Vinyl vs. Digital: Which Is Better? – Headphonesty

We attempt to get definitive answers for the long-standing debate on vinyl vs digital.

Is vinyl better than digital? It’s an age-old question that’s been asked (and argued about) time and time again. And one that has never been answered conclusively. Why, you ask? Simply because the answer hinges on subjective things like personal preference, musical taste, and your ear for music.

With the hope of adding a bit more clarity to this discussion, we’ll highlight a few objective factors you can consider when approaching this debate. Let’s get started.

Mục lục

Getting to Know Vinyl

Some of the earliest versions of vinyl first made their appearance alongside the introduction of Emile Berliner’s gramophone in 1888.

The gramophone took inspiration from Thomas Edison’s phonograph and Edouard-Leon Scott’s phonautograph. The former made use of wax-coated phonograph cylinders that could both record and play sound, while the latter recorded sound on paper discs.

But instead of cylinders and paper discs, the gramophone used 5-inch discs made from materials such as zinc or vulcanized rubber. They also needed to be manually cranked to produce sound.

Berliner patented several more records of varying sizes in the succeeding years. There were 7-inch records in 1894, 10-inch records in 1901, and 12-inch shellac records in 1903, which could be played for 3-4 minutes at 78 RPM . These eventually became called the “78s”.

78s were the record format of choice up until the 1950s. Around this time, two new types of records made their debut. In 1948, Columbia Records introduced the 12-inch 33 ⅓ RPM LP (Long Play) record, which offered a combined playtime of 44 minutes for both sides.

RCA Victor (now RCA Records), a close rival of Columbia, also released their own record format – a 7-inch 45 RPM EP (Extended Play) record. This could accommodate 4-6 minutes of music per side and typically used for singles. Both record formats are still in existence today.

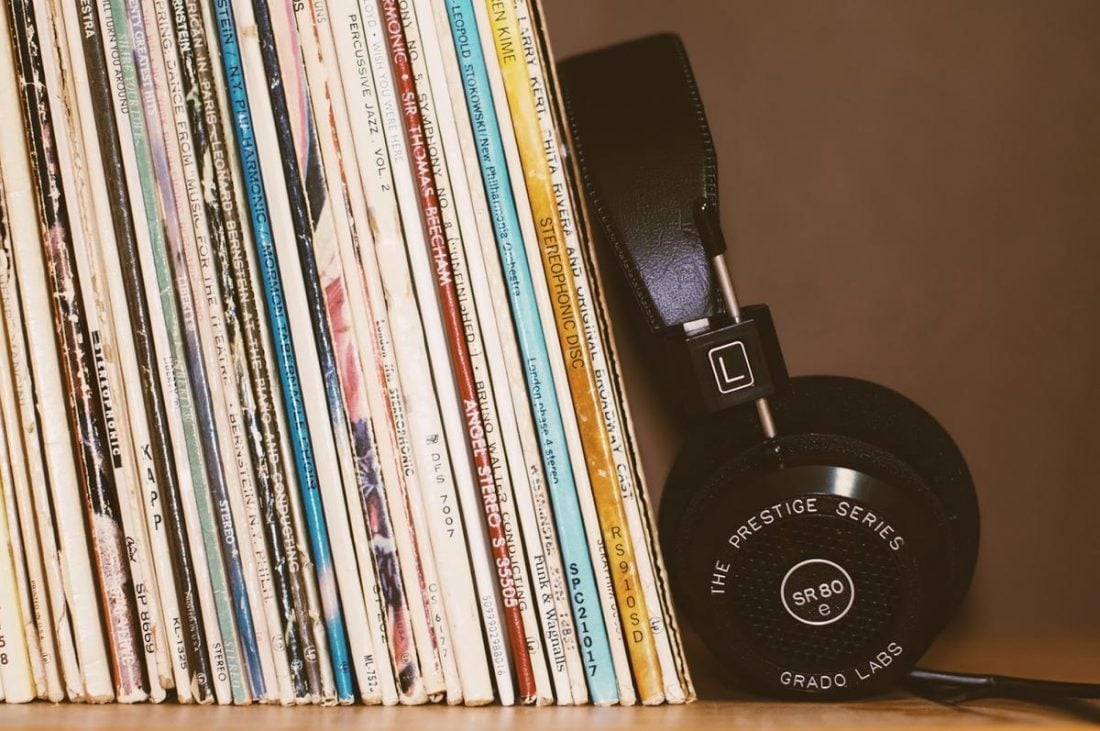

The comeback of vinyl

Vinyl may have slowly receded into the background with the advent of digital recordings in the 70s, but it never truly disappeared. If anything, it became a niche market for music “purists” and collectors.

