Russian Constructivism – The True Vanguard Art Movement | Widewalls

Russian Constructivism was the last and most influential modern art period to flourish in Russia in the 20th-century. Looking back in 1924, the painter Kazimir Malevich wrote: “We have drawn two conclusions from Cubism, one is Suprematism, the other Constructivism…” Like Suprematism, Russian Constructivism was formed in 1914, before the October Revolution in 1917 and the most important figure, which most associate to stand as its founder, was Vladimir Tatlin. Focused on the careful technical analysis of modern materials, and the refusal of the idea that art should be produced for the art’s sake but as a practice for social purposes, Constructivism borrowed the ideas of the above-mentioned Cubism, but also Futurism and its ideas rooted in the celebration of the modern man and the fast and furious machines. Constructivism art also relied heavily on the criticism and the denial of the spirituality that Suprematism and its leading figure Malevich promoted.

The sometimes violent Constructivist attacks on the idea of the divine, as well as Malevich’s replay and the common goal of the two periods that saw creative production belonging to society at large, form one of the richest documents of the modern 20th-century arts. Let us now take a closer look into one of the most “rational” and sometimes even referred to as a “dark period” in history and reflect upon some of the key ideas of the period, the style of the produced artworks, and its legacy.

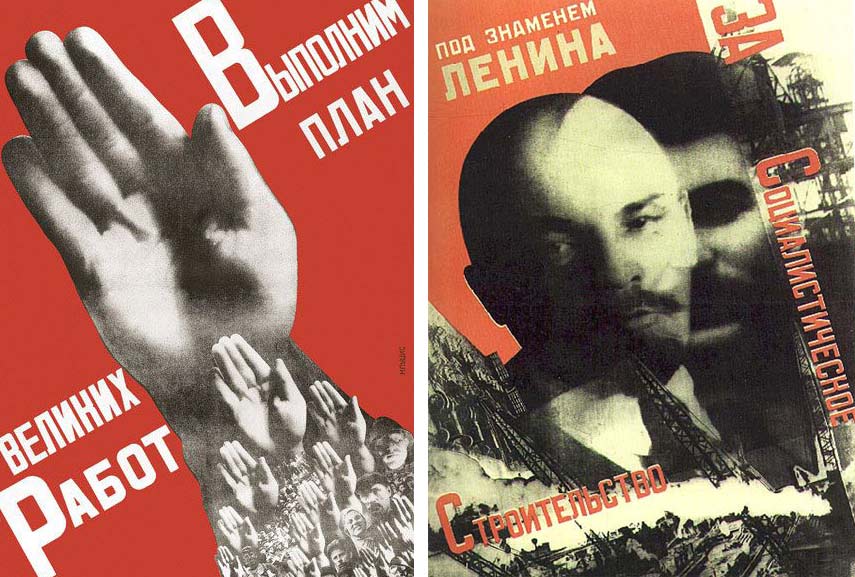

Left: Gustav Klutsis – Workers, Everyone must vote in the Election of Soviets! Image via arthistoryarchive.com / Right: Russian Propaganda Poster.Image via posterwire.com

Mục lục

The Beginnings of the Russian Constructivism

Vladimir Tatlin is often acknowledged as the father of Constructivism. This Ukrainian artist entered the Moscow avant-garde through his traditional training that was pushed, or better to say, supplemented towards a revolutionary way of thinking by a visit to Paris and a meeting with the celebrated Pablo Picasso. In Paris, Tatlin was confronted by the experimentations taking form in Cubism collages, along with the three-dimensional constructions and a series of Picasso’s still lifes made of scrap materials. Tatlin’s admiration for their unconventional modulation, which were composed in such a way that they could have been easily described as ‘constructed’ challenged Tatlin to explore the new approach in his own production. From 1914 to the mid-1920s, Tatlin, along with his Constructivist colleagues created art and design that furiously emphasized materials, volume, revolution, and construction. Embracing the industrial materials, such as wood, glass, and metal, Russian constructivism shifted towards industrial design, and its authors became engineers of the everyday form.

The promotion of rational thought, social and visual interests based on design and proportion rather than sensual appeal attacked the traditional production. The precise technical analysis of modern-day materials by the Constructivist authors was done with the hope that this investigation would eventually generate ideas that could be used in mass production, serving the ends of a modern, Communist society.

