Education in Germany

Mục lục

Introduction: Recent Trends in German Education

One of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany is a greater push for the digitalization of education. Compared with other countries, Germany has been somewhat slow in adopting computer-based learning. The German federal government has promoted “digital competencies” as a central concept in education for several years—as recently as 2019, it committed €5billion euros (US$5.8 billion) for the modernization of its internet infrastructure and the increased supply of digital devices in Germany’s 43,000 schools. However, the abrupt shift in March of 2020 to online education for close to 11 million school students in Europe’s largest country exposed Germany’s lack of readiness for digital learning. The crisis resulted in cascading calls across the political spectrum to rapidly advance the digitalization of schools.

In higher education, similarly, digitalization is now increasingly viewed as a means of academic modernization, as well as a way of boosting the already surging mobility of international students to Germany. While the COVID-19 emergency led to a sharp drop in the number of international students in the country—an estimated 80,000 of them left during the early stages of the pandemic—Germany has emerged as a growing international education hub in recent years. It draws increasing numbers of students from countries like China and India, notably to its English-taught master programs.

To further advance this inflow of international students, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), the country’s designated funding organization for international exchange, recently adopted a strategy of “internationalization through digitalization” that explicitly seeks to promote academic mobility via digital learning platforms and webinars on topics like the writing of research proposals, online language tests, virtual recruitment events, and online portals to match students with academic institutions.

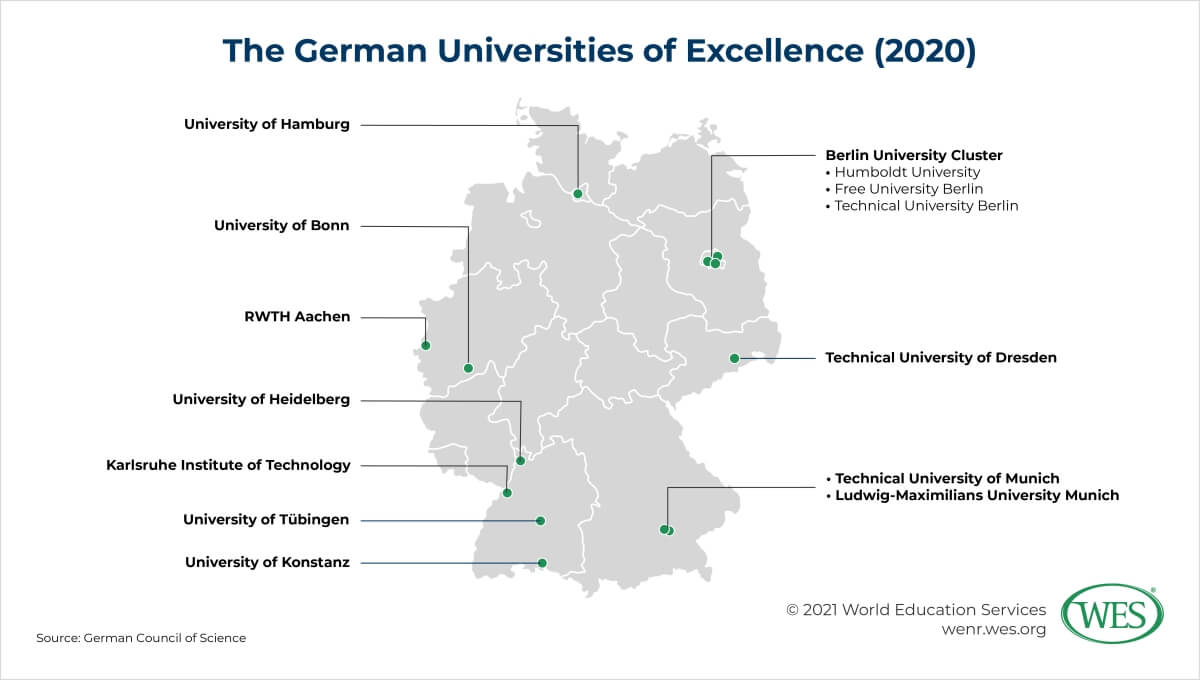

In addition to such digitalization drives, the government continues to systematically promote Germany as an international science hub with large-scale funding projects, such as the so-called Excellence Strategy, which aims at ensuring that German universities are internationally oriented research institutions of global stature. As a rapidly aging society, Germany is in urgent need of immigrants to bridge its mounting shortage of skilled workers. Attracting international researchers and students to its universities is therefore viewed as a critical effort to ensure the inflow of highly skilled immigrants and sustain economic growth.

Another recent concern for German policymakers was the country’s slide in the latest 2018 OECD PISA study. While German students continue to perform above the OECD average, their test scores in reading and natural sciences fell below levels last seen in 2009 and 2006, respectively. Some German officials castigated these results as a “stagnation in mediocrity” and lamented the high number of 15-year-old students—21 percent — who are unable to adequately read or perform mathematical calculations.

However, other observers attribute the mediocre PISA results not so much to shortcomings of the German education system per se, but to the rapid influx of foreign-educated refugees and immigrants, and the difficulties related to integrating these newcomers due to language barriers and academic incompatibilities. Between 2015 and 2016 alone, Germany took in approximately 1.3 million refugees—an influx of historic proportions that resulted in the largest population increase in Germany in years, with most of the new arrivals being young people in need of education.

Given that most refugees don’t speak German on arrival and that Germany has a relatively short history as an immigration country, it thus far managed to incorporate these migrants into educational settings better than expected, despite significant structural and sociocultural barriers. That said, integration problems persist, and the social inclusion of immigrants will likely remain a political issue for the foreseeable future. (For more on this topic, see our related articles on the state of refugee integration in Germany in 2017 and 2019)

International Student Mobility

Until the coronavirus pandemic wreaked havoc on education worldwide, international student mobility to Germany was booming. According to official statistics, the number of international students in the country surged by 46 percent between 2013 and the 2019/20 winter semester, from 282,201 to 411,600. In 2019, 11.7 percent of all students in Germany were international students—a high percentage compared with those of other top destinations like the United States, where just 5.5 percent of all students in 2019 were international, according to the Institute of International Education (IIE). Note, however, that Germany, unlike the IIE, includes in its international student numbers those foreign nationals who are in Germany on immigration or refugee status who attend higher education institutions (HEIs). Even so, 78 percent of all foreign students in Germany—319,000—are international students in the traditional sense, enrolled on temporary student visas.

There were no data for the post-pandemic 2020 summer semester available as of this writing, but it’s clear that the pandemic led to a sharp drop in the number of international students in Germany, as it did in other host countries. According to Uni-assist, Germany’s main credential evaluation agency, for instance, the number of international applications for the winter semester 2020 was down by 20 percent compared with that of the previous year. Interviews of students from India, the second-largest sending country of international students to Germany, reflect that student mobility is currently hampered by concerns about diminished employment prospects after graduation, logistical hurdles, as well as apprehensions about educational quality, given that German universities have since the pandemic switched to blended learning, combining face-to-face instruction with online courses.

That said, interest in studying in Germany among Indian students remains strong overall, and there’s little doubt that Germany will continue to be a dynamic international education hub in the future. The country has a well-articulated and generously funded internationalization strategy that deliberately seeks to attract the world’s “smartest minds.” As noted, Germany has a growing need to import skilled workers. The country already lacks more than 300,000 tech workers—an acute labor shortage that is expected to depress economic growth by 2035.

Against this backdrop, international graduates make for excellent immigrants. They are relatively young and already familiar with the country; they have German academic qualifications and often speak at least some German. Inbound student mobility has consequently been incentivized with changes in immigration policies in recent years that make it easier to work in Germany after graduation and obtain long-term residency. Not only can international students stay and work in the country after graduation for 18 months, but those with adequate employment contracts and German language skills have pathways to long-term work visas and permanent residency.

Language barriers are Germany’s biggest handicap vis-à-vis English-speaking destination countries. However, these barriers are becoming increasingly irrelevant because of the growing availability of English-taught master and doctoral programs. While bachelor programs are still almost exclusively taught in German, international applicants can now choose from more than 1,300 master programs offered in English alone.

What makes these programs highly attractive is the fact that German public universities charge only minimal tuition fees, even for international students—a distinct advantage considering the often-exorbitant costs of study in other international study destinations. No less than 20 percent of all students enrolled in master’s programs in Germany are now international students. In PhD programs, international students even account for 25 percent of all enrollments—a trend that is actively promoted by the German government: 49 percent of all international doctoral students in Germany received public scholarship funding in 2018.

Another draw is Germany’s formidable reputation for world-class programs in engineering and other technical subjects. Fully 42 percent of international students in Germany are enrolled in engineering programs compared with only about 20 percent of international students in the United States. While a majority of international students in the U.S. are enrolled at the undergraduate level, more than 50 percent of degree-seeking students in Germany study in master or doctoral programs. It should be noted, however, that there are variations by type of institutions and country of origin. The number of undergraduate students of African and Middle Eastern origin is significantly higher, for instance.

China has been the largest sending country of international students in Germany over the past decade; it currently accounts for 13 percent of international enrollments in the country. But while the number of Chinese students continues to rise, a more recent development has been the rapid inflow of students from India, which in 2015 overtook Russia as the second most important sending country. Between 2016 and 2019 alone, the number of Indian students in Germany doubled and now amounts to 7 percent of all international students. Given that the most typical international student from India is a graduate student in a STEM discipline with limited financial means, Germany is in many ways an ideal destination for Indian students. The growing availability of English-taught graduate programs and recent changes in immigration laws have made the country all the more attractive for these students.

That said, Syrian students accounted for an even larger spike in new enrollments, with numbers surging by 275 percent over just three years, primarily driven by the massive wave of Syrian refugees who fled to Germany in 2015/16. Although the integration of these predominantly young refugees into the higher education system proved difficult initially, given their lack of German language skills and other factors, attendance rates are now picking up as many of the refugees are progressing through the preparatory programs and language training courses that are required for international students who lack an adequate command of the German language. The number of refugees enrolled at German universities has more than tripled from 9,000 in 2015 to an estimated 30,000 in 2020.

