The Very British History of Burberry

Perhaps no brand is more closely associated with the idea of Britishness than Burberry. Under new Creative Director Daniel Lee, a Yorkshireman and former creative director of Bottega Veneta, the brand’s latest campaign taps into its heritage while advancing images of a modern, multi-ethnic Britain. Shot by Tyrone Lebon, rapper Skepta and footballer Raheem Sterling appear alongside swans waddling on the shore of the Thames, English roses, and plenty of inclement weather—all emblazoned with an Authurian knight bearing the phrase “Prorsum” or “Onward.” It’s very British.

But what being British means these days is an open question. As Burberry looks ahead to its London Fashion Week debut under Lee, textile design professor Sian Weston unpacks the brand’s past in her new book, The Changing Face of Burberry, arguing that Burberry has always updated its vision of Britishness to suit the times–even when it seemed to symbolize the old order.

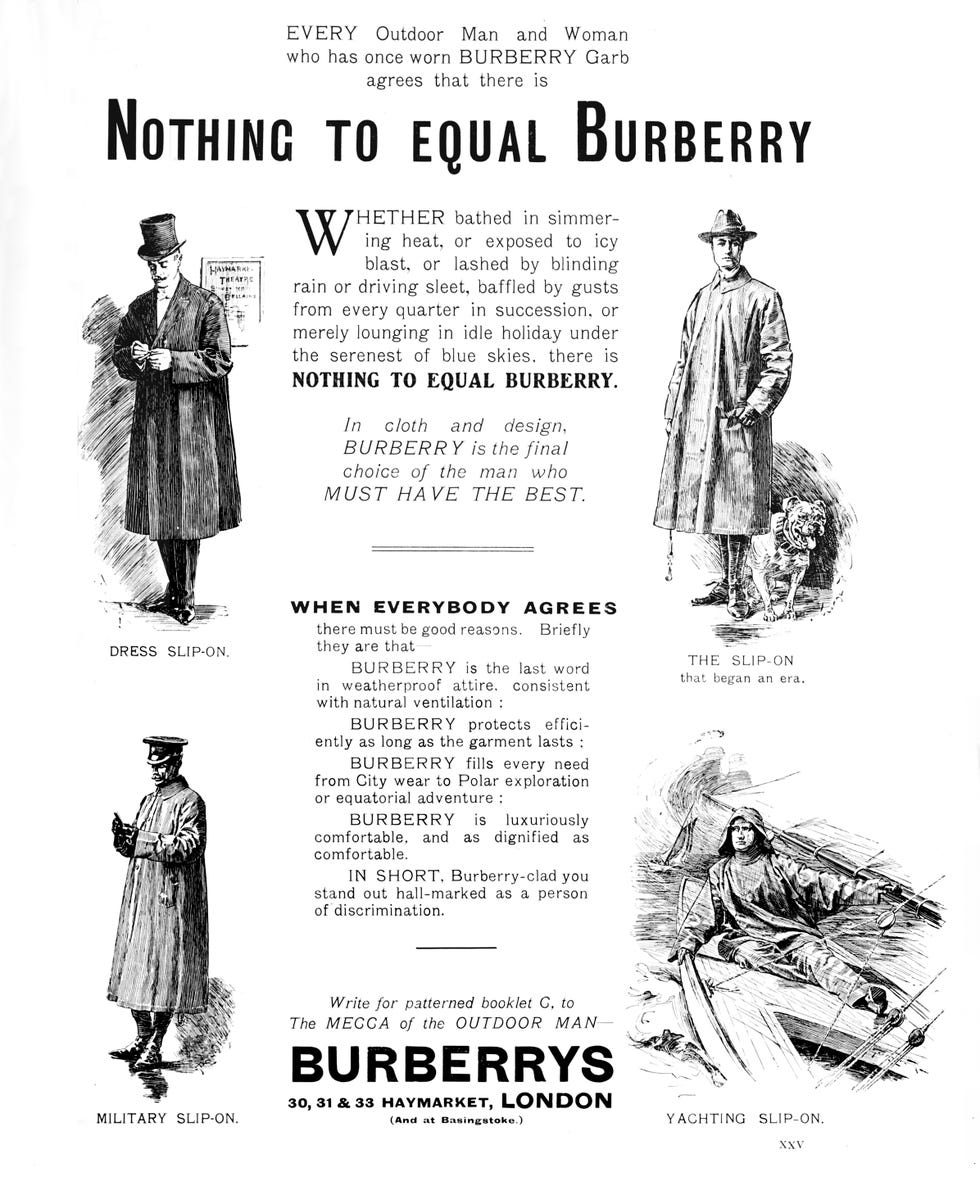

Founded in 1856 by Thomas Burberry, the company began as a manufacturer of technically innovative outdoor apparel. Like the 19th century equivalent of Arc’Teryx, Burberry became the uniform of outdoorsy guys with cash to burn. Thomas Burberry’s sons began using the nova check—a white, black and red plaid against a beige background—to line the brand’s weatherproof garments and let customers know they were buying quality. Advertisements featured explorers, like Captain Scott and Sir Ernest Shakleton, and during the Boer War and World War I, Burberry outfitted officers with their iconic trench coats (most famously worn by Lord Kitchener, a real life British version of Uncle Sam). After the war, the trench entered civilian wardrobes –where it has remained a mainstay of British fashion ever since.