In the last four years, however, vinyl has gained popularity once more, thanks to renewed interest from millennials.

In Nielsen’s 2017 U.S. Music Year-End Report, vinyl saw an increase in sales (9%) for the 12th consecutive year. That year, over 14.3 million records were sold in the US alone, which was the most number of sales recorded since 1991.

The Recording Industry Association of America’s (RIAA) 2020 Year-End Revenue Statistics Report also noted that vinyl records outsold CDs for the first time since 1986. Vinyl revenues increased by 3.6%, while revenue from CDs nosedived to -47.6%.

How does vinyl work

To understand how vinyl works, it’s important to first understand how they’re made.

- Creating vinyl records begins with the optimization of the digital music files. Sound engineers do this in a studio to ensure the best sound quality possible.

- They feed these digital files through a record or lacquer cutting lathe. Then, a sapphire or ruby-tipped needle cuts the grooves, which represent waveforms, into the disc.

- Next, the newly imprinted master disc gets sprayed with a silver solution and fully submerged in tin chloride. The tin adheres to the silver through a process called electroplating.

- Once removed, manufacturers separate the tin layer from the lacquer disc. This leaves a negative image of the master disc, called a stamper. They do this process twice for both sides of the master disc.

- Then, they take the stampers for record pressing. They do this by placing a “Biscuit”, or a hockey puck-shaped piece of PVC, in the hydraulic press, in-between both stampers. It’s heated to roughly 300 degrees Fahrenheit and compressed together. The stampers leave impressions of the recording on the soft PVC, which later cools down and hardens with water.

After this, it’s off to quality control where each disc will be checked for imperfections — primarily, a visual and audio check.

The disc is placed on a turntable and a diamond-tipped stylus or needle is placed on the outer rim of the disc. As the disc begins rotating, the needle travels through the grooves and picks up the vibrations of the waveforms. The vibrations travel to the cartridge at the end of the tonearm, converting it into electrical signals. These signals are fed into an amplifier and then released through the speakers.

And voilà! Music in your ears.

Getting to Know Digital

Analog recordings imprint a continuous stream of patterns onto a physical surface to create sound — like the grooves on vinyl or magnetic fluctuations on a cassette tape. But in a digital recording, audio signals are converted into a digitized series of binary numbers designed to be read by digital software found in portable music players, computers, and audio equipment.

Today, digital audio can be categorized into two types: CDs and Streaming.

CDs

In the early 70s, several companies invested in the development of digital optical audio recording. However, it was Sony and Philips that eventually came out with the earliest versions of optical CDs. Sony unveiled their prototype at the 1977 Audio Fair, and Philips demonstrated their own version in 1979, alongside a new Compact Disc Audio Player.

In the 80s, Sony and Philips teamed up to produce CDs for commercial consumption. After this, people began to widely consider CDs as a better alternative to vinyl and cassettes because they were:

- Smaller and more lightweight

- More durable to constant wear and tear

- Able to store as much as 80 minutes of data

They also allowed listeners to skip straight to the tracks they wanted to listen to.

How do CDs work?

