in December 2002.

Klein graduated from the High School of Industrial Arts and in the fall of 1960, started at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT). His first full job in fashion was in 1961, when he took on a copyboy role in the art department at WWD. In January 1963, he graduated from FIT with a Fine Arts degree. His first job after graduating was working for a company that specialized in making dresses out of a fabric called “whipped cream.” Dissatisfied, after three months Klein asked for a hundred-dollar raise and when his boss declined, he quit.

He soon took on a role at coat manufacturer Dan Millstein, working as a sketcher. Of the role, Klein said “I learned a lot, because he threw me into the snake pit.” Millstein took Klein to the Paris haute couture shows, using Klein to copy the clothes they saw at the shows.

Despite the perks of attending Paris Fashion Week, Millstein was known as a volatile and difficult boss and Klein soon made plans to leave. He was soon recommended for a role at at Halldon Ltd, a manufacturer which specialized in fake-fur outerwear. It was this work that got him his first mention in the press, being included in Tobe Report in April 1967.

However, he soon tired of this role as well. He got in contact with an old friend from Dan Millstein, Abe Morenstein, who also wanted to start his own business. Morenstein worked out that they needed $25,000 to set up the business properly. The two tried and failed to raise capital on Seventh Avenue but, when Klein was considering giving up, his childhood friend Barry Schwartz gave them $2,000, enough to get samples made. Klein gradually began using Schwartz’s finances regularly, although Morenstein claimed that Klein never said where he got the money from.

After creating a collection with Klein, Morenstein wanted to incorporate a company with Klein and become official partners. But Klein, then 25, had already incorporated a company, Calvin Klein Ltd, using Barry Schwartz as a partner and leaving Morenstein out. This was officially set up on December 28, 1967, although, according to Morenstein, Klein didn’t tell him this until early 1968. Morenstein and Klein didn’t speak again for 24 years.

Calvin Klein the Brand

Klein’s first stockist was by luck. Donald O’Brien, then vice-president of Bonwit Teller, was on his way to a different appointment when he happened to see one of Klein’s coats hanging on his studio door and made an impromptu visit. O’Brien then invited Mildred Custin, who Klein called “the grand dame of the retail world.”

Custin made a sizable order and doors continued to open after this, especially after Bonwit Teller took out full page advertisements showing off Klein’s wares in The New York Times. Soon, Bergdorf Goodman and Saks would place orders, leaving Calvin Klein Ltd to gross a million dollars in its first year of business. As the company grew, Klein decided to move his offices into the building where his former employer Dan Millstein was based in an attempt to rub his old boss’s face in his newfound success.

This success led Klein to hold his first fashion show in April 1970. The show was modest, costing around $10,000 dollars to produce. The show was deemed a huge success, with WWD saying in their report that “In just 50 pieces, Calvin Klein joins SA’s [Seventh Avenue’s] Big Names as a designer to watch.” Klein was also seen as, in WWD’s words, “the fashion answer to this season’s rising prices.”

By 1971, Klein was a success story, with volume at $5 million. Later on, needing to expand even further, Klein took over his old boss’s Dan Millstein’s space as that company suffered. Millstein had intentionally quoted an overpriced figure to put off Klein, but Klein paid the amount and bought several objects in the office that were there back when Klein was an employee. He also took over Millstein’s actual office space.

In 1973, he won his first Coty American Fashion Critics award. Next year, he won the award for the second time in a row. By 1975, revenues were at $17 million and Klein had been voted into the Coty Hall of Fame. At 33, he was the youngest designer to achieve this. By 1976, Klein’s licensing deals alone made the company $6 million. The company hired Hermine Mariaux, a former director of Valentino in America, to oversee the roster of licensees.

In contrast to Pierre Cardin, Klein cultivated his roster of licensees very carefully. Alixandre Furs, the famous fur company, was Klein’s first licensee. At that time the only other licensees were Hubert de Givenchy and Viola Sylbert. Another of his first deals was with Japanese department store Isetan, who reproduced every Klein item and recut it to fit a smaller customer. In 1977, Klein also embarked on launching menswear. The menswear was backed by Maurice Bidermann, who signed a five-year licensing deal to launch Calvin Klein Menswear Inc.

The next step for Klein was to launch his own fragrance. While many licensing companies had asked Klein, none wanted to cede to Klein’s demands for total control over the product. The only company that came close to securing a deal was Revlon. Klein and Stanley Kohlenberg, then domestic president of Revlon’s Group III, had several meetings about a possible fragrance but nothing came to fruition.

Klein decided to do something unheard of at the time, and put up his own money to fund his fragrance. He then hired Stanley Kohlenberg, announcing the hire in January 28, 1977’s edition of WWD. Kohlenberg, who hadn’t yet told his boss, was escorted out of the Revlon premises and started working for Klein on February 1.