Student inflows from a variety of other countries, including European countries like Austria, Italy, and France, or Middle Eastern countries with long-standing migration ties to Germany, such as Turkey, have been rising robustly as well. However, much larger growth rates were recently seen for countries like Nigeria, Sri Lanka, or Ghana, illustrating that Germany’s international student population is diversifying. If current trends continue, it’s not inconceivable that Germany will eventually replace the United Kingdom as the most important international education hub in Europe, particularly considering the U.K.’s Brexit from the European Union.

Outbound Student Mobility

Germany is not only one of the top five host counties of international degree students worldwide, but simultaneously the third-largest sending country of international degree-seeking students globally after China and India, according to UNESCO data. The latest available German government statistics show that 140,000 Germans studied abroad in 2017, about 90 percent of them in degree programs. This means that there are now twice as many German international students enrolled abroad as at the beginning of the century—a swift increase that was driven, in large part, by the Bologna reforms and the European internationalization paradigm of recent years. Changes like the use of a common European credit system and the splitting of Germany’s long single-tier university degrees into the Bologna two-cycle bachelor and master structure have facilitated international academic articulation and made it easier for Germans to study in other countries. What’s more, German government authorities have made it an official policy goal that 50 percent of all German students acquire some form of study abroad experience.

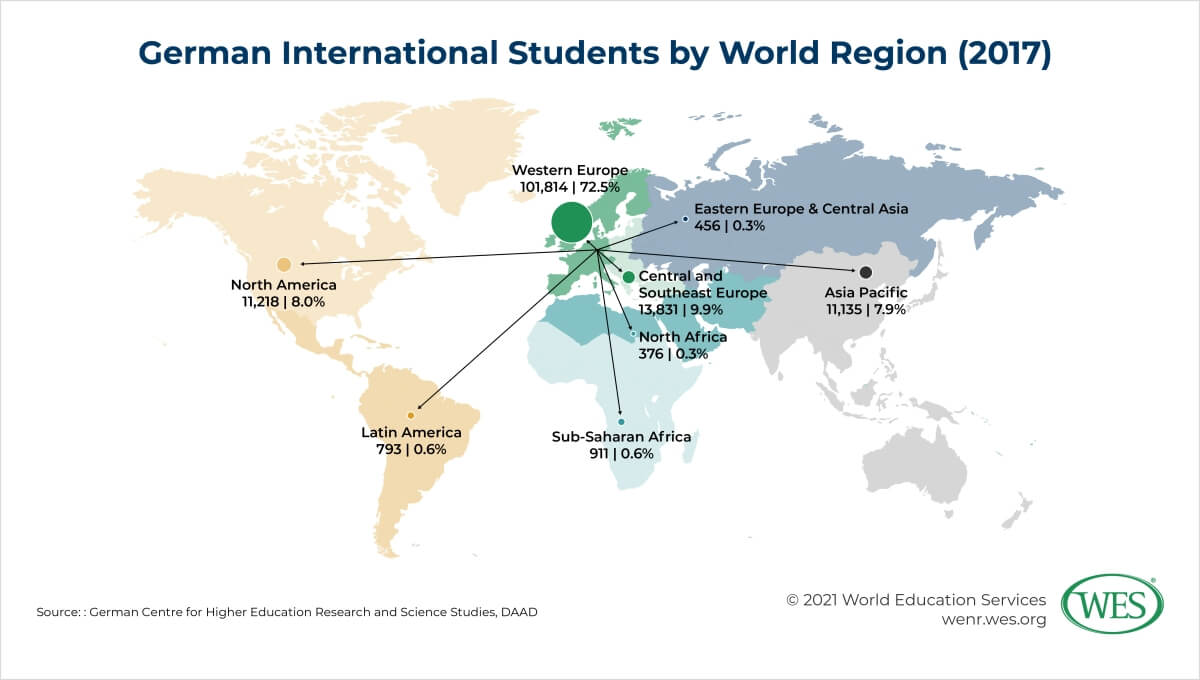

Most German international students—82 percent—currently study in other European countries with Austria, the U.K., the Netherlands, and Switzerland being the top destinations. The next most popular world regions are North America, accounting for 8 percent of overseas enrollments, as well as the Asia-Pacific region, accounting for 7.9 percent of enrollments. The U.S. and China were the fifth and sixth most common host countries of German mobile students in 2017.

Enrollment Trends in the U.S. and Canada

In the U.S., Germany has historically been among the top 20 sending countries of international students after German students started to head Stateside in large numbers beginning in the 1980s and 1990s. But while the number of U.S.-bound students from other sending countries like China and India has surged exponentially since the start of the new millennium, student inflows from Germany have since leveled off and remained mostly flat over the past two decades, ranging from 9,800 in the 1999/2000 academic year to 10,193 in 2014/15, according to IIE. IIE data show that 9,242 Germans studied in the U.S. in 2019/2020—a number that does not yet reflect the fallout from COVID-19. Most Germans were enrolled at the undergraduate level with business and social sciences being the most popular disciplines.

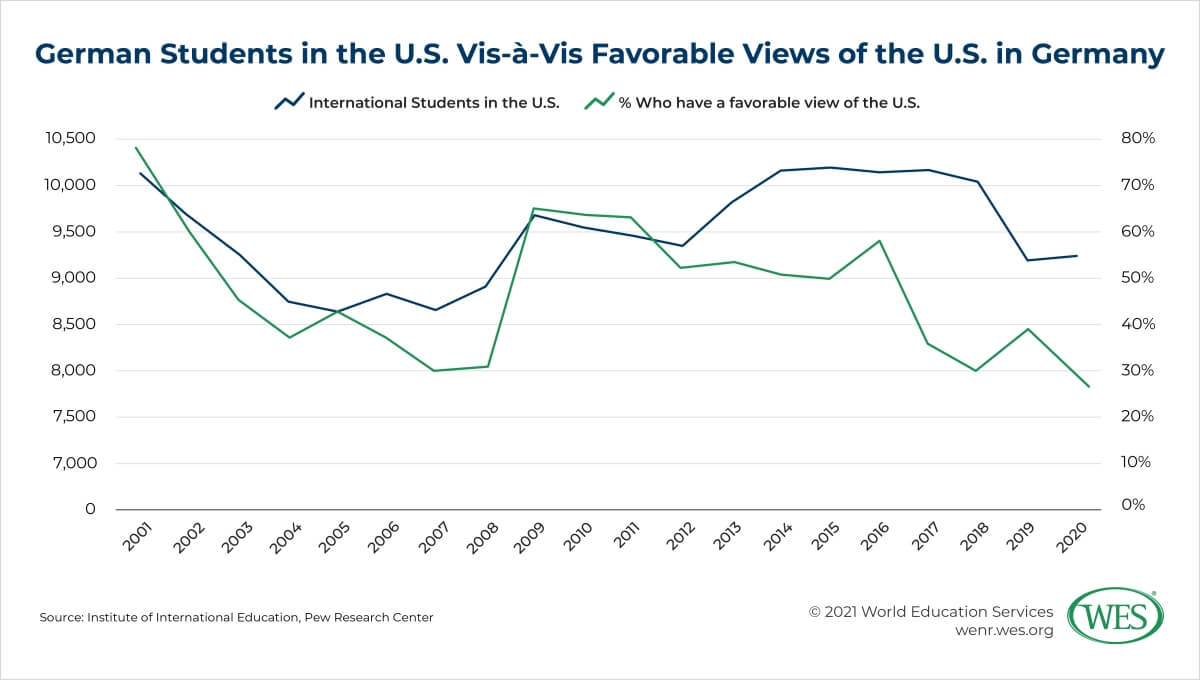

Of note, there was a measurable drop in enrollments by German students in the early to mid-2000s in the wake of the highly unpopular Iraq war. There has also been an apparent downturn in new enrollments during the Trump administration, suggesting that political factors may play a role in affecting student flows from Germany. Opinion polls by the Pew Research Center show that the number of Germans holding favorable views of the U.S. plummeted drastically from 57 percent in 2016 to merely 26 percent in 2020, mirroring a similar decrease in favorable views during the Bush administration.

This shift in attitudes correlates with a significant drop in the number of U.S. student visas held by German nationals over the past four years. Current data provided by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security indicate that the number of active F and M student visas held by Germans declined from 8,787 to 5,866 between December 2018 and September 2020 alone, although much of that decrease is likely attributable to the coronavirus crisis. It remains to be seen how enrollment trends will develop under the Biden administration once the pandemic subsides.

As in the U.S., the number of German students in Canada has been largely stagnant over the past two decades when compared with the rising interest among Germans in pursuing education in European and Asian countries. The overall number of German students in Canada is, in fact, small, amounting to just 2,955 students in 2019, down from a peak of 3,145 in 2008 (according to government statistics).

Transnational Education (TNE)

German HEIs are relative newcomers to providing cross-border higher education. The exporting of academic programs has traditionally been the domain of Anglo-Saxon countries like the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia, which still hold most of the market share. A 2016 study by the British Council found that British HEIs in 2015 offered at least 2,260 TNE programs in 181 countries, with overall TNE enrollments totaling 666,000 students. German universities, by contrast, offered 291 programs in 36 countries, enrolling some 33,000 students, according to the DAAD. Note that these statistics only include government-sponsored initiatives but represent the majority of German TNE ventures.

Aside from these quantitative differences, German TNE is qualitatively distinct in that it is part of a long-term, government-subsidized internationalization strategy, while initiatives in other TNE hubs are often privately led and commercially oriented. Transnational partnerships are not only viewed as beneficial for the global competitiveness of German universities, but also as a tool of development aid, designed to support academic capacity building in other countries. More commercially oriented modes of TNE, such as distance education, validation, and franchising models, remain uncommon in Germany. In fact, the best practices for TNE set forth by the Rector’s Conference, Germany’s university association, stipulate that TNE ventures must be not-for-profit, and that fees can only be charged to cover operating costs. Whereas other TNE qualifications are not necessarily recognized in the countries where students enroll, the “academic qualifications offered by German higher education projects abroad” must be “recognized by both the host country and the participating German universities.”

Through their TNE projects, German universities typically seek to contribute to the modernization of the education system in the host countries. A common model is to partner with universities that remain independent institutions in the home system while being closely associated with and supported by their German “mentor universities.” The largest of these German-backed universities is the German University in Cairo, which enrolled 12,673 students in 2020. Other sizable German-backed universities are located in Oman, Turkey, China, Vietnam, and other countries.