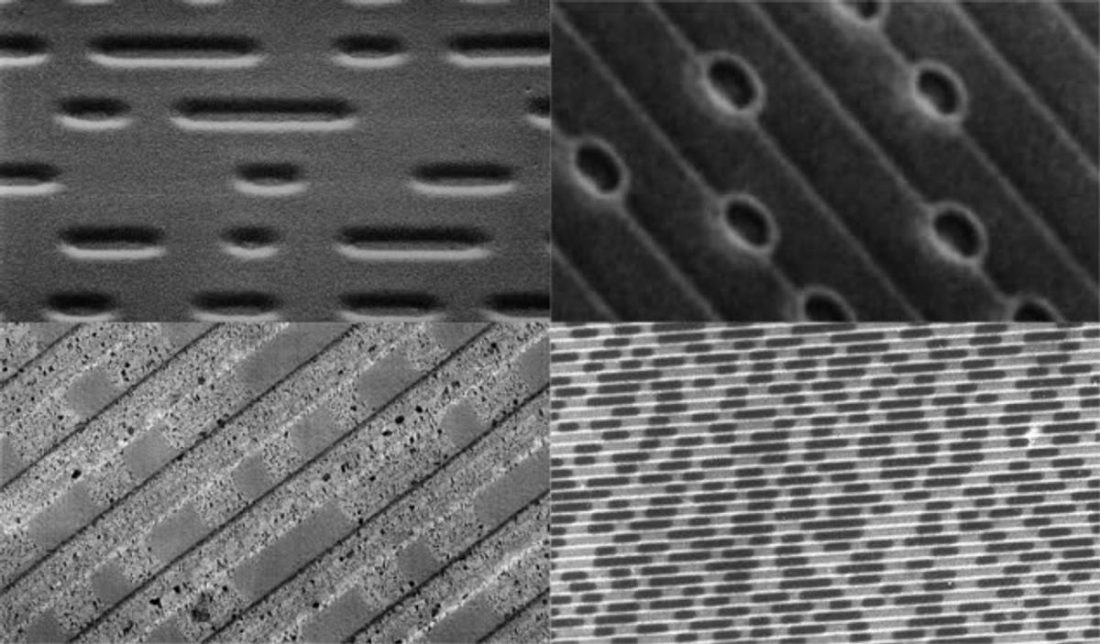

CDs are composed of acrylic plastic (top layer), reflective aluminum (inner layer), and protective polycarbonate plastic (bottom layer).

When creating a digital recording, producers use analog-to-digital converter (ADC) to turn the original analog soundwave into binary numbers stored and read on a CD. This is known as sampling.

Sampling, a.k.a. the method of approximating the path of the original wave by taking snapshots of it at different intervals, is done at the standardized rate of 44.1 kHz, or 44,100 samples per second, making it a pretty good approximation of the original soundwave.

Unlike vinyl and its grooves, there are no actual physical imprints of audio data on the CD itself. Instead, producers ‘burn‘ the audio data as a sequence of “pits” and “lands” into the reflective aluminum layer using a laser beam. Essentially, pits refer to the burned parts, and lands are the unburned parts.

Each time the sequence changes from a pit to a land, that translates to a “1” in binary code. Longer sequences that go unchanged translate to a “0”.

In the same way that vinyl uses a stylus and a cassette uses a tape head to read audio data, a CD uses light to convert the pits and lands into electrical sound signals. As such, no physical contact occurs between the CD and the CD reader, which is also what makes it more durable than vinyl.

Streaming

The concept of streaming and downloading music online can be traced back to 1999 with the birth of Napster.

Napster was a peer-to-peer (P2P) file-sharing network that allowed users to upload and download an unlimited amount of music files for free. It garnered as many as 80 million users at the peak of its popularity. But it also turned the music industry upside down by removing the need to purchase music legally.

While Napster was eventually shut down in 2001 amidst a flurry of lawsuits, it did give rise to other P2P sharing networks such as LimeWire, PirateBay, and BitTorrent. Like Napster, however, these were all short-lived and met a similar demise.

To end the culture of piracy initiated by P2P file-sharing, a new era of music streaming began. This was marked by the entrance of platforms like Pandora, SoundCloud, Spotify, Amazon Music, Qobuz, and Deezer in the 2000s, followed by Apple Music, Tidal, and Youtube Music in the 2010s.

How does Streaming work?

In the older days of P2P sharing, you had to download and store music on discs or computer hard drives. But with today’s music streaming apps, all raw music files exist on a server.

With an internet connection (hopefully a good one), you can now stream tiny data packets containing compressed audio to your device from these servers. A digital-to-analog converter (DAC) on your device then converts these data packets into music. All of this occurs within seconds of you pressing ‘Play’.

In terms of sound quality, there are some excellent options available. Apple Music and Spotify, for example, stream music at 256 and 320kbps at its maximum quality setting, respectively. Spotify, however, is set to introduce a new Hi-Fi streaming option. This will allow the app to deliver CD-quality lossless audio at 1,411 kbps, alongside other apps like Tidal, Deezer, and Qobuz.

Today, Tidal is probably the best option for Hi-Fi streaming. It has an additional tier called Tidal Masters , which offers MQA -encoded (Master Quality Authenticated) audio tracks. This is a technology that allows engineers to convert master recordings into streamable tracks without affecting quality.