Calvin Klein in the ‘80s

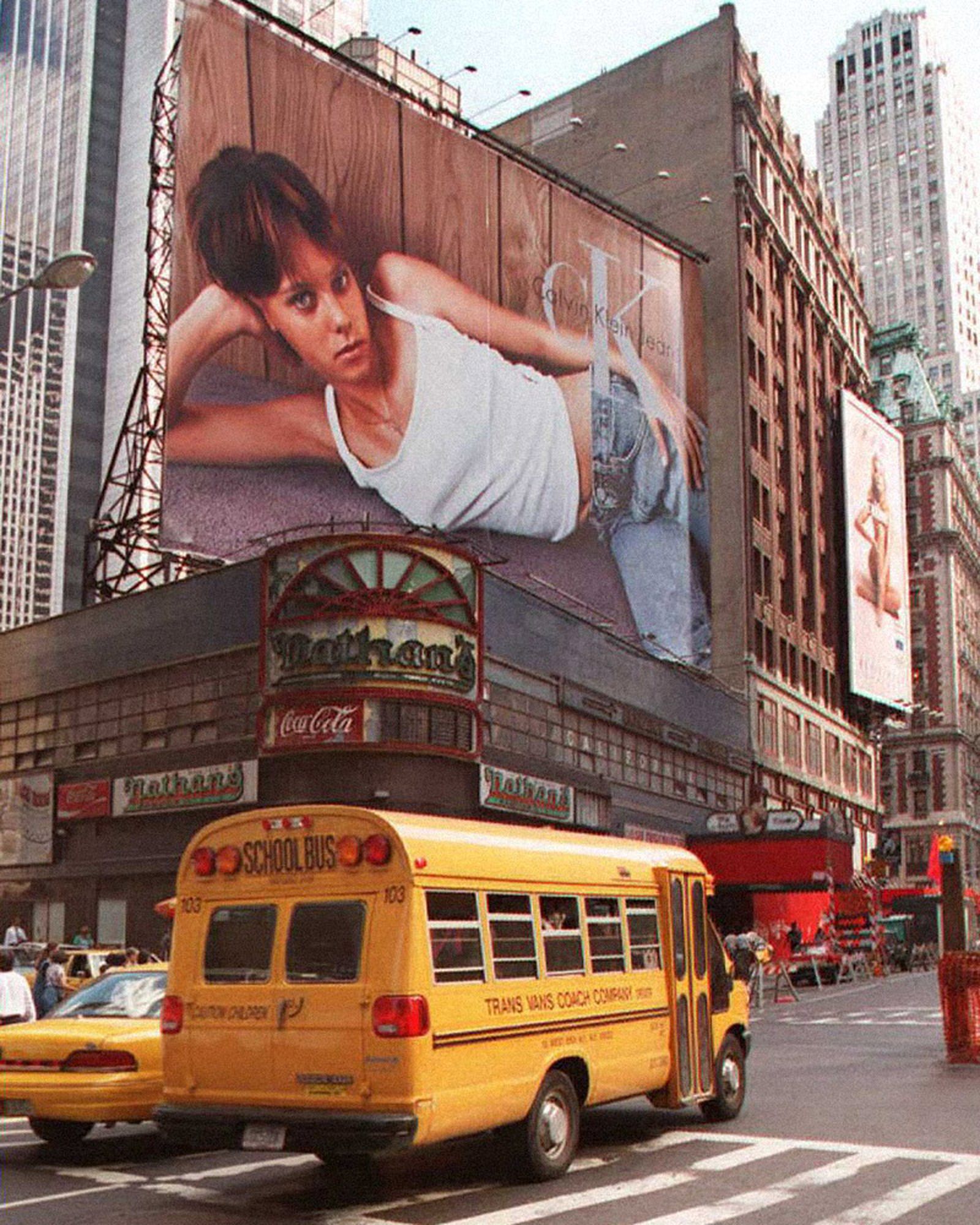

Klein was a famous designer in the ‘70s. But it wasn’t until the ‘80s that the Calvin Klein we know of today emerged. Unlike most designers, Klein’s most famous acts were usually his advertisements instead of any one piece of clothing. In early 1978, Calvin worked with Charles Tracy, then most known as the house photographer for Saks Fifth Avenue, and assigned him a test shoot with Patti Hansen. Klein apparently hadn’t expected to hire Tracy for the shoot, neglecting to send an art director but the results that came back surprised Klein so much he ended up using a shot for the billboard after all. The advertisement was so popular that it remained in the same spot for two years.

Klein had initially been against advertisements on TV, but changed his mind in 1980. He chose Richard Avedon to direct the spots, and Avedon brought on 15-year-old Brooke Shields, who he’d just shot for Vogue. Avedon said that the idea of the TV spot was to “lend the Calvin Klein image to jeans and not a jeans image to Calvin Klein.”