The German Education System

Germany did not exist as a modern nation state until 1871, but education in the German realm has a long tradition. The Kingdom of Prussia is said to be the first country in the world that introduced free and compulsory state-run elementary education in the early 18th century. The first German university, the University of Heidelberg, was established much earlier, in 1386.

However, it is the University of Berlin, founded in 1810, that is often considered to have had the biggest historical impact, at least in hindsight. While some historians argue that its influence has largely been glorified, others regard it as the first modern research university in the world and the model university of the 19th century.

The university was established based on the “Humboldtian model of higher education,” developed by the Prussian philosopher and education minister Wilhelm von Humboldt. Core elements of this model include the integration of teaching and research—which were hitherto largely separated—and an independent academia free from state intervention. Its holistic approach to education, allowing students to freely choose their own course of study, stands in contrast to the more rigid and hierarchical university models prevalent across most of the world in current times. Although some analysts contend that the Humboldtian model has been largely constructed after his death, there’s no question that the model itself has been a central paradigm in German education since the 19th century and has conceptually influenced higher education in much of continental Europe.

That said, the massification of higher education in Germany in the 20th century and other pressures of economic modernization have placed strains on German universities that make it increasingly difficult to maintain the traditional Humboldtian model in practice. While Humboldt’s ideals are still held in high esteem and aspects like university autonomy remain important principles, the Bologna Process, most particularly, has resulted in German universities adopting more “schoolified” and rationalized programs.

The creation of a common higher education area in Europe in 1999, codified in the Bologna declarations, brought radical changes to German higher education, such as the previously unavailable Anglo-Saxon-style bachelor and master programs and the new European ECTS credit system. Whereas students in the 1990s were still able to freely pursue their academic interests and take a broad variety of courses in a more relaxed system without overly stringent semester limits, they are now boxed into more structured programs. Credential evaluators and international admissions officers will find the new programs considerably easier to assess than those of the previous less formal system.

Administration of the Education System

When analyzing German education, it’s important to understand that the country has a federal system of government that grants its member states a high degree of autonomy in education policy—a structure that’s not unlike the federal system of the United States. The German Federal Ministry of Education and Research in Berlin (BMBF) has an important role in areas like funding, financial aid, and the regulation of vocational education and entry requirements in the professions. But most other aspects of education fall under the direct authority of the education ministries of the 16 individual states, called Bundesländer in German.

These states vary considerably in size; they range from the smaller city-states of Berlin, Hamburg, and Bremen to the large state of North Rhine-Westphalia which has a population of about 18 million. Berlin and Hamburg are simultaneously Germany’s biggest cities with 3.8 million and 1.9 million inhabitants, respectively.

Given their autonomy, there can be considerable variation in education from state to state. The length of the secondary school cycle, for instance, varies between 12 and 13 years, depending on the jurisdiction. There are also differences between curricula, types of schools, and so on. However, a coordinating body, the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Culture, facilitates the harmonization of education policies between states.

In higher education, a federal law called the Hochschulrahmengesetz (Higher Education Framework Act) provides an overarching legal framework. In addition, the Conference of University Rectors, which represents most universities, coordinates the development of common norms and standards. What that means in practice is that education laws are similar or consistent in many areas: Academic degrees, vocational and professional qualifications are mutually recognized between the states, so that the system runs smoothly, by and large.

Schools and universities are regulated and funded by the governments of the states (in the case of public institutions). It should be noted, however, that the federal government also provides funding for HEIs, notably in research and development, as well as funding for projects of “supra-regional importance” (such as, for example, the current digitalization effort in schools). Since the state governments are increasingly hard-pressed to support universities amid rising numbers of students, the role of the federal government in higher education funding has expanded significantly in recent years. For example, the government currently subsidizes the states with 19,000 Euros per student to create up to 760.000 additional university seats nationwide over a four-year period.

Universities have a high degree of autonomy and can independently award academic degrees within federal guidelines. That said, final graduation examinations in professional fields like medicine or law are conducted by government authorities of the individual states. The same holds generally true for vocational education, even though the final examinations in this sector are often conducted by government-authorized private industry associations, such as regional Chambers of Industry and Commerce. (Industrie und Handelskammern). Vocational schools fall under the purview of the states, but the federal government oversees on-the-job practical training, which is an integral part of most vocational programs. Important regulations in this sector are codified in a federal law on vocational education (Berufsbildungsgesetz).

Academic Calendar and Language of Instruction

The school year in Germany runs from August to July. While there are some variations between states, it’s generally divided into two terms of 38 to 42 weeks with a winter break in February or March and a longer summer break from July to August or September. At universities, the academic year is split into a winter semester that runs from October to March and a summer semester from April to September. Although each semester is formally six months in duration, classes end several weeks early with the remaining time being dedicated to writing papers and exam preparation, as well as a semester break.

The language of instruction in schools is German. In higher education, the use of English is becoming increasingly common, as noted before. However, while some 13 percent of all master’s programs were taught in English in 2019, undergraduate programs and programs in professional disciplines are predominantly taught in German.

Early Childhood Education

Compulsory education in Germany generally begins at the age of six, but almost all children—95 percent in 2017—attend early childhood education (ECE) between the ages of three and five. This stage is intended to socialize and prepare children for formal education.

Note, however, that there are some minor variations between states. For the most part, ECE institutions are called Kindergartens or “Kitas” (Kindertagestätten) and have few, if any, compulsory curriculum guidelines. But a dwindling number of jurisdictions, such as the state of Hamburg, not only have Kitas, but also maintain an older and more formalized model of pre-school, which is attended for one year only (age five). These pre-schools are usually directly attached to elementary schools.

Also of note, a few states require children who have been attested to have language learning deficits to undergo language training before enrolling in elementary school. In some jurisdictions, older, school-aged children without adequate German language skills, such as children with a migration background, may be mandated to attend ECE language courses as well, even if that means setting back children already enrolled in elementary programs. While these rules are ultimately set by the states, there were political debates in 2019 whether to make ECE language courses mandatory nationwide for all children without sufficient language skills, a change that would predominantly affect migrant children.

Elementary Education

Elementary education is provided free of charge in public school across Germany. While the majority of children in ECE attend private, non-profit institutions, the scope of private education in the formal school system is relatively small, if growing considerably in recent years. Only about 5 percent of elementary students and 9.5 percent of secondary students were enrolled in private institutions in 2017, according to the World Bank.

Elementary education begins at the age of six and lasts four years (grades one to four), except in a small number of states where it lasts six years. Most pupils learn at the Grundschule (foundation school), where they largely study the same general subjects. While there are some variations between state curricula, they usually include German, mathematics, social studies, physical education, technology, music, and religion or ethics. One noticeable difference is the age at which English is introduced. While English classes don’t begin before grade three in some jurisdictions, pupils in some states begin to study English as early as grade one. One state, Saarland, does not offer English in der Grundschule at all. Student assessment and promotion are generally school-based—there are no final graduation exams, nor is a formal final graduation certificate awarded.

The system becomes much more diversified at the end of the elementary foundation cycle, when pupils are assigned to different schools based on their academic ability—a process that can be referred to as “tracking” or “streaming.” The mechanism by which pupils are tracked varies by state. Parents in most states can choose either to send their children to general secondary schools, or to enroll them in university-preparatory schools. In some states, school recommendations influence the tracking. In other states, assignments are mandatory based on grade averages. Reassignments may still occur during an academic “observation phase” in grades five and six.

This tracking process is not as rigid as it once was, and students in the vocational track can cross over to the university-preparatory track at a later stage. Some states have also established more integrated “comprehensive” secondary schools in which students in the different tracks study at the same school. However, deciding which school to attend remains an important factor in the academic career of many students.

Lower-Secondary Education (Sekundarstufe I)

Germany’s secondary school system is complex. There are three main programs, which are studied in different types of schools: Hauptschule, Realschule, and Gymnasium. However, all, or at least two, of these programs may also be offered at the same type of school in some states (such as, for example, comprehensive schools (Gesamtschulen), integrated secondary schools, or combined Haupt and Realschulen). In Bavaria, the Hauptschule may be called Mittelschule (middle school).

Haupt- and Realschule programs are general secondary programs, completion of which satisfies compulsory education requirements, which range from nine years to ten years of education, depending on the state. In addition, these programs generally prepare for vocational upper-secondary education, although transfer into the Gymnasium, which provides university-preparatory education, is possible as well.

Hauptschule and Realschule

Hauptschule programs most commonly last five years (grades five to nine). While there are minor curricular differences between states, nationwide standards exist for several subjects with German, mathematics, and a foreign language (predominantly English) as compulsory subjects in the entire country. In addition, students usually study natural sciences (biology, chemistry, physics, or technology), social sciences (geography, history, politics, economics), as well as physical education, and arts or music.

Progression is based on internal school assessment, but the content of the final graduation examination is usually set by the governments of the states, at least in the subjects of German, mathematics, and English. Upon completion of the program, students receive the Zeugnis des Hauptschulabschlusses (certificate of completion of Hauptschule).

Realschule programs are academically more demanding and take an additional year to complete (grade 10). It’s possible for students who completed Hauptschule to seamlessly transfer into these programs, which generally comprise the same subjects. There are usually centralized state examinations at the end of the program. Students graduate with the Zeugnis des Realschulabschlusses (certificate of completion of Realschule), sometimes also called Mittlere Reife (intermediate maturity).