Vinyl vs. Digital: Which Sounds Better?

There’s always been a great debate over the sound quality of both mediums. However, while many aspects of music are subjective and entirely dictated by our personal preferences, there are some objective aspects one can consider to get closer to an answer.

Music mastering and production

The way music is mixed for vinyl and digital is fundamentally different, and this affects how it sounds. First of all, the dynamic range of both mediums is significantly different. Vinyl has a dynamic range of 55-70dB, whereas digital music can go up to 90-96dB.

Vinyl’s lower dynamic range means that it has a lower threshold for ‘loudness’ during the recording process. Any sound too loud can cause the turntable needle to jump too erratically. And since vinyl is already fragile enough as it is, particularly loud sounds can cause irreparable damage to the disc. As such, vinyl recordings tend to be ‘quieter’.

On the other hand, with digital music’s higher dynamic range, tracks could be made louder. And perhaps because of that, people in the 90s had the impression that ‘louder’ was better. As such, producers strove to mix louder tracks to make their music stand out from the rest.

Thus, the ‘Loudness War’ of the 90s was born.

(What’s the Story) Morning Glory? is

Oasis’ 1995 albumis often cited as the start of the Loudness War due to its excessively heavy use of dynamic compression throughout the album.

Technically, the practice of pumping up the volume of tracks was already happening in as early as the 40s with 7-inch vinyl singles. It only became widespread in the 90s with the popularization of CDs and digital recording tools that allowed them to push the practice even further.

Dynamic range and compression

So, how did the Loudness War affect music quality in the 90s?

One of the main tools that producers overused to increase track loudness was dynamic compression. This allowed you to turn down the louder parts of a track while amplifying the softer parts. It drastically reduced dynamic range by diminishing the difference between the loudest and softest parts of a track.

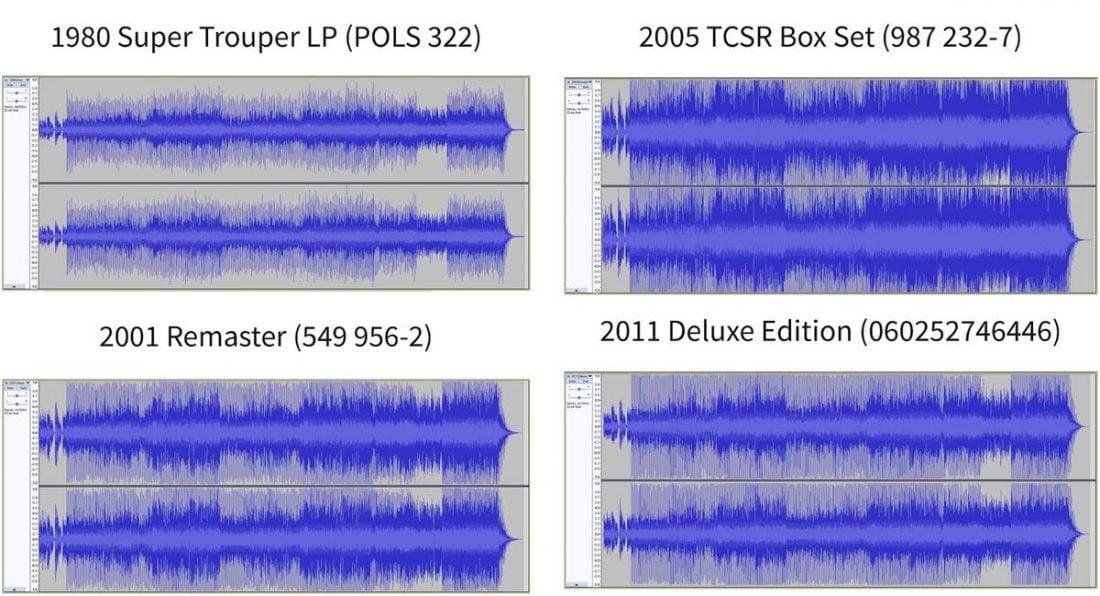

You can see this in the 2005 remastering of Abba’s Super Trouper in the image above. You’ll notice that the original 1980 LP recording has a more ‘spacious’ waveform with well-defined peaks and valleys representing the dynamic range of the track. Whereas in the 2005 track, every layer on the track has been amped up to its upper limits. This narrows down the track’s dynamic range to a point where you’re basically left with a “brick wall” of sound.