The commercials were created with copywriter Doon Arbus, who wrote the script for the 12 spots. The advertisement that got the most negative reaction was the spot where a 15-year-old Shields says the phrase “do you know what comes between me and my Calvins? Nothing.” The negative call-ins led to KNXT, a Los Angeles affiliate of CBS to put four spots on hold. Then KGO-TV, an NBC affiliate followed. Then WNBC banned several spots, while others moved the commercials to late-night slots. But all the controversy only helped the brand. Royalties received jumped from $1.2 million in 1978 to $12.5 million in 1980.

Getty Images / JON LEVY/AFP

This was all for Calvin Klein Jeans, which was still owned by Puritans. In 1980, Calvin Klein had bout seven percent of Puritan stock, with Klein representing 40% of Puritans’ overall income. By 1982, Calvin Klein jeans was responsible for 95% of Puritans volume. And, as this was a licensing deal, Klein only received $15 million while Puritans received $250 million.

Carl Rosen, the president of Puritans, was diagnosed with bladder cancer and given a year to live. Rosen then made his son, 26-year-old Andrew Rosen chief operating officer and president. When Carl Rosen passed on August 8, 1983, Andrew Rosen took over control of the company. At this time, Calvin Klein and Barry Schwartz started up Calvin Klein Acquisitions specifically for the purpose of a merge of Puritans. Over the next two quarters, Puritans lost substantial amounts, dropping 60% in the fourth quarter of the year. This drop allowed Klein to convince the board to sell the company to Calvin Klein Acquisitions in 1984. While this was happening, Klein also planned his next product that would come to define the brand.

In 1982, Klein decided to go into underwear. To announce this, he hired Bruce Weber for a $500,000 advertising campaign. The underwear itself was made by Bidermann, who manufactured for Jockey. The design was of similar ilk to Bidermann but what distinguished them was the waistband with the “Calvin Klein” name repeated throughout. But the commercials really made the products stand out.

The first campaign used Tom Hintinaus, an Olympic pole vaulter. The campaign was placed on Times Square. When Bloomingdale’s New York branch took stock of the briefs, they sold $65,000 worth of them in two weeks and sales for the first year were projected at $4 million. Klein then launched underwear for women, which remained similar to the menswear, down to the fly-front opening. When that launched, 80,000 pairs were sold in 90 days. This line grew so quickly, Klein quickly licensed it to Kayser Roth, then one of the largest manufacturing companies for underwear and hosiery in the world.

Obsession

Cosmetics was one of the areas that didn’t quite work out for Klein. So much so that on December 31, 1979, he decided to close this arm of the business altogether. A month later, Klein received an offer from Robert Taylor, the president of Minnetonka, who’d made $100 million a year by creating a liquid soap with a pump dispenser a year before Proctor & Gamble. On January 30, 1980, Taylor bought the cosmetics part of Klein.

Though Klein’s first fragrance was a success, it had been shuttered when the cosmetics arm closed. He later launched another fragrance which underperformed. It wasn’t until he launched Obsession in 1985 that he became known for fragrances. His second women’s fragrance, an article in WWD from January 1985 reported that Klein was to spend $13 million on the fragrance in the first year, which was three times what had been spent on Calvin, his first fragrance.

Robert Burns, from Minnetonka, said in the feature that Obsession was “the most important thing we’ve ever done.” Calvin himself said that “The name Obsession is big, like a movie poster for this era, I think of everything I’ve ever done, how obsessed I was. Everyone is obsessed in the ’80s. And, of course, the name suggests an obsession with someone. A man obsessed by a woman.” When asked about the fragrance itself, Klein said, “I wanted something direct, sensuous and provocative, which represents the way I feel about women.”

Spending $13 million on advertising, the largest amount they’d ever spent at the time, didn’t hurt and the fragrance was an immediate success. A WWD article from March 1985 noted that Bloomingdale’s sold $2,000 worth of the fragrance the week before it launched and sold $7,000 worth of the fragrance on opening Saturday alone.

Reports soon came in that Obsession was selling in great amounts, aided by Klein doing what Lester Gribetz said he’d do, showing up at a number of stores and giving personal appearances. Obsession was once again pushed by a controversial and suggestive advertisement, shot again by Bruce Weber and this time showcasing several naked bodies intertwined in a hot tub.

The TV commercials, meanwhile, were again created by Richard Avedon and Doon Arbus. There were four spots this time, all revolving about different people obsessing over model Josie Borain. The overall results from these advertisements were sales. WWD reported in April 1985 that Minnetonka’s net rose by 500%, thanks to the Obsession launch.

The success of Obsession led them to create Eternity, which had an even larger launch budget at $18 million. When Eternity launched in August 1988 it became Klein’s most successful fragrance, grossing $35 million by the end of its first year.