Both the Haupt- and Realschule credentials provide access to upper-secondary vocational education, but students who only completed Hauptschule traditionally enter programs in more practical trades, whereas Realschule graduates have a wider range of options. Completion of Realschule also allows students to transfer into the university-preparatory track, although they may have to meet certain minimum grade requirements.1

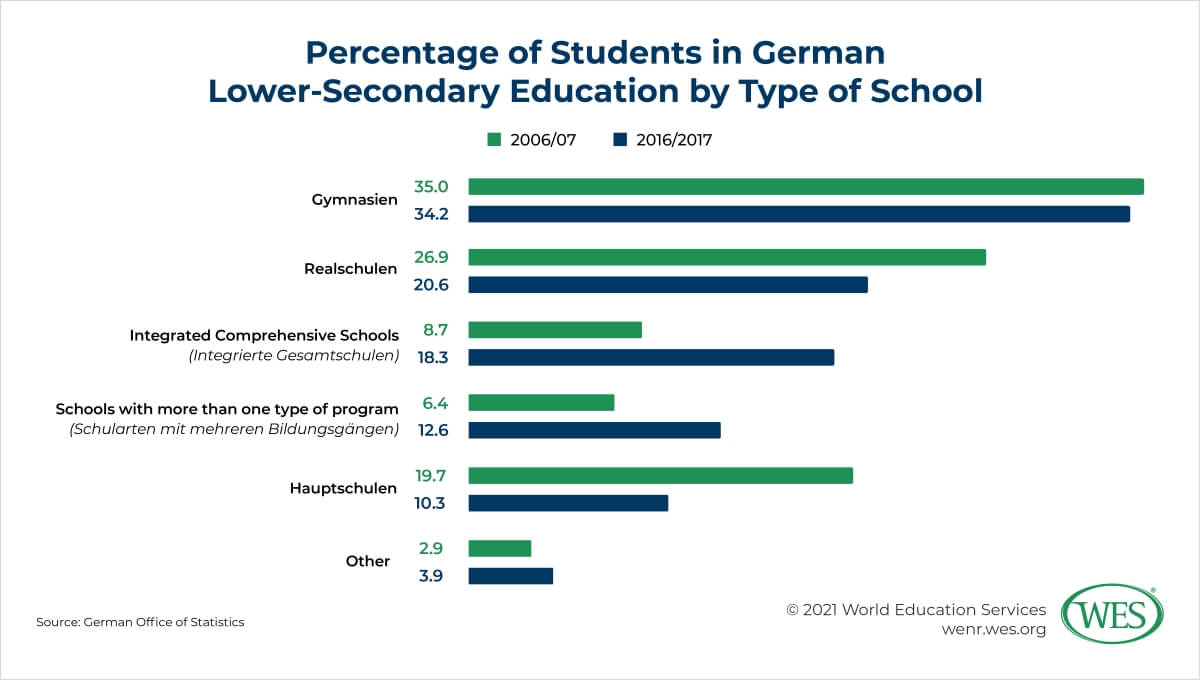

Far more students obtain a Realschule qualification than those leaving school after Hauptschule. The number of students that only complete Hauptschule has drastically declined over the decades. In 1960, 72 percent of all students still attended Hauptschule, or an older type of school of the same level, the Volksschule. In 2017, by contrast, 34 percent attended the Gymansium, 21 percent the Realschule, and only 10 percent the Hauptschule. In general, enrollments are currently shifting strongly in favor of more integrated school forms like comprehensive Gesamtschulen. Between 2007 and 2017, the number of Haupt- and Realschulen in Germany dropped by 45 percent.

University-Preparatory Upper-Secondary Education (Sekundarstufe II)

Upper-secondary education in Germany is called Sekundarstufe II (secondary stage II) and comprises a vocational and a university-preparatory track. The main institution in the university-preparatory track is the Gymnasium, a type of school designed to ensure “maturity” or readiness for higher education. Students who enroll in Gymnasiums after elementary school study largely the same subjects as those in other schools, but they are expected to learn more independently. What’s more, an elective second foreign language is mandatory beginning in grade six or seven (mostly French, Spanish, or Latin, but also Russian, Chinese, or other languages if offered by the school). While there are no centralized graduation exams at the end of the lower-secondary stage, the certificate of completion of grade 10 is usually officially equivalent to completion of Realschule or “middle maturity.”

The length of the upper-secondary stage is either two years (grades 11 and 12) or three years (grades 11 to 13), depending on the state (see the section on upper-secondary school reforms below). In 13-year systems, grade 11 is an introductory stage, followed by a two-year specialization or “qualification phase.” Twelve-year systems begin with the qualification phase, but offer the same curriculum compressed into two years. In some states, the introductory stage is part of the grade 10 curriculum.

In the qualification phase, students can typically choose elective subjects, which they study with greater intensity. These subjects are examined at the end of the program in centralized exams. The concrete combination of subjects, and the name given to them, varies by state: Some have two main subjects studied for five hours a week (Leistungsfächer), and two or three additional examination subjects (Prüfungsfächer). Others have five equally weighted core subjects (Kernfächer) studied for four hours. Yet another variation involves mandatory core subjects (German, mathematics, foreign language) and profile subjects chosen from three different subject areas: arts and languages, science, and social sciences.

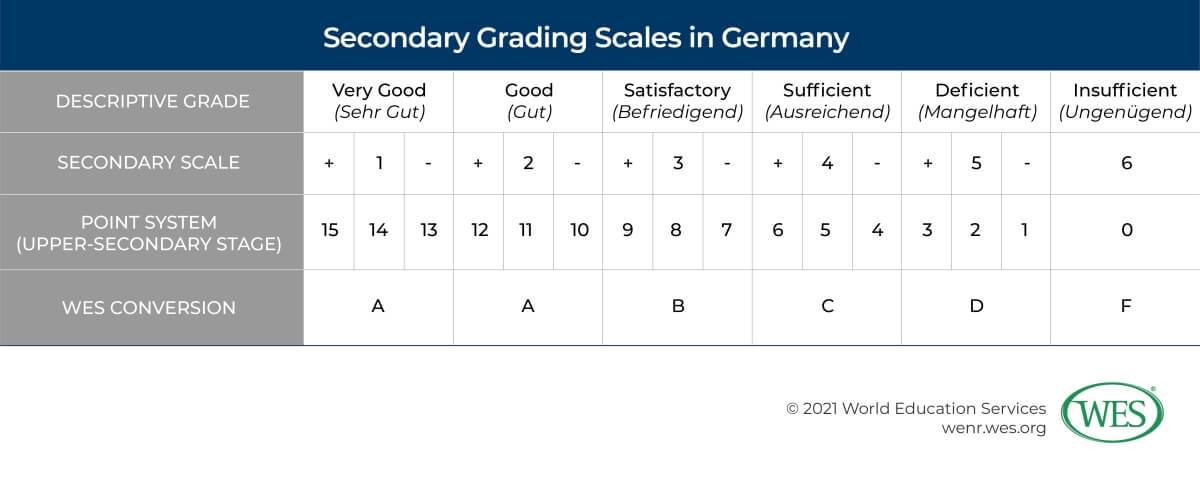

Progression between grades is based on internal school assessment and generally requires examinations. Students who have a failing grade (ungenügend) in a compulsory subject must repeat the year. They can have two conditionally passing grades similar to the U.S. grade of D—the grade of mangelhaft—but must usually repeat the year if they earn these grades in three subjects. The grading scale in the upper-secondary stage at Gymnasiums is a 15-point scale that is different from the grading scale used at other stages and types of schools. Both scales are shown below.

To graduate, students must pass a rigorous written and oral final examination, which is overseen by the ministries of education of the states, almost all of which mandate standard content for one uniform examination taken by all students. To further standardize the exams, several states use the same questions in German, mathematics, English, and French. These questions are developed by the Institute for Educational Quality Improvement (IQB), a joint institution of the states responsible for monitoring the quality of German schools.

The exam is called the Abitur—a name that derives from the Latin verb abire, which can be roughly translated as “to leave.” Students are usually examined in four or five concentration or core subjects. In some states, students may also contribute “special learning achievements,” such as a paper or project, toward their final grade average, which is calculated based on the Abitur exam grades and the regular class grades earned in the final four semesters. The overall grade average is expressed in a range of 1 to 4 with 4.0 being the minimum average required for graduation.

Upon successful completion of the exam, students receive the Zeugnis der allgemeinen Hochschulreife (certificate of general university maturity), a credential that legally entitles graduates to study at a German university. Since higher education in Germany is also mostly free, this may sound like an egalitarian educational utopia. In reality, however, admission to universities can be highly competitive. The final Abitur grade determines how quickly students get admitted into popular programs that have a limited number of available seats (numerus clausus). In medicine, for example, students with lower grades had to wait seven years for admission, on average, as of 2019, because more than 40,000 students applied for 10,000 available seats. (See also the section on university admissions below.)

The Push for the “Turbo Abitur”: A Reform with Mixed Results

Germany has some of the oldest students in the OECD, partially because of the exceptionally long secondary education cycle in many parts of the country. Abitur programs in West Germany had traditionally been 13 years in length, while education in former East Germany lasted 12 years. However, three out of five East German states adopted a 13-year system after reunification, so that by 2000 most states had long programs.

To align these systems with the 12-year paradigm found in most of the world, most German states between 2001 and 2009 began to shorten their Abitur programs by one year to enable students to enter universities and the workforce at a younger age. The drive was called the G8 reforms, referring to a 4+8 system, as opposed to the 13-year G9 system (4+9). To preserve quality standards, the states pledged to maintain the old curricula, but to compress them in the new G8 “Turbo Abitur.”

Yet these reforms soon ran into resistance in various states. The new programs were often more rigid and offered fewer elective subjects, and they required students to spend considerably more time in the classroom per week—changes that proved unpopular with many students and parents. Political opposition mounted with critics lamenting the “lost childhood” of Germany’s students and a loss of educational quality in supposedly overloaded programs. While many education experts disagreed with these notions, the G8 reforms became a political issue and several states reversed course.