In addition to this, when an amplifier goes into overdrive due to increased loudness, digital clipping can also occur in the audio. This further reduces the dynamic range, leaving you with a flat-sounding track with no depth or clarity. And a flat-sounding rack, no matter how loud it is, won’t ever sound great.

The end of loudness

The problem of the Loudness War gained widespread media attention in the late 2000s. At the time, Metallica had released Death Magnetic, which received criticism for the excessive dynamic range compression present throughout the album. The issue was further exacerbated after fans heard a remastered version of the album on Guitar Hero III, minus the compression.

It wasn’t until the late 2010s that the Loudness War truly began to lose traction. Around this time, major streaming services began implementing “audio normalization” in their apps.

This meant that regardless of how loud or soft a track originally was, they would all be automatically adjusted to play at the same volume level. This ultimately rendered “loudness for the sake of loudness” pointless.

Verdict

Winner: Vinyl

Vinyl does indeed have its disadvantages. It doesn’t have long-term durability and it accommodates less data than its digital counterparts.

But because vinyl records remained unscathed by the effects of the Loudness War, you can still expect a better dynamic range that delivers richer, more life-like sound quality than most unremastered digital music released after 1995.

Frequency response

Frequency response is defined as a component’s ability to reproduce a range of frequencies as accurately as possible. Ideally, you’ll want a flat frequency response. This means that, without adjusting any EQ settings, the audio signal remains consistent and unchanged as it passes through a component from the source.

The problem with digital audio is that outside factors, such as the mechanical and electrical properties of speakers and headphones, can affect frequency response. As such, you’ll often see “+/- 6” or “+/- 3” specified alongside the frequency response rate on audio component specs. This represents the amount of deviation you can expect to hear in your audio.

Another issue with digital audio is aliasing. Vinyl players have a frequency response of 20 Hz to 20 kHz, which is essentially the same range of human hearing. A digital sound system, on the other hand, can go as low as 0 Hz but only as high as the specified sampling rate (or Nyquist frequency) will allow.

The Nyquist frequency states that for an audio signal to be accurately reproduced, it must be half the value of the sampling rate.

The problem begins when the Nyquist limit isn’t met. When the frequency exceeds the sampling rate, aliasing occurs which can severely distort audio.

Verdict

Winner: Draw

Since aliasing is a digital error, analog systems are not particularly prone to this. However, the physical components of the player itself limit vinyl, especially when it comes to lower frequency sounds.

On the flip side, the good news is that aliasing in digital audio can be prevented with the help of an anti-aliasing filter. This works by reducing frequencies that go beyond the Nyquist limit, thus preventing them from being sampled and causing distortion.

Common audio problems

Both analog and digital mediums are subject to their own respective audio issues.

Surface noise, rumble, and “wow”

Vinyl is prone to surface noise caused by dust in the LP grooves. This can cause an occasional pop or crackling sound. Similarly, if a slight warp appears on the surface, it can lead to invariable changes to pitch and cause “wow” distortions.

In addition to this, vinyl is also subject to mechanical noise, or rumble. This is a type of noise generated by turntable bearings, particularly when low-frequency sounds are played. Some analog systems struggle with the intensity of lower frequencies, and as such will cause audio distortions like these.

Rumble filters were designed to reduce the sound of bearing noise. However, they also affected the track’s lower bass frequencies thus making them inadvisable.

Quantization noise

Digital audio isn’t susceptible to noise issues caused by surface imperfections or mechanical functions. It is, however, susceptible to quantization noise as a result of lossy compression.

People consider ‘hi-res digital audio’ as an accurate reproduction of the original analog signal. Naturally, the more accurate the sound reproduction, the more data is stored, and the larger file becomes. Of course, not everyone can afford massive digital storage. So, for easier storing and streaming, manufacturers now use lossy compression to reduce the overall file size. MP3 and AAC files are notorious for this and there are several problems with that:

- First is the loss of quality. As the original analog signal gets chopped up and sampled in the compression process, all the “non-noticeable” bits of audio data are removed. While we usually can’t perceive this, it still takes away from the original quality of the music.

- Once an audio file has been compressed, you usually can’t restore it to its original quality.