The Clothes

While Calvin Klein’s menswear was successful, it wasn’t necessarily seen as innovative. WWD called it, “Pure American Sportswear but done with style,” and this label stuck to his collections. His strength was still his coats, the product he opened the company with. Despite this, his collections didn’t draw much fanfare, with WWD saying in the same April 1985 article, that Klein was “going through an identity crisis.”

At the same time, Puritans, which Klein had bought out with $105 million in bank loans, immediately started losing money. In a May 1985 WWD article, they reported that “The company immediately ran into a slump in the jeans market and in 1984 lost $7,146,000, which wiped out the company’s net worth.” Klein then reached a new bank agreement and Puritans turned profitable at the beginning of 1985, with a reported earning amount of $3 million.

In 1990 the Puritans division (also named Calvin Klein Sport), lost $14.2 million. But the company overall was doing well. By 1991, the company continued to do well in their underwear and fragrance divisions, but the company had mounting longstanding debts against it, which came from the days of the Puritans takeover.

In 1992, the company’s debt up until the date of September 28, 1991 stood for $54.6 million, mostly in the form of junk bonds. If the bonds weren’t settled by September 1 then, according to a may 1992 WWD article, a principal payment for $15.2 million would’ve been due. To avoid this, David Geffen, a longtime friend of Klein, stepped in and bought up Klein’s company debt, wiping the slate clean. At the time Geffen said that, “I’m not going to become a partner [in Calvin Klein]. It’s a pure investment. I bought it because I think it’s a very good investment.”

To view this external content, please click here.

It was this good fortune that allowed Klein to create his newest advertisements showcasing the underwear line. Starring Kate Moss and Mark Wahlberg (then known as Marky Mark), the images showcased Klein’s now signature nose for envelope-pushing controversy.

The TV commercials were directed by Herb Ritts and featured Wahlberg starring in a script he wrote, alongside Kate Moss. In a WWD article from October 1992, Klein said that “We wrote scripts that I thought were great, but Marky said, “That’s not the way I say it.’ He went on to do his own thing, and it’s all him.”

Klein advertised for the first time on MTV, saying that he was, “aiming at a very young audience. It’s really for kids.” The choice of Wahlberg was influenced by David Geffen, who asked Klein about the idea while Klein was showing Geffen a cover of Mark Wahlberg wearing Klein underwear on the cover of Rolling Stone.

While Klein’s collections always sold, he was also continuously accused of being a plagiarist, who watered down European styles for the U.S. market. In a 1993 Washington Post article, Cathy Horyn noted that a cashmere dress of Klein’s “was a good deal more original than Klein’s previous delvings into beige, which is Armani terra firma.” Armani himself said that he first thought he had a window in Saks when he saw Klein’s menswear suiting.

By 1996, accusations of Klein copying other designers were so strong that he faxed over his collection to press when the trends from Milan started emerging. Even then, Robin Givhan said in a Washington Post piece that “one can only wonder if such strenuous denials are the product of a guilty conscience.” In a WWD article, the fashion director of Saks Fifth Avenue said that Klein had taken liberal inspiration from Helmut Lang and Ann Demeulemeester.

In 1995, there was one last advertisement-based controversy. This time a Klein campaign with young, street-cast models in suggestive poses drew ire from conservative groups. A 1995 article from The Columbian reported that Klein was investigated by the Justice Department and their Child Exploitation and Obscenity Section. C.J. Doyle of the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights called the images “cynical, exploitative and immoral.”

The charges against Klein were for sexually exploiting children, of which he could’ve faced criminal prosecution. While he didn’t have to face any charges in the end, Klein decided to withdraw the commercials. Buzzfeed covered the campaign in a 2013 article, entitled The 1995 Calvin Klein Ad Campaign That Was Just Too Creepy.

Klein sells his label

By the end of the 1990s, Klein was in control of his vast empire, with retail presence in the United States, Europe, the Middle East and Asia. In 1999 Klein announced that he and Schwartz were looking for a buyer for his company. At that time ,Calvin Klein Inc made $170 million in sales but pulled in $5 billion in licensing agreements. Klein’s desire to sell the company but still have complete control meant that the sale of the company took nearly three years, selling to Phillips-Van Heusen.

A New York Times article from 2002 reported on the sale, noting that Klein wouldn’t have creative control anymore. Although Bruce Klatsky, then PVH chief executive, did say that “we’d be idiots not to respect his opinions and we’ll absolutely pay attention to what he has to say.” However Klatsky also noted that “In the end, Phillips-Van Heusen will own 100 percent of Calvin Klein Inc.” Klein stayed on board, but without a title. Klein’s recent comments about not approving of Kendall Jenner shows that his word is far from the final one nowadays and it remains to be seen what he’ll think of Raf Simons’ impending collection.