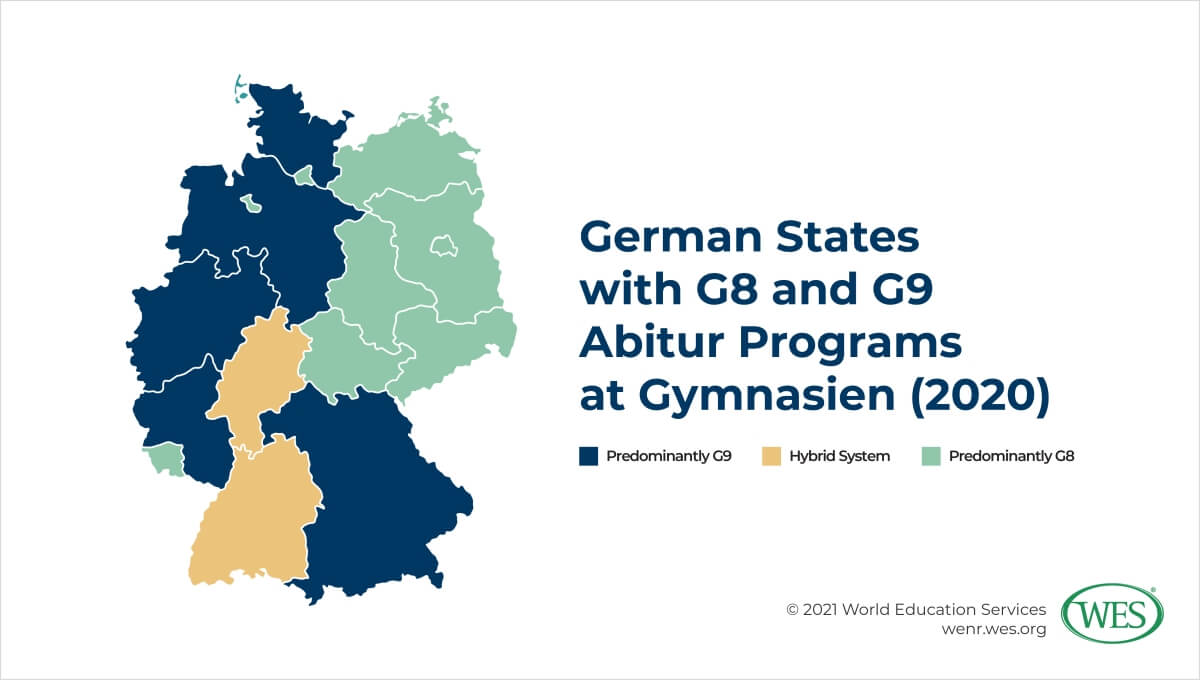

A number of western states have since returned to the G9 across the board. Others now have hybrid systems that allow schools to choose between G8 and G9, while others kept the G8 structure. This has resulted in a rather chaotic patchwork of different systems in Germany. To provide an overview, the most common models in the 16 different states are shown below. In states that are reverting to G9, the G8 programs are gradually being phased out with current students still being able to graduate under the old regulations. (Also note that some G9 states may allow gifted students to graduate after 12 years, but that is not the standard pattern.)

- Baden-Württemberg: Implemented G8 but reintroduced G9 at 44 model schools in 2012

- Bavaria: Decided to switch to G8 in 2004 but returned to G9 in 2018

- Brandenburg: G8 at gymnasiums but students can attend 13-year programs at integrated schools

- Berlin: G8 at gymnasiums but students can attend 13-year programs at integrated schools

- Bremen: G8 at gymnasiums but students can attend G9 programs at other schools (Oberschulen)

- Hamburg: G8 at gymnasiums but students can attend 13-year programs at integrated schools

- Hesse: Gymnasiums can choose between G8 and G9

- Lower Saxony: Returned to G9 in 2015 after initially implementing G8

- Mecklenburg-Vorpommern: G8 (switched from G8 to G9 after reunification, but has since reverted to G8)

- North-Rhine Westphalia: Reverted to G9 in 2019 after initially implementing G8—individual schools may be allowed to continue G8 programs upon special application

- Rhineland-Palatinate: Kept G9, but allows select schools to offer G8 as whole-day programs2

- Saarland: G8 at gymnasiums but students can attend 13-year programs at integrated schools

- Saxony: G8 (kept its 12-year system after reunification)

- Saxony-Anhalt: G8

- Schleswig Holstein: Returned to G9 in 2019 after initially implementing G8

- Thuringia: G8—already had a 12-year system before the reforms; Abitur programs at “vocational gymnasiums” are 13 years in length

Vocational Education

Germany is known for its high-quality vocational education system that has been emulated by several countries worldwide, partially because it’s considered effective in limiting youth unemployment: In 2020, Germany had the lowest youth unemployment rate in the OECD after Japan.

The German system comprises a variety of different vocational programs at the upper-secondary level. Some of these are similar to programs in the university-preparatory track in that students receive full-time classroom instruction. However, the most common form of vocational education has a strong focus on practical training. Depending on the state, between 79 percent and 97 percent of vocational students in 2018 learned in the so-called “dual system” which combines theoretical classroom instruction with practical training in a real-life work environment. Overall, 47 percent of all upper-secondary students were enrolled in vocational programs in 2018—a high ratio by OECD standards.

Students generally enter the dual system after lower-secondary education. The system is characterized by so-called “sandwich programs,” which means that students attend a vocational school on a part-time basis, either in coherent blocks of weeks, or for two or three days each week (at least 12 hours a week, depending on the state). The remainder of the students’ time is devoted to practical training at a work place. Companies participating in these dual programs are obligated to provide training in accordance with national regulations, and to pay students a modest salary.

German law does not stipulate formal academic entry requirements for dual-track programs, but companies can select applicants and set their own requirements. In practice, completion of Hauptschule is therefore often the minimum requirement for programs in crafts and trades, whereas the Realschule certificate or an equivalent Sekundar I qualification is typically required for programs in white collar vocations, such as business, banking, or hotel management. However, it’s possible to enter vocational programs without a formal academic qualification—more than 50,000 students entered programs in fields like sales or machine operations without having a Hauptschule certificate in 2017. On the other hand, a sizable number of Abitur graduates pursue vocational education as well.

About two-thirds of the curricula at vocational schools consists of theoretical instruction in the chosen field, whereas the other third is made up of general education subjects, such as German, social studies, or English. Programs last two to three and a half years, depending on the specialization. Upon completion of the school component, students receive a certificate of completion of vocational school (Abschlusszeugnis der Berufsschule).

Students typically also need to pass a final examination, which may test vocational competencies in addition to theoretical subjects. These exams are conducted by state examination bodies, or state-authorized industry associations like physician’s associations, lawyer’s associations, Chambers of Crafts (Handwerkskammern), or Chambers of Industry and Commerce (Industrie- und Handelskammern-IHK). There are 79 regional IHKs across Germany which conduct examinations in about 250 vocations. The final credential awarded is called the IHK-Prüfungszeugnis (IHK examination certificate).

Credentials awarded in the dual system are formal, government-recognized qualifications. In 2019, there were 325 officially recognized vocations with titles that include carpenter, tax specialist, dental technician, and film and video editor. The most popular field of study among men in 2019 was automotive technology; most women studied office management.

In some regulated vocations, such as allied health fields, an officially recognized qualification is required to work in the field. These occupations are typically regulated at the state level and aren’t part of the dual system. Another difference between the dual system and state-regulated programs is that the latter typically have formal academic admission requirements. Programs in regulated fields such as social work are primarily school-based programs supplemented by internships.

In terms of access to higher education, graduates in the vocational track are generally not eligible for admission into university programs, although they may sometimes be admitted based on special entrance examinations, or completion of a probationary study period, depending on the state. In recent years, regulations have generally been eased to allow more students in the vocational track to enter universities.

It should also be noted that students in many vocational programs may concurrently earn a maturity certificate that provides access to a subset of HEIs—the Universities of Applied Sciences. This credential is called the Zeugnis der Fachhochschulreife (University of Applied Sciences Maturity Certificate). It can be earned at a variety of schools, including vocational schools and gymnasiums in some states. In the latter case, students who don’t meet all the requirements for the Abitur may opt for the Fachhochschulreife. However, these students must also complete a practical internship to earn the final qualification. Programs in the dual system satisfy the mandatory practical training requirement, but students may have to take additional courses in general subjects to meet the academic prerequisites.

Another exit qualification that may be awarded in the vocational track is called the Subject-Specific Maturity Certificate (Zeugnis der fachgebundenen Hochschulreife). Earning this certificate requires less foreign language study. It offers access to Universities of Applied Sciences and a specific set of subjects at universities, such as social science subjects.

Continuing Vocational Education (Berufliche Fort- und Weiterbildungen)

Post-secondary vocational education in Germany is generally less standardized than the upper-secondary vocational programs. One traditional pathway leads to the qualification of “master craftsman” or “master craftswoman” (Meister or Meisterin) in fields like agriculture, engineering technology, or masonry, for instance. Master craftsmen or women can run their own businesses in regulated vocations and train apprentices (journeymen or journeywomen). While many students in this track attend vocational schools, they can also prepare on their own for final examinations that test theoretical knowledge and practical skills, as well as business subjects, law, and vocational pedagogy.

The exams are conducted by chambers of crafts or IHKs. Preparatory programs may last between one and three years with many candidates studying part-time while working. A comparable qualification in business-related fields is Fachwirt (which can be roughly translated as business management specialist). Successful completion of the Meister or Fachwirt examination opens access to university programs in most states.

In addition to these traditional programs, there are a multitude of other part-time education programs that may be as short as three months, or as long as four years, offered by a variety of providers and companies. Students may enroll in these programs to obtain advanced knowledge in their field, improve computer skills, or train in another field. The German government actively promotes further education and lifelong learning, particularly with regard to digital competencies. Retraining programs for unemployed individuals may be paid for by the state, but unlike secondary programs, post-secondary vocational education is usually not tuition free.

Bachelor Professional and Master Professional: Controversial New Qualifications

In January 2020, Germany enacted legislation to further standardize vocational education by introducing new qualification titles. Graduates of initial upper-secondary vocational programs are now categorized under the umbrella term Geprufter Berufspezialist (examined vocational specialist), whereas holders of a Meister or Fachwirt title can now also be awarded the degree of “Bachelor Professional.” In addition, holders of some higher level qualifications like the Geprüfter Betriebswirt (examined business administrator), a title earned upon completion of a post-Meister program, may concurrently be awarded the degree of “Master Professional.” The new titles are pegged at the same levels as academic bachelor and master degrees awarded by universities in the German qualifications framework.

The goal of these reforms is the strengthening of vocational education. Demographic trends and the increased popularity of university education have contributed to a growing skilled worker shortage in Germany. The federal government has therefore argued that the new qualifications—and their placement at the bachelor and master levels—will make the vocational track more attractive to young Germans, as well as enhance the competitiveness of vocational qualifications outside of Germany.

However, these reforms have been sharply criticized, particularly by universities and organizations like the German Association of Engineers. The German Rectors Conference denounced the new degree names as confusing terms that obscure the distinctions between academic and practically oriented vocational education, both of which require different sets of competencies. The president of the conference argued that the new names give the false impression that vocational programs are of academic nature, particularly in other countries, where the degrees of bachelor and master are predominantly reserved for university qualifications. Indeed, the new degree names are likely to confuse some international credential evaluators. It’s the position of World Education Services that the vocational qualifications of Bachelor Professional and Master Professional are not directly comparable with academic degrees awarded by universities in the U.S. and Canadian contexts.