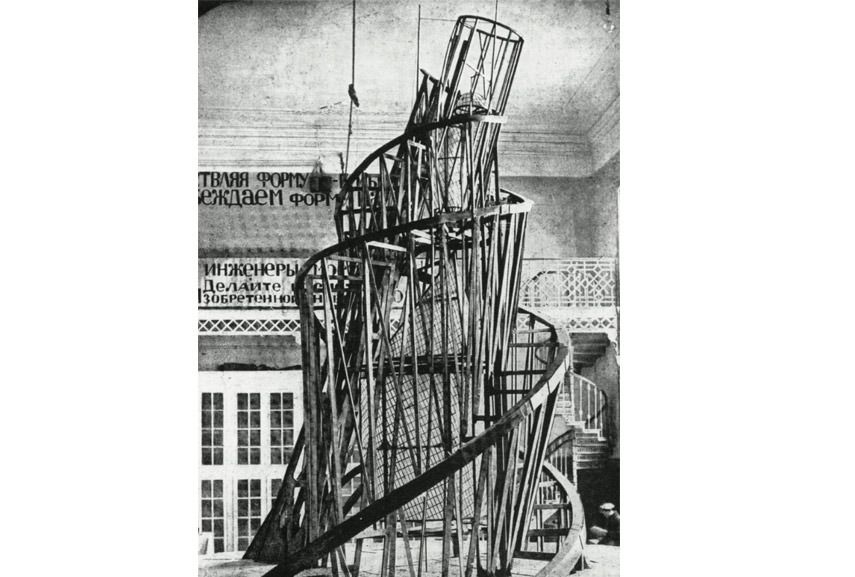

Vladimir Tatlin – Model for the Monument to the Third International.Image via macaulayculkin.tumbrl.com

Constructivism Art and The Revolution

What stood at the root of the period was a desire to express the experience of modern life. Similarly to Italian Futurism, the focus was on the demonstration of dynamism and creativity was seen as a tool for re-invention. Developing after World War I, Russian constructivism pushed towards the production that would serve social change and inspire people to rebuild the society in a Utopian model. The philosophy of using “real materials in real space” the authors used as a tool that was much in line with the Communist principles of the new Russian regime. The art in service of the revolution needed to be bold and stripped off any emotions. This way of thinking different greatly from the standpoint of the Suprematism and the way that the two Avant-garde movements saw art is best described by the following quote taken from the book An Art of Our Own – The Spiritual in Twentieth-Century Art by Roger Lipsey touching upon the testimony of Nikolai Punin implying an underlining solidarity between the two points of view concerning the already mentioned idea of the common goal for the creative production in service of the people.

“[Malevich and Tatlin] shared a peculiar destiny. When it all began, I don’t know, but as far as I remember they were always dividing the world between them: the earth, the heavens, and interplanetary spaces, establishing their own sphere of influence at every point. Usually, Tatlin would assign himself the earth and would try to shove Malevich off into the heavens because of his non-objectivity. Malevich who did not reject the planets, would not surrender the earth since he considered it, justifiably, to be also a planet and could also be non-objective”.

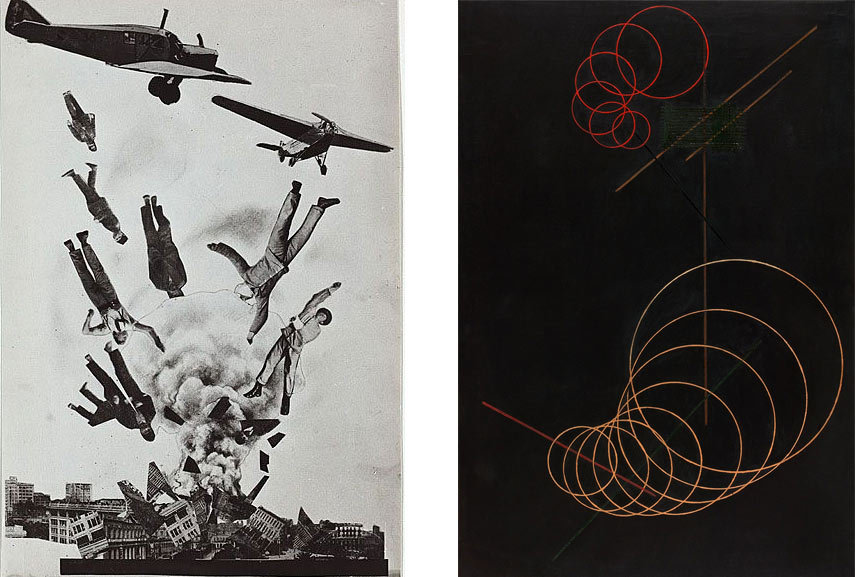

Left: Alexander Rodchenko – Krisis, Photomontage / Right: Alexander Rodchenko – Painting. Images via pinterest.com

Important Constructivist Artists and Artworks

It was not until Tatlin exhibited his model for The Monument for the Third International (1919-1920) that Constructivism was considered truly born. Commonly known as Tatlin’ Tower, the work was never fully realized. Planned to act as a functional conference space and a propaganda center for the Communist Third International, its steel spiral frame was meant to stand at 1,300 feet, making it even taller than the Eiffel Tower. Tatlin focused on using essential materials for modern construction such as glass and steel and the geometrically shaped units embodied the dynamism of modernity. The tower was commissioned and received considerable prominence by the Bolshevik regime, but since it was never built it continues to stand as an emblem of the failed utopian aspirations.