A 1909 Burberry advertisement.

Print Collector

//

Getty Images

“All these endeavors combined a distinct brand of heroic masculinity with nationalism and a heroic sense of Britishness,” said professor Andrew Groves, director of the Winchester Menswear Archive. “It’s unsurprising that Burberry’s earlier years are rooted in the British Empire and a colonial view of the world.”

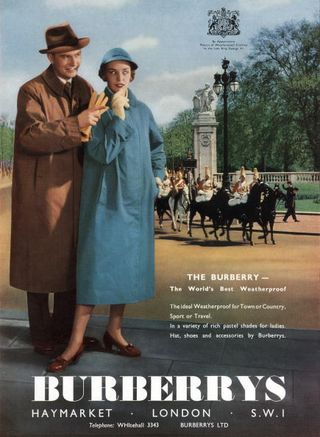

A Burberry advertisement from 1954.

Apic

//

Getty Images

A Burberry runway show in 1980. Very horsey stuff.

WWD

//

Getty Images

But by the end of the 20th century, with class distinctions falling apart, the meaning of Burberry was changing. While the brand was still popular with the Balmoral set, working class musicians like Liam Gallagher were also sporting Burberry in their music videos and making the brand part of the “Cool Britannia” look. This dualism was intentional. Under American CEO Marie Bravo, the company hired two iconic, diametrically opposed house models: Stella Tennant, a patrician English rose with a nose ring, and South London party girl Kate Moss.

“Bravo saw those as two forms of Britishness,” said Sian Weston. Tenant represented the old Burberry consumer, Weston explained—but with an edge–while Moss signified a new kind of striver for the 1990s, an era when Prime Minister Tony Blair declared, “We’re all middle class now.”

A Burberry ad campaign starring Kate Moss in the window of a London store in 2005.

J.Tregidgo

//

Getty Images

However, this class slipperiness also posed a problem for Burberry. As the brand’s appeal grew beyond its traditional bourgeois base in the early 2000s, the fake versions of the nova check began appearing on less desirable consumers, detailed in Owen Jones classic subcultural study, . The nova check design became associated with football hooligans and was even banned by some pubs in the UK for its supposed connection to drunken brawlers. But the final blow was a paparazzi shot published in tabloid The Sun of soap star Daniella Westbrook dressed head to toe in Burberry nova check, hoisting her child (also dressed in the check) out of a matching Burberry check stroller. Many commentators suspected she was wearing fakes, though Westbrook maintains the items were genuine.