International Schools and Other Special Types of Schools in Germany

International schools are not as prevalent in Germany as in some other countries, and factors like the closure of schools catering to the children of U.S. military personnel due to troop pullouts has affected this sector. According to some tallies, Germany in 2009 had the 7th highest number of international schools worldwide, but was only 19th by this measure in 2019, although most of this shift is owed to the rapid growth of international schools in countries like China, India, and the United Arab Emirates.

In 2019, there were reportedly 177 international schools in Germany, teaching English-language curricula such as the International Baccalaureate (IB), British, or U.S. curricula to some 95,000 students, about 75 of them expat children and a quarter of them German. Most of these schools are expensive private schools with a comparatively small student body. However, there are also some public schools that offer IB programs in addition to regular German programs, enabling students to earn an IB Diploma free of charge. There were 85 IB schools in Germany in 2020. The IB is officially recognized as a university entrance qualification in Germany, as long as students study a certain combination of subjects.

Another type of international school program offered in Germany is the European Baccalaureate, a multilingual program offered by the European Schools that is recognized as a university entrance qualification in all EU member states. There are also several French or bilingual French-German schools that are formally recognized.

Waldorf and Montessori Schools

Germany has the highest number of Waldorf schools in the world (more than 250). Also called Rudolf Steiner schools after the founder of the Waldorf education model, these schools are independent private institutions. They follow a less structured and more holistic pedagogical approach that places greater emphasis on practical and artistic learning than public schools do. While these schools are not supervised by government authorities, they are recognized by the state as special schools. They teach their own curricula, but simultaneously prepare students for official Sekundar I qualifications or the Abitur. However, depending on the state, students must sit for external governmental examinations. In the case of the Abitur, external examinations are required for graduation for students in Waldorf schools in almost all states.

Montessori institutions are another type of independent private school in Germany. There are about 1,000 of them, most of them early childhood education institutions, but there are also various Montessori schools at the secondary level. These schools are officially allowed to operate, but students need to sit for graduation examinations at public schools to obtain an official German qualification. There are also schools that train Montessori teachers. These institutions typically offer shorter diploma courses in conjunction with an official German teaching qualification. (For more information on the Montessori education model, see here).

Tertiary Education

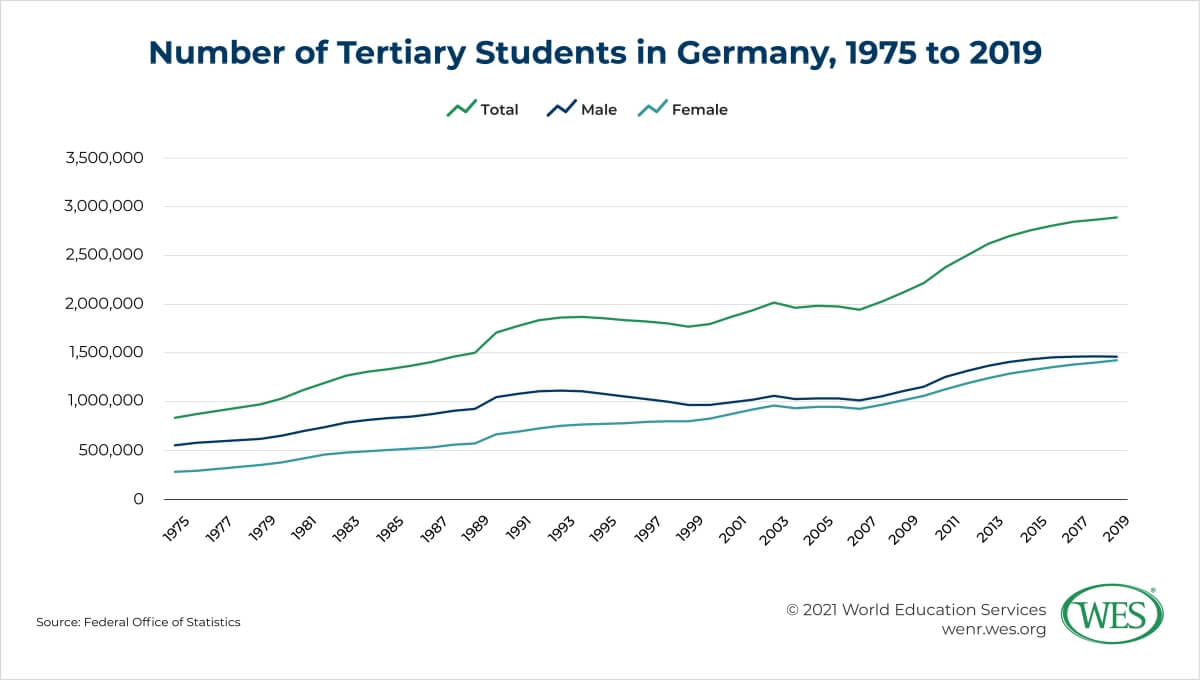

Until the 1960s, university education in Germany was a privilege of small upper-class segments of society; women were not allowed to matriculate at universities at all until the late 19th century. The two World Wars and purges at universities during the regime of the National Socialists (1933 to 1945) were detrimental to the development and expansion of the German higher education system. After World War II, factors like swift economic development, rising incomes, the abolishment of tuition fees, and the introduction of federal financial aid eventually led to a rapid expansion of university education. Between 1947 and 2010, the number of tertiary students jumped from just 80,644 to 2.2 million. Over the past decade, the number of students grew by an additional 32 percent, to 2.9 million in the 2019/20 academic year. It should be noted that these numbers include students from the German Democratic Republic—about 284,000 in 1989—that were incorporated after reunification, as well as the growing number of international students.

Despite this marked increase in enrollments, however, tertiary education participation rates in Germany are extraordinarily low for an industrialized country. Only 33 percent of the country’s 25- to 34-year-olds had attained tertiary education qualifications in 2019, compared with 49 percent in the Netherlands, 50 percent in the U.S., 52 percent in the U.K., and 70 percent in South Korea.

This low ratio is attributable, at least in part, to Germany’s long-standing separation between academic and vocational education, with the latter absorbing many students who in other countries might pursue tertiary education. Structural differences in labor market access in certain fields also play a role: Graduates from secondary-level German vocational programs—such as nursing, for instance—can legally work as entry-level professionals. In other countries, employment in these fields typically requires a tertiary degree.

Finally, it should be noted that participation in tertiary education in Germany remains socially imbalanced in general, despite it being offered free of charge at public institutions and universities having reserved admissions quotas for students from low-income households. Consider that households with at least one parent holding a tertiary degree made up only 28 percent of the German population in 2016, but that children from these households constituted no less than 53 percent of university students. By contrast, only 30 percent of children from households where at least one parent had completed vocational education—53 percent of the population—attended university.

Another related issue in German tertiary education is that some 30 percent of students—particularly those from low-income households—do not complete their programs of study, caused by factors like a lack of academic preparation or motivation, and funding problems. It doesn’t help that classrooms are often overcrowded, leading to a deterioration of teaching quality. The rapid growth of university enrollments has financially overburdened German universities, the overwhelming majority of which are government funded and don’t charge tuition fees.

Changes to this funding structure have been debated for some time. The OECD in 2016 went as far as calling the German model unsustainable, but solutions, especially those focused on tuition-based funding models, have been elusive. The introduction of tuition fees by seven states in the 2000s turned into one of the more controversial topics in recent German higher education politics. Although the so-called Uni-Maut levied by public universities—€500 (US$591) per semester on average—was modest by international standards, intense political opposition quickly led to the abolition of fees in all states by 2014.

Types of Higher Education Institutions (Hochschulen)

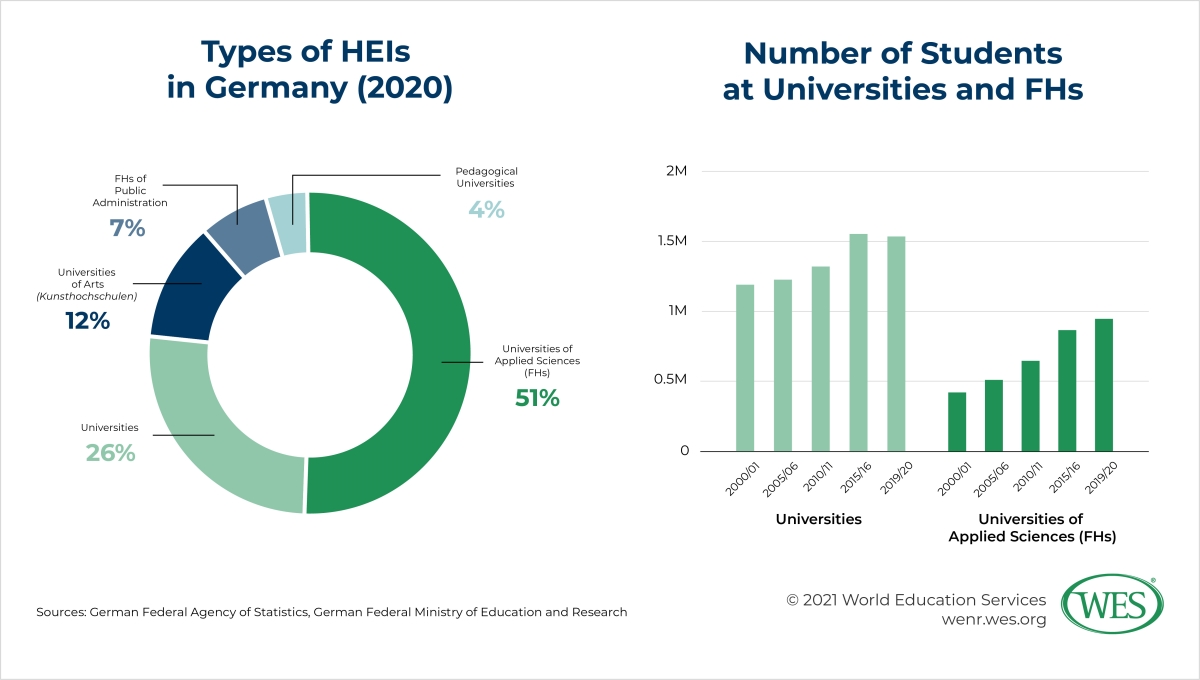

The German higher education system has not only grown over the past decades, it has also diversified. The most important change was the introduction of the Universities of Applied Sciences (Fachhochschulen) alongside the traditional research universities in the late 1960s. In total, there are currently 424 university-level institutions, in addition to a number of HEIs that are not classified as tertiary institutions such as Berufsakademien, sometimes referred to as Universities of Cooperative Education. The latter are more vocationally oriented institutions than Hochschulen.

