Hotels and History: Affairs at the Ritz Paris | Bonjour Paris

8902 1

Hotels were made for affairs.

And where better to conduct an affair than in the inimitable, iconic surroundings of The Ritz Hotel in Paris?

This was especially true through the febrile, uncertain times of the Second World War when the doors of the Ritz stayed open, the rooms ever luxurious, and the service, if anything, more discreet than ever.

When Paris was occupied by the Germans in 1940, most of the luxury hotels in Paris were requisitioned by the hierarchy of the Nazi party. Hermann Goring, Hitler’s second in command, perhaps unsurprisingly claimed the Imperial Suite of the Ritz Hotel. More surprising, perhaps, was that the whole hotel was not requisitioned for the Nazis but the smaller, less exclusive, rooms near the Rue Cambon entrance and the Ritz bar (made famous by Hemingway and Fitzgerald) remained open to the general public.

One of the residents of the Ritz was Coco Chanel. It was very common for hotel rooms and suites to be rented on a long-term basis. Rich Americans, especially, made these luxury hotels their home in Paris. French writers and artists chose cheaper hotels but both found the convenience of hotels their preferred way of living in Paris.

Coco Chanel’s extravagant suite of rooms in the Ritz was quickly requisitioned. She had already closed her fashion house in the Rue Cambon and initially left Paris for the south, and the comparative safely of Vichy France, but it was a brief escape and she soon returned to Paris. Chanel was offered two smaller rooms on the less palatial Rue Cambon side of the Ritz not facing the Place Vendôme. Chanel had the hotel build a small staircase into the attic from her suite and remained there for the duration of the war. She may have temporarily given up on fashion but her perfume Chanel No 5 was still selling hand over fist in the Rue Cambon– especially to German officers. Chanel was already a very wealthy woman, with many affairs behind her. Her lovers had been rich, often aristocratic, and just as often married, but Chanel was about to embark on an affair in the Ritz Hotel that would not only scandalize but also leave a stain on her reputation for years to come.

Gabrielle Chanel came from the poorest of backgrounds and was born illegitimate (although her parents married after her birth) in 1883 in the poor house in Saumur. She was often on the road with her family; her father, an itinerant trader, finally deserted them so Chanel spent six years in the Aubazine orphanage run by the nuns of the Sacred Heart of Mary. Chanel never fully got over the shame of her upbringing and alternatively denied or changed the details of her birth and youth. Most of the time though she simply refused to talk about it.

Whatever bad memories of her time in the orphanage tainted her life, the nuns taught her to not only to be self-disciplined, but to sew beautifully. Chanel used her talent and imagination initially on decorating hats. She had been the lover of Etienne Balsan, whose family had made a fortune in textiles. For six years he was her protector, and Gabrielle would have been known as a ‘Grande Horizontale’. But Chanel wanted to work, knew the uncertainty of depending on a man, and understood that despite mixing in high society, she could never be fully accepted and had little confidence in their company. Hardly surprising she blurred her background out of all recognition.

It was her next lover (and the love of her life) Arthur Capel who was to set Chanel on her meteoric rise to the best-known couturier, not only in France, but also in most of the world.

Capel was immensely wealthy and incredibly connected to the aristocracy and politicians such as Georges Clemenceau, but he mixed just as easily in the bohemian atmosphere of dancers, artists and writers.

In Paris, Capel guaranteed Chanel’s first boutique on the Rue Cambon. She was an unusual creator– neither sketching nor drawing her designs. Instead Chanel draped her models with fabric and worked from there. Her instincts were infallible; her deceptively simple designs utterly innovative and an immediate success.

When Capel was killed in a car accident in 1919, Chanel was heartbroken. They had been together eight years and although Capel had married the previous year, their affair had continued unabated.

Chanel’s next great affair was with the richest man in England, the Duke of Westminster. The importance of this affair most certainly saved Chanel from the harsh, ignoble consequences that other, less fortunate women suffered at the end of WWII. Through the Duke of Westminster, Chanel was on intimate terms with Winston Churchill and the exiled Duke and Duchess of Windsor. These contacts and the murky secrets Chanel was privy to regarding the Duke of Westminster and Wallis Simpson would stand her in good stead when she was arrested at the end of the war for collaborating with the enemy.

Living in the Ritz Hotel side by side with the German occupiers was obviously going to cast suspicion on even the most innocent of guests. For Chanel who had a German lover also living at The Ritz, she would have no defense.