- Audio files can continue to deteriorate in quality due to generation loss, which is the repeated lossy compressing and decompressing of audio files.

Verdict

Winner: Draw

Both mediums have noise issues that are unique to them.

Audio issues on vinyl are often due to physical discrepancies on the disc or the player. These issues can be very apparent. And while some people might think the occasional crackle adds a charming old-world touch to the music, bigger problems won’t be as appealing.

With digital, anything lost during compression isn’t going to be immediately noticeable. However, this can still take away from a satisfying listening experience, especially if you’re using “okay” audio gear.

Vinyl vs. Digital: What Do Audiophiles Say?

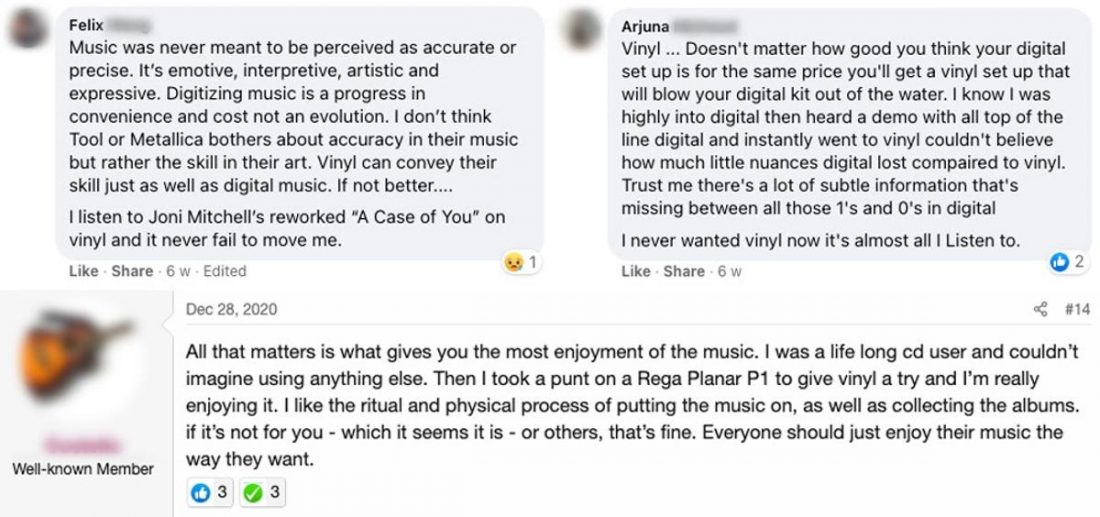

No one can tell you what should sound good to you. Music listening, after all, is a personal journey dictated by your preferences. However, there’s value in seeing how other people, particularly audiophiles, see this debate. Not to change your opinion, but to just get a better sense of the fuller picture.

We trawled through some popular music forums to get a consensus on the topic, and here’s what some had to say:

For vinyl

Many audiophiles argue that vinyl offers a unique expressive sound quality. There’s an inherent warmth in vinyl recordings that make the music feel more tangible and “alive”. Almost like you’re in the same room as the musicians in the recording.

Some say that vinyl is also better at picking up the subtle nuances that often become lost or muddied in compressed digital recordings.

Beyond sound quality, audiophiles are also of the opinion that vinyl is more about the experience, nostalgia, and the unadulterated enjoyment of music.

For digital

When it comes to digital music, audiophiles believe that it can sound just as good as vinyl if mastered well. Many also prefer the crystal clear quality of hi-res digital music, as opposed to the noise and distortion that can sometimes accompany vinyl recordings.