Universities are mostly large multi-disciplinary institutions that focus on basic research and offer the full range of academic programs, from bachelor degrees to doctorates. However, several universities, especially smaller private institutions, are more narrowly specialized in specific disciplines, such as technical fields, business, or psychology. There were 107 institutions classified as universities in Germany in 2019/2020. In addition, there were 52 universities of arts (Kunsthochschulen) offering programs in artistic fields like music, fine arts, or theater, as well as 6 pedagogical universities, and 16 theological universities that focus on religious education, but may also offer programs in disciplines like philosophy, social work, or nursing.

The university with the largest enrollment is the FernUniversitat Hagen, a public distance education provider with about 75,000 students who learn at various regional study centers across Germany, as well as in Austria, Hungary, and Switzerland. Other large public universities include the University of Cologne with 54,000 students, the University of Munich (49,000 students), and the Technical University of Aachen (45,900 students). Overall, more than 60 percent of German students attend universities.

Universities of Applied Sciences (Fachhochschulen – FHs) are a group of 213 institutions that offer programs in a limited range of subjects, such as engineering, business, or computer science. Their programs are more practically oriented with curricula that focus on applied research and usually include industrial internships. FHs are generally not allowed to award doctoral degrees, although there have been a few exceptions to this limitation in recent years. A further distinction lies in the admission requirements: Whereas the Abitur is required for unqualified access to universities, programs at FHs can be entered with a University of Applied Sciences Maturity Certificate earned in the vocational track (Fachhochschulreife).

A special type of FH are the Verwaltungsfachhochschulen (universities of applied sciences in public administration) which train civil servants for state and federal government. There are 30 of these schools offering education in general administration, as well as specific fields like policing, taxation, or public finance.

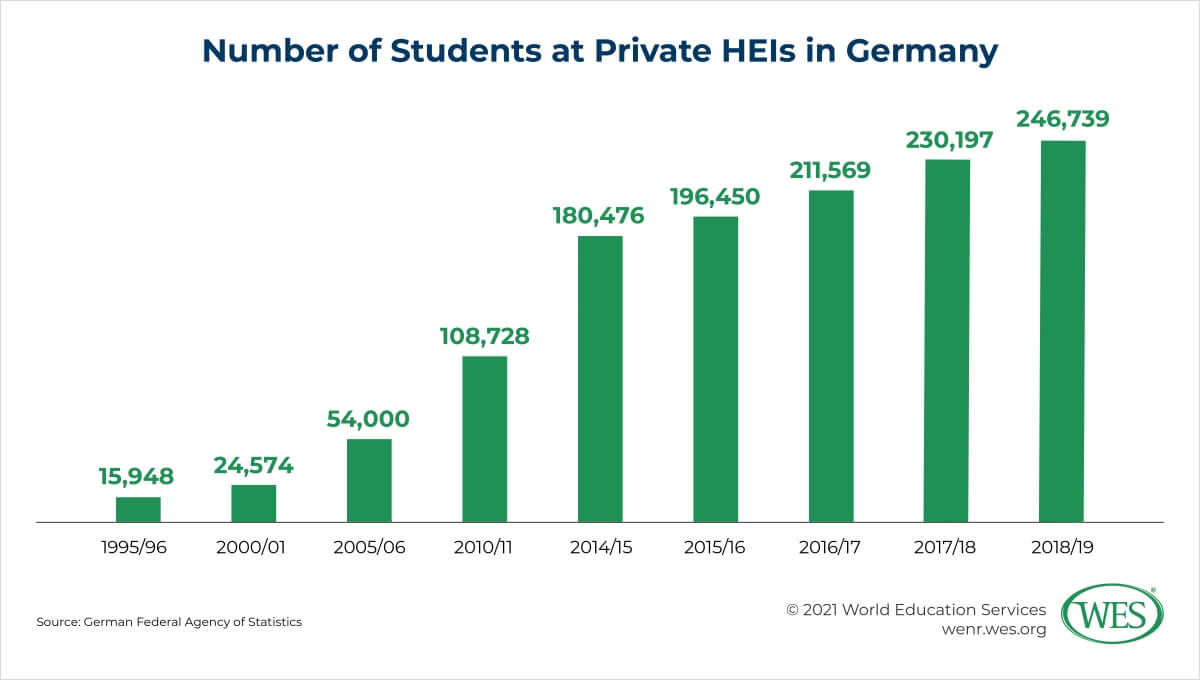

Private higher education in Germany has been growing rapidly in the recent past, but still remains relatively insignificant in a system dominated by public providers. There are presently 117 private HEIs in Germany, including 25 universities and 91 FHs, the vast majority of them founded since the beginning of this century. However, these institutions only enrolled 246,739 students or 8.6 percent of all tertiary students in the 2018/19 academic year.

Private HEIs tend to be smaller institutions focusing on business and technical majors, as well as professional fields like medicine. Many of the theological universities are private as well. Except for some institutions like the FOM University of Applied Sciences, Germany’s largest private HEI with 55,000 students, the vast majority of these private universities enroll less than 2,000 students.

Depending on the institution, it’s sometimes easier to get admitted into private universities than into public ones, but the costs of study are considerable, if lower than in countries like the United States. Private universities charge tuition fees that range between €2,000 (US$2,362) to €20,000 (US$20,362) per year, but may in rare cases be as high as €43,000 for select master programs. Despite these steep costs, private HEIs have nevertheless become an increasingly popular alternative to the more crowded and comparatively underfunded public universities. Students at these institutions tend to complete their studies faster and drop out at lower rates than public university students. Another draw is that many private universities offer flexible part-time programs that appeal to working adults.

Quality Assurance and Accreditation

Germany’s HEIs are recognized and regulated by the ministries of education of the states. To become “state-recognized” and have the same standing as public HEIs, private institutions must also be accredited by the Science Council, an advisory body to the federal and state governments. While Science Council accreditation is voluntary, private institutions without state recognition are not allowed to call themselves Hochschulen nor issue formal academic qualifications. Accreditation is granted for three to ten years based on the evaluation of teaching facilities and staff, quality assurance mechanisms, finances, and the mission statement of institutions.

Quality assurance mechanisms in Germany have undergone significant changes since the introduction of the Bologna reforms at the end of the 20th century. The German states early on implemented a system of program accreditation for the new bachelor and master programs by external non-governmental accreditation agencies—a key concept of the reforms. However, Germany’s federal constitutional court in 2016 ruled it unconstitutional to transfer quality assurance functions to private organizations. Because of this ruling, accreditation is now granted directly by the Accreditation Council, a public institution of the states and the federal government. Under the current system, codified in a 2017 treaty, independent accreditation agencies still evaluate academic institutions and programs, but the Accreditation Council renders the final accreditation decision as an administrative act.

There are 10 accreditation agencies authorized by the Accreditation Council to operate in Germany. Note that agencies from other countries that are registered in the European Quality Assurance Register may be allowed to evaluate institutions and programs in Germany. Two of the agencies authorized by the Accreditation Council are headquartered in Austria and Switzerland.

The accreditation of bachelor and master degree programs is generally mandatory, while other, state-examined programs in professional disciplines are exempted from this requirement. Accreditation is granted for a period of eight years, at the end of which institutions need to apply for re-accreditation. The process is based on the review of self-assessments and on-site inspections by a panel of evaluators that consists of professors and professionals in the field, as well as one student representative, who assess the concept, structure, and curricula of programs.

However, it should be noted that the deadlines for universities to obtain accreditation of their programs vary by state, and that not all programs have been accredited thus far. Program accreditation can be burdensome and expensive for larger universities, so that growing numbers of institutions apply for “system accreditation,” an alternative option that allows HEIs to forgo the external review of each individual program by creating internal, institution-wide quality assurance mechanisms that satisfy the requirements of the accreditation agency. As of 2020, 94 HEIs had obtained system accreditation—a considerable increase compared with the number which had done so in previous years. Another option for institutions is to apply for partial system accreditation, that is, the accreditation of several programs within the same discipline (a process also referred to as “bundled accreditation”). A database of accredited programs and institutions is available on the website of the Accreditation Council.

The Excellence Initiative/Excellence Strategy

In 2005, Germany launched the Excellence Initiative, a well-funded federal project to nurture a group of top-tier, globally competitive research universities. To foster competition between HEIs, institutions were financially incentivized to develop “future concepts” for research, research-oriented graduate schools, and “excellence clusters” (regional research networks). Universities that performed best in these categories were then classified as “universities of excellence” and received special funding.

Critics contended that the project divided German universities into winners and losers and shifted funding priorities disproportionately toward research, thereby harming higher education in the country at large. The OECD noted in 2019 that while Germany is among the top spenders on research and development within the organization, spending per tertiary student is below the OECD average and has stagnated amid increased enrollments.

Despite these criticisms, the German government considered the initiation a success and continues the project with some modifications under the name “Excellence Strategy.” Proponents point to factors like increased research output, an uptick in independent private research funding for top institutions, as well as their growing attractiveness to foreign researchers.

German Universities in International Rankings

Although German HEIs trail universities in countries like the U.S. and the U.K. in international university rankings, they are consistently well-represented in the most common rankings. For instance, seven German universities are among the top 100 in the most recent 2021 Times Higher Education (THE) global ranking (compared with 11 British institutions, seven Dutch institutions and five French institutions). The ranked German institutions are all public universities, a plurality of them universities of excellence. The three institutions rated highest by THE are the University of Munich (ranked 32nd), the Technical University of Munich (41st), and the University of Heidelberg (42nd). The same universities are ranked highest in both the latest QS ranking and Shanghai rankings, which feature three and four German universities among the top 100, respectively. Unsurprisingly, German universities are dominant in subject-specific rankings in fields like mechanical engineering, such as the EU-funded U-Multirank Project.