Hans Von Dinclage had been attached to the German Embassy in Paris since 1936 but it is probable that although Chanel and Dinclage were friends, they only became lovers at the beginning of the war. Spatz, as Chanel called him, was extraordinarily good looking and despite Chanel being in her 60s and Spatz at least a decade younger, their affair lasted throughout the war and after. However sleeping with a German officer was not the only charge Chanel had to face when in September of 1945 armed men from the FFI took Chanel from the Ritz Paris for interrogation. Chanel with Von Dinclage had involved themselves with espionage. Twice Chanel had flown to Berlin in an attempt to open up communications between Churchill and high-ranking Germans who wanted to negotiate a peace between the two countries. However the files on Chanel were far more complex and muddied than a simple attempt to get two parties together. Both she and Dinclage were suspected of spying. Dinclage claimed to be a double agent (his mother was British). Chanel was believed to have worked for the Germans.

The truth may never be known, but for the French, Chanel sleeping with a German was enough to earn her their contempt. Chanel was questioned for three hours before being released to the astonishment of all at The Ritz Paris. Other women had been imprisoned, paraded through the streets with their hair shorn and clothes ripped off during the so called “épuration.” But Chanel had the backing of Churchill and a head full of harmful secrets which saved her from the fate of the pitiless épuration. However even Chanel could not brave it out in Paris and immediately left for Switzerland where she stayed in exile with Spatz. Both her rooms at The Ritz and her atelier on the Rue Cambon stood empty and shuttered.

In 1953, Chanel unerringly judging the mood of France and their desire to move on from the memories of WWII, returned to the Ritz and the Rue Cambon. She was 70 years old and her career was about to start all over again– her affair with Spatz now all but forgotten.

Ernest Hemingway always boasted that he had liberated The Ritz.

The fact that The Ritz was devoid of Germans when he arrived and a small contingent of British soldiers had already established themselves an hour before, did not prevent Hemingway from sticking to his claim. Hemingway was an old Ritz habitué from the 1920s when he was a poor, unknown writer. Now like a returning, conquering hero, he took over a suite in the hotel (and liberated most of the wine cellar). As an accredited war correspondent, Hemingway had broken every regulation in the book including leading an irregular band of militia, carrying a 9mm British machine gun and involving himself and ‘his’ men in skirmishes on the way to Paris.

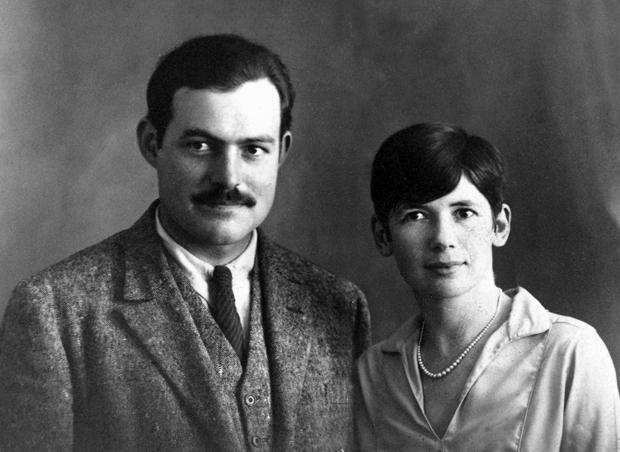

Hemingway was married to Martha Gellhorn, a war correspondent with just as much cojones as he had. And therein lay the problem. Hemingway wanted a woman like his first wife Hadley and his second Pauline who gave up her job at Vogue magazine to look after him. He had left Hadley for Pauline and Pauline for Martha and was now in the Ritz Hotel about to continue his affair with Mary Welsh, another journalist, under the nose of Gellhorn.

Gellhorn was no little admiring wife; she was aware of Hemingway’s exaggerations, embellishments, bravado and little cruelties. But perhaps what Hemingway could not forgive was that Gellhorn had entered the war before him and blagged her way onto Omaha beach on a hospital ship, then tended to the injured in appalling conditions, the only woman amongst 160,000 men. In Paula McLain’s book, Love and Ruin, we learn how Hemingway had deliberately offered his by-line to Gellhorn’s magazine Colliers. They obviously chose Hemingway’s name over Gellhorn, leaving her without press credentials. Gellhorn’s ingenuity, grit, ambition and out-of-date press credentials resulted in her astonishing first-hand account of D Day, while her husband watched the action through binoculars and comparative safety off shore.