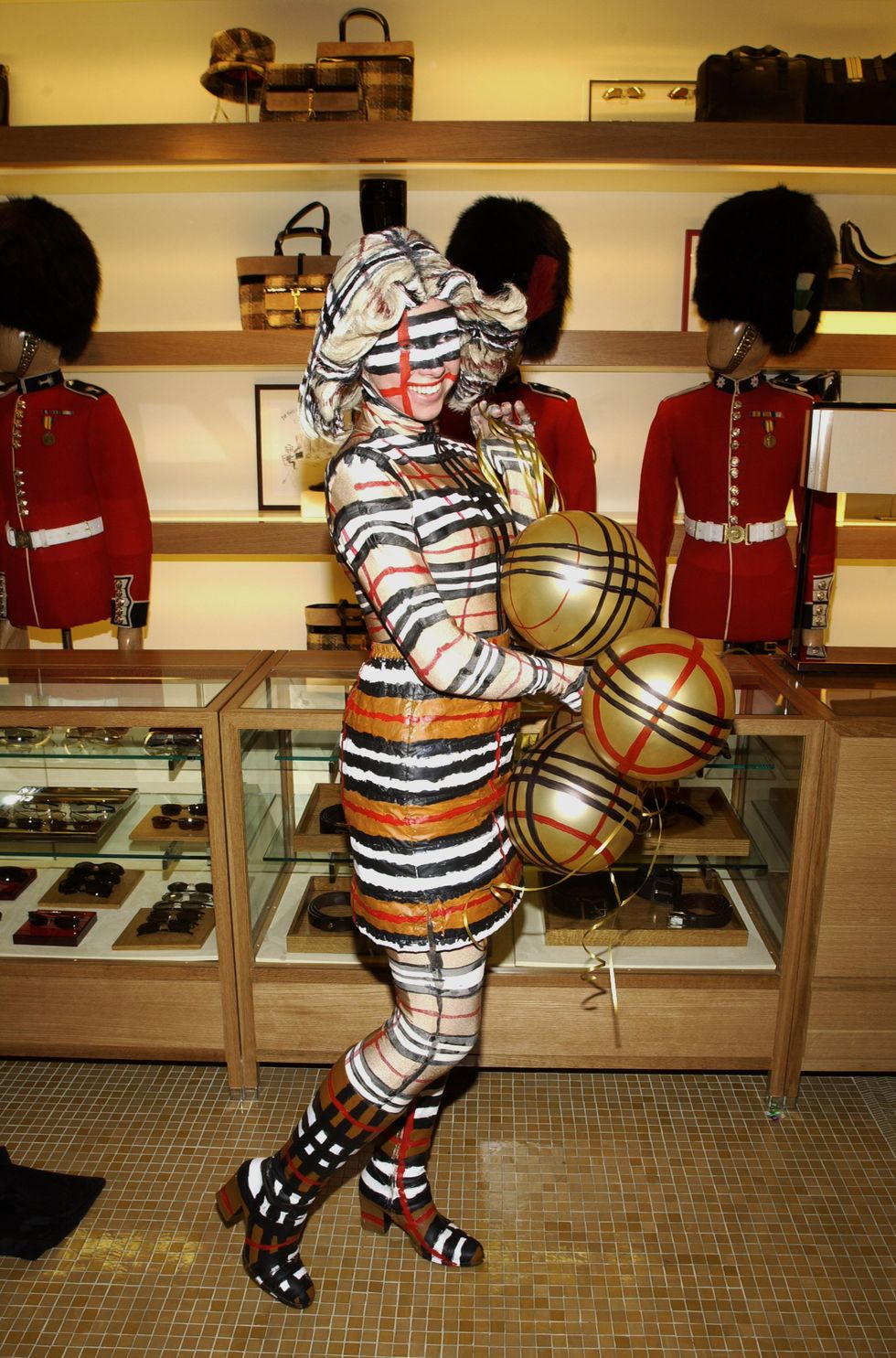

A guest at a Burberry store opening in 2002.

KMazur

//

Getty Images

“It encapsulated everything that was bad about the brand or ‘the wrong people’ buying the brand,” said Weston. Suddenly, the upper crust Burberry symbolized both the excess and tastelessness of “chav” culture, as well as middle class anxiety about poor people spending state benefits on luxury goods they couldn’t afford and didn’t deserve. “There was this moral panic around it,” said Weston, and Burberry was caught in the middle.

Kate Moss and Stella Tennant with then-creative director Christopher Bailey, backstage at Burberry’s Fall 2006 show.

Fairchild Archive

//

Getty Images

With a backlash brewing and a glut of nova check in the market in the early aughts, the brand’s creative director and eventual president, Christopher Bailey, pulled back on the signature design and refocused the brand’s image on its posh heritage. By the 2008 financial crisis, Burberry was well positioned for the era of “Money talks; wealth whispers.” But by 2017, the brand was ready to dabble with the tacky subaltern again, collaborating with the now disgraced Russian designer Gosha Rubchinskiy on his “gopnik” 90s club vision of Burberry.

A look backstage Fall 2007.

Fairchild Archive

//

Getty Images

Now, with Daniel Lee at the helm, Burberry’s new campaign is attempting to do that same two-step it did twenty years ago. Older and middle aged, white customers can identify with images of national treasure Vanessa Redgrave grinning in Trafalgar Square and Liberty Ross leaning against a black Land Rover Defender. But as Bravo did with Stella Tennant, these icons are just a bit twisted–Redgrave looks more like she’s goofing off than preening, and Ross, in a Nova check bikini, has aged into the role of Britain’s hot mom.

At the same time, Burberry is aiming to bring in a younger and more diverse audience with a figure like rapper and record mogul Shygirl–who appeared last year in a music video with FKA Twigs wearing full nova check in homage to Westbrook’s “chavtastic” fit. Gen-Z consumers and millennial designers like Lee likely don’t remember Westbrook at all, and they certainly don’t have the same hangups about fake and all-over nova that their parents did. In the age of all-over logos and luxury streetwear, the tackier the better.

“This new era of Britishness includes everyone,” says Arooj Aftab, a fashion diversity and inclusion consultant who has been closely watching the rollout of Lee’s vision for Burberry. Aftab noted that before Lee’s arrival, when Riccardo Tisci served as creative director from 2017 to 2022, the brand had already made gestures toward a more inclusive vision of Britishness by casting more diverse runway models and dressing footballer and racial justice campaigner Marcus Rashford. But under Lee’s direction, that shift seems to have accelerated. “I feel seen within that,” she said of the new campaign, and she expects other young customers will have similar, positive reactions.

The categories of luxury fashion and streetwear have transformed significantly since the era of chav-bashing, but so has Britain’s position in the world. When Burberry last faced its identity crisis at the turn of millennium, the UK was a cultural and economic powerhouse, but in 2023, it is projected to be the world’s only developed economy to shrink, with Tories stoking culture war issues to distract from economic failings.

Meanwhile, Lee has bet big on a new Burberry for a diverse Britain. While the country may be divided around the monarchy, the Prime Minister, and the economy, perhaps Burberry, that old British standby, is something the United Kingdom can actually unite around.