The geometrical non-objective art, the use of the powerful contrast of the black and red color, along with strong typography symbolizes the Constructivism art style that was not only implemented for the production in the traditional modes of high art, but due to the need for mass fabrication artists were influenced to explore the decorative and applied arts. Some of the most important artists of this period were Varvara Stepanova and Ilya Chashnik that dominated in the production of ceramic works featuring abstract planar forms, along with the repeated abstract patterns implemented in textile design work. El Lissitzky and Alexander Rodchenko were influential figures in graphic design, propaganda poster creation, and typography, which made use of bold lettering, stark planes of color and diagonal elements. The tradition of painting was officially declared dead and considered only to stand as design work for future constructions. Yet, Rodchenko produced the only influential series of paintings. His Black on Black series was meant to represent the ultimate end of spirituality and representation and were a direct confrontation to Malevich’s White on White paintings. The black series announced that “Representation is finished; it is time to construct”. Alongside Rodchenko, Aleksandra Ekster, Lyubov Popova, Alexander Vesnin and Varvara Stepanova also declared this art form as dead at the group exhibition 5 x 5 = 25.

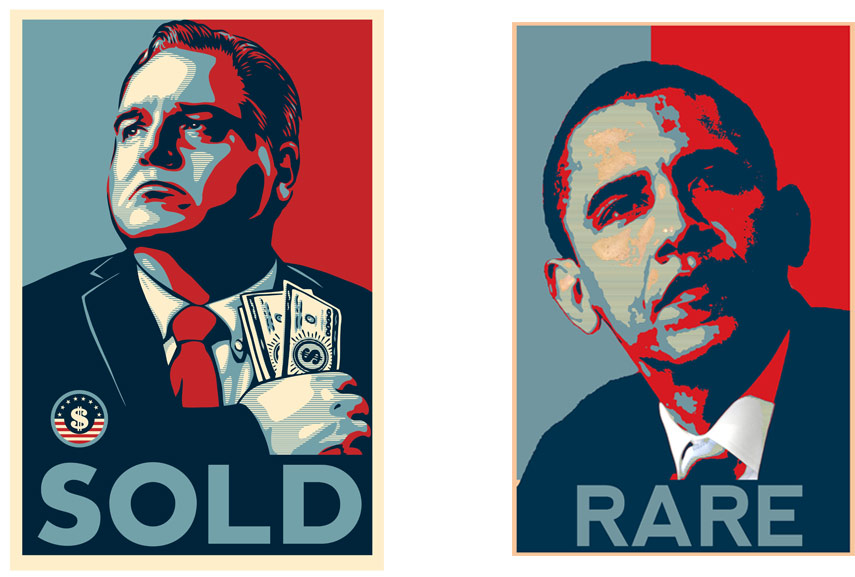

Left: Shepard Fairey – Honest Gil Fulbright SOLD / Right: Shepard Fairey – Barack Obama. Images via wikipedia.org

The Legacy of The Movement

All disciplines of art, including music, film, poetry, especially architecture and theater were touched and transformed during this period that called for complete construction and re-invention of the world, destroying everything before and building the new form from ground zero. As it came to a sudden end in the mid-1920s, due to the growing hostility of the Bolshevik regime to revolutionary art, the ideas and the style of the geometrical non-objective works continued to inspire painters from the West. The International Constructivism flourished in Germany in the 1920s and lasted until the 1950s. A number of Constructivism artist were lecturers at the Bauhaus school, and the design works implemented for the production of propaganda posters, influenced the De Stijl style, along with major graphic and advertising artists today. The ‘Tool of Progress’ manifesto was released by the Dusseldorf Congress of International Productive Artists, with Hans Richteer, Theo van Doesburg of the Dutch movement De Stijl, claiming the constructivism art as a symbol of the modern era. The International movements influenced by the Russian avant-garde movement expended on the idea of art as an object and used new materials to highlight advances in technology and industry.

Editors’ Tip: The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, 1917- 1946

Following World War I, a new artistic-social avant-garde emerged and Europe embraced the need for change. Through close readings of the works of Alexander Rodchenko, El Lissitzky, and László Moholy-Nagy whose careers covered a broad range of artistic practices and political situations, the author Victor Margolin examines the way these three artists negotiated the changing relations between their social ideals and the political realities they confronted. The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, 1917- 1946, offers a great insight into the understanding of the avant-garde period, and the social, political and economic difficulties the artists faced throughout their careers. Beautifully illustrated and covering a range of artistic disciplines if the revolutionary understanding of art is what you adore, then this book is a must-have.

All images used for illustrative purposes only. Featured image: Alexander Rodchenko – Books, 1924. Image via analogue76.com