Gellhorn was unaware of Hemingway’s affair with Mary Welsh whom he’d met in London and whom he had already lined up as Gellhorn’s replacement and next wife. Hemingway had met Welsh in London in 1944 and was immediately smitten by the curvaceous, diminutive blonde who was working as a feature writer for the Daily Express. Welsh was married to another journalist Noel Monks, but neither spouses, Monks nor Gellhorn, proved an impediment to their future affair. Back in France, Hemingway corresponded with Welsh; he had already decided he was in love with her and Martha was more interested in her career than in him.

On the night Paris was liberated, Hemingway, unaware that Mary Welsh had arrived in Paris and crashed out two floors above him at The Ritz, continued his partying back in his suite accompanied by Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. At 3am, de Beauvois convinced Sartre to go home and, according to Hemingway, continued the ‘partying’ alone with him.

The following day, Hemingway and Welsh were re-united and their affair continued. It is questionable though, that Hemingway’s affair with Welsh was the catalyst for Gellhorn’s request for a divorce. By now, since it was common knowledge that her husband was unfaithful, Gellhorn had started a liaison with Major General James Gavin. (Once more in the Ritz Hotel, Marlene Dietrich decided that she too, quite liked the look of Gavin and spent the night with him.) Gellhorn was not to learn of this betrayal until months later in Berlin where Dietrich once more lured Gavin into her bed and Gellhorn, utterly betrayed, broke off with him completely.

Hemingway and Gellhorn divorced in December of 1945; Mary Welsh had divorced her husband and the two were married in Havana on March 14th, 1946. Their heady days and affair-ridden nights at The Ritz Hotel were finally over.

For Ingrid Bergman, the month of June 1945 and her arrival at the Ritz Hotel would change her well-ordered life forever. She had just won an Oscar for best actress in Gaslight and was beloved worldwide for her role in Casablanca. This was to be a good will tour for the troops. Good for her reputation and good for International Pictures back in Hollywood.

Robert Capa and Irwin Shaw, the novelist, had heard of her arrival and had escaped into the lobby of the Ritz Hotel to avoid the paparazzi and crowds waiting for Bergman outside the hotel. Robert Capa was generally accepted to be the best war photographer in the world. Hard drinking, heavy smoking, an impulsive gambler, he was a close (and competitive) friend of Hemingway. He was a gypsy, following up close at the front of any war he was assigned to cover. His finances were always precarious, his life disordered and unpredictable, and maybe that was why within a short time of meeting the cool, organized, beautiful Swedish movie star, they fell in love and began their affair.

When Irwin and Capa first saw Bergman in the lobby of the Ritz Hotel, they were instantly captivated and sent the infamous letter to her room cheekily inviting her to dinner, part of which read: “We discovered it was possible to pay for the flowers or the dinner. We took a vote and dinner won by a close margin.” The note ended, “We do not sleep.”

Astonishingly Bergman agreed and the three of them went off to Fouquets on the Champs-Élysées where the champagne flowed.

It soon became apparent to Shaw that three was a crowd, and Bergman and Capa’s affair continued throughout the summer months in the Ritz Hotel.

Bergman was taking a massive risk with her career. She was married with a child (her husband, Petter Lindstrom, was her manager) and movie stars, most especially female movie stars, could not afford a whiff of scandal, especially and despite the hypocrisy in Hollywood.

Bergman even had a minder, Joe Steele, employed by International Pictures not only to ensure that Bergman’s stay in Paris went smoothly, but also to make sure her reputation remained stainless.

But Bergman was in love and extended her stay in Paris. She had already been to Berlin to boost the morale of the troops and neither her husband nor the film studio could understand why she was not back in Hollywood.

It was simple; she could not bear to leave Capa.

She finally persuaded him to follow her to America and work as a photographer in the film studios. It was December 1945. The pay was good (and Capa always needed money) but a Hollywood lifestyle in the shadow of a famous married movie star was not what Capa’s life and soul had ever been about. He was a war photographer, a brilliant, brave, war photographer– it was in his blood; it was what he did; it was what he was.

In the summer of 1946, Capa left Hollywood and Ingrid.

Robert Capa, the charismatic Hungarian émigré whose photographs of the human consequences of war still remain as shocking and haunting now as when they were taken, stepped on a land mine in Thai Binh in Vietnam on the May 25th, 1954. He was 40 years old.

In 1949, Bergman fell in love with Roberto Rossellini, the Italian film director. This time she did not escape the scandal and after giving birth to Rossellini’s son in 1950, fled Hollywood and the vitriol of the press and general public.

Bergman died in 1982. Her career had recovered, her accolades renewed but those heady days with Capa in Paris will always remain yet another chapter in the intriguing, on-going life of the fabulous Ritz Hotel Paris.

Lead photo credit : Hotel Ritz Paris