University Admissions

Admission into public universities in Germany is generally based on the final Abitur grade, which determines how fast students get admitted into their program of choice. Although all Abitur holders are eligible for admission, those with lower grades must often wait longer to enter. The way the system works is that universities consider the number of semesters that have passed since applicants graduated from upper-secondary school with each semester in waiting increasing the chances of admission. In addition to students who meet the minimum grade threshold in a given academic year, a certain number of students are admitted based on waiting periods. The length of these waiting periods varies by field of study. While programs with enough seats admit students instantaneously without delays, applicants in popular fields like medicine or law may have to wait for several years. Additional entrance requirements are relatively uncommon for students with the Abitur, but some programs also require admissions tests or demonstrated foreign language skills.

It should be noted that while the Abitur or a subject-specific maturity certificate are the most common entrance qualifications, applicants with a vocational Meister or Fachwirt qualification are eligible for admission as well. Depending on the state, applicants who completed an upper-secondary vocational program and worked for a few years after graduation may also be admitted, if usually contingent upon special entrance examinations or completion of a probationary period. To boost tertiary enrollments, most German states have eased admissions restrictions in recent years. A record number of 65,000 students without the Abitur were enrolled in universities in 2018.

Admission requirements at private universities are often less strictly tied to the final Abitur grade and may place greater emphasis on entrance exams, interviews and other criteria, although this varies by institution. Universities of Applied Sciences have lower admission requirements than universities and admit students with the Zeugnis der Fachhochschulreife. In a few states, this certificate can also provide access to regular universities.

Admission requirements for international undergraduate students are fairy stringent in Germany. Applicants from non-EU countries who did not complete any post-secondary study in their home countries are often required to complete a one-year preparatory program (Studienkolleg), at the end of which they must pass an equivalency examination (Feststellungsprüfung). Admission into these prep programs requires adequate German language skills and may involve entrance examinations. Even if a prep program is not required, students from all non-German-speaking countries must pass a German language test, such as the Test DaF, unless they seek entry into English-taught programs. The specific admission requirements for 130 countries can be found in a database maintained by the DAAD.

The Tertiary Degree Structure

As in several other European countries, the Bologna Process brought major changes to the German higher education system. Before the reforms, the standard courses of study at German universities were long single-tier programs with a nominal duration of 9 or 10 semesters, although it often took students much longer to graduate. These integrated programs led to the qualification of Diplom—awarded in the sciences, engineering, business, and some social science fields—or the Magister Artium (awarded mostly in the humanities). These credentials could be classified as graduate level qualifications and provided access to doctoral programs. Universities of Applied Sciences, on the other hand, offered shorter four-year programs leading to the Diplom (FH), which usually did not allow for progression to doctoral studies.

After the introduction of the reforms in 1999, almost all Diplom and Magister programs were successively split into undergraduate and graduate cycles and replaced by the new bachelor and master programs. Professional disciplines like medicine or law remain an exception to this structure. Whereas some countries with similar systems—like the Netherlands, for example—switched to the two-cycle structure across the board, Germany maintained long single-tier programs in most professions.

That said, the vast majority of German students are now enrolled in bachelor and master programs, whereas other programs, including state-examined professional programs and non-Bologna compliant programs in artistic fields, make up a comparatively small percentage: In 2018, 49.6 percent of students were enrolled in bachelor programs, 28.3 percent in master programs, 5.6 percent in doctoral programs, and 16.5 percent in other types of programs. Short-cycle tertiary programs below the bachelor’s level are very uncommon in Germany. Less than 1 percent of students enroll in these types of programs compared with an average of 17 percent in other OECD countries.

Credit System and Grading Scale

Before the Bologna reforms, universities did not use credit systems, but quantified course and program requirements in weekly hours per semester (Semesterwochenstunden) with Diplom or Magister programs typically requiring a total of 140 to 170 semester hours on average to graduate. Today, institutions use the European ECTS credit system, which defines one year of full-time study as 60 credit units with one credit representing 25 to 30 hours of study. A three-year bachelor program, thus, requires 180 ECTS credits.

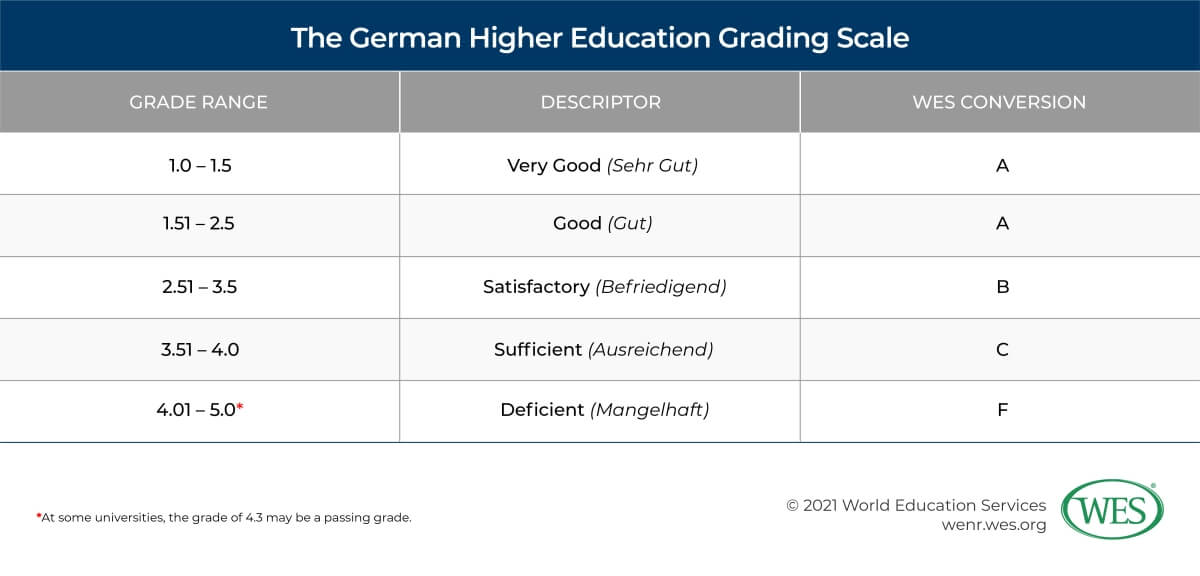

In terms of assessment, German universities continue to use the traditional German grading scale. While HEIs are technically required to use the ECTS grading scale alongside the German scale, it isn’t commonly used. Given that the ECTS scale is a relational or rank-based scale that measures how well students perform in comparison with other students, the absolute German grades cannot be directly converted into ECTS grades. While some institutions list ECTS grades in addition to German grades on their transcripts, the ECTS ranking is mostly limited to final degree examinations, if it is used at all (see the sample document issued by the University of Duisburg Essen linked at the end of this article).

The grading scale is largely consistent across public universities, even if private universities and some programs, such as law programs, use alternative scales. It ranges from 1 to 5 and is different from most numerical grading scales in that the lowest number represents the highest grade. At most institutions, a final grade average of 4.0 is required for graduation, but some universities may graduate students with a final grade of 4.3. Of note, there’s been a trend toward grade inflation in recent years. Between 2000 and 2011 alone, the number of good and very good grades awarded by German universities in final graduation exams increased by 9 percent, although it should be noted that there are significant variations in grade distributions between academic disciplines.

Bachelor’s Degree

Bachelor programs are offered by both universities and FHs and are either three years (180 ECTS credits), three and a half years (210 ECTS), or four years (240 ECTS) in length. The curricula are specialized within the major—there are usually no general education subjects or minor specializations as found in the United States. The programs are divided into subject modules, each comprising several related courses. At the end of the program, students write a thesis, typically worth 6 to 12 ECTS credits. A study abroad period or industry internship may be required, depending on the program. The degree names that have been approved by German authorities are Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Science, Bachelor of Engineering, Bachelor of Laws, Bachelor of Fine Arts, Bachelor of Music, and Bachelor of Education.

Master’s Degree

Master degrees have the same names as bachelor degrees (Master of Arts, Master of Science, Master of Engineering, and so on). The length of the programs can vary between one year (60 ECTS), one and a half years (90 ECTS), and two years (120 ECTS), but it should be noted that a combined credit load of at least 300 ECTS in both cycles is required in the case of consecutive programs in which the master program builds directly on the bachelor program. Admission generally requires a bachelor degree in a related discipline with sufficiently high grades, but students with bachelor degrees in unrelated disciplines may sometimes be able to be admitted via entrance examinations. Some programs may also require work experience for admission. Like bachelor programs, master programs are offered by both universities and FHs. They are modularized and conclude with a thesis typically worth 15 to 30 ECTS.

Doktor/PhD

Doctoral degrees are almost exclusively awarded by universities and research institutes—FHs are only in very rare exceptions allowed to offer these programs. There are two types of doctoral programs in Germany: “individual programs” and “structured programs.” Traditionally, all doctoral programs were pure research programs without coursework, attendance requirements, or hard deadlines. Candidates in these individual programs, which still predominate, independently prepare a dissertation under the supervision of a dissertation advisor (Doktorvater or Doktormutter), usually a full professor or other senior researcher. The degrees awarded upon the defense of the dissertation have different Latin names, such as Doktor Rerum Naturalium (Doctor of Natural Sciences) or Doktor Rerum Politicarum (Doctor of State Sciences).

On the other hand, the Bologna reforms call for structured third cycle programs and have led to the introduction of more “schoolified” doctoral programs in Germany in recent years. These structured programs most commonly require at least one year of compulsory coursework and interim assessments in addition to dissertation research. Most have a set length of three or four years (180 to 240 ECTS) and are taught in English, which means that they are more accessible for international students. Admission requires a master’s degree or equivalent qualification (Diplom, Magister, state exam), although exceptionally qualified candidates who hold a bachelor’s degree may occasionally be admitted as well. Most structured programs lead to the Doctor of Philosophy degree, or PhD (Philosophiae Doktor). While current comprehensive data on these programs are unavailable, it’s clear that they’re growing in popularity in Germany. By some estimates, 23 percent of doctoral candidates were enrolled in structured programs in 2015.

Habilitation