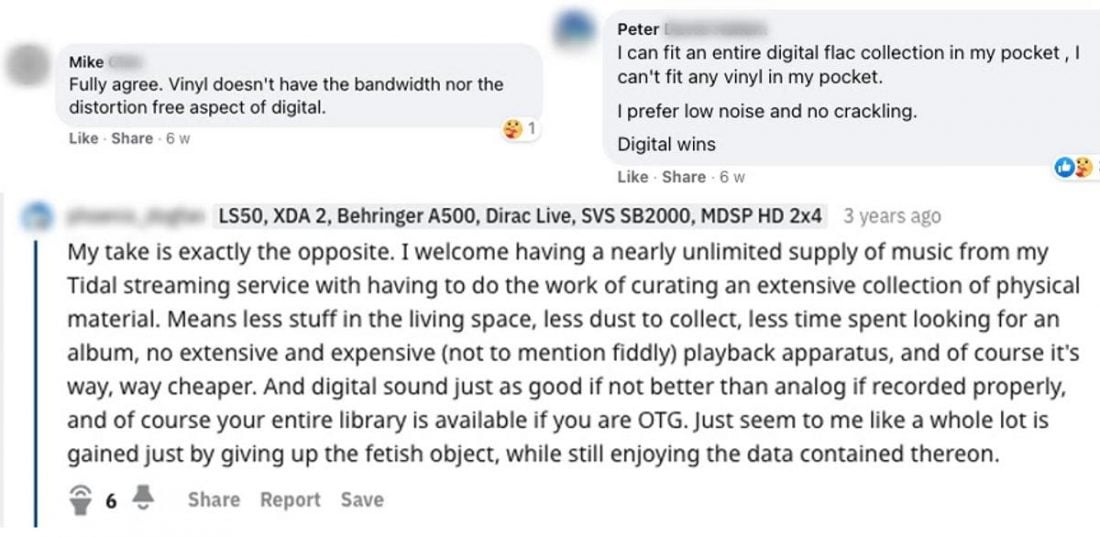

Additionally, beyond sound quality, digital is just an infinitely more convenient and practical medium for storing and listening to music.

The consensus

Those that advocate digital agree on its convenience as a music medium. The format makes it easy to store thousands of albums that you can take wherever you go. It also doesn’t require the enormous upkeep that vinyl does. Meanwhile, vinyl lovers agree that this older medium is more about the experience. It’s about listening to music for the sake of listening to it, and about enjoying the ritual of playing records.

Despite the conflicting opinions, many audiophiles say that both mediums are generally good sources. Neither is completely flawless when it comes to sound quality and at the end of the day, it isn’t just about the format. Some albums will sound good on digital, and others will sound better on vinyl. This also depends on how well an album is recorded and mastered in a studio, as well as how good your equipment is.

Like with all things music-related, it all boils down to your preference and what you enjoy.

Is Buying Vinyl Worth It?

Today, vinyl is certainly more expensive than they ever were. One of the reasons is supply and demand. In the 90s, there was an abundance of vinyl but no demand, since the music world was transitioning to CDs. Today, there’s an increased demand for vinyl, but diminished supply since there are fewer record manufacturing plants left.

Another reason for vinyl’s priciness is manufacturing. The process involves multiple, labor-intensive steps that take time. According to Disc Makers CEO Tony Van Veen, one hour of production yields only about 70-80 records, which isn’t much when you compare it to the digital alternative. And that doesn’t factor in jacket printing and other specialized requests like custom sleeves and colored vinyl. For these reasons, vinyl can be priced anywhere between $25 to $40 per record.

Despite the price issue, vinyl’s popularity is ever increasing. And it’s not just because of sound quality. Here are some reasons why starting a collection can be worth it:

Nostalgia and aesthetics

Vinyl invokes a sense of old-world nostalgia and romanticism that older folk want to revisit, and younger folk want to experience. In terms of aesthetics, there’s something incredibly satisfying about the look of vinyl records, whether they’re on a shelf or in your hands. Oftentimes, the artwork alone makes a record worth buying, and many people feel a great sense of satisfaction having them displayed in their homes.

Tactile experience

For many collectors, the tactile experience that vinyl offers feels more personal. For example, whilst going through your Spotify library, there isn’t really that sense of connection or ownership over the music. It’s words and images on a screen and that’s about it. With vinyl, the music you love is literally in your hands. You can feel its weight, smell the jacket or sleeve, and enjoy the act of setting it up on a record player.

Collection

There’s something very fulfilling about having a physical collection of music that you love. You can at least rest easy knowing that if (for some reason) the digital music world collapses, you’ll always have the music you love the most. Having a record collection is also something like a legacy that you can eventually pass down to your kids.

Increased resell value

Mass-produced CDs tend to depreciate over time. So, a CD you bought for $12 likely won’t even be worth half that amount in a few years. With vinyl, on the other hand, its value increases as time goes on (as evidenced by how much old, used vinyl costs today). As such, people will invest in buying records, not to listen to, but to keep and sell later on for a higher price.

Conclusion

All in all, both vinyl and digital have their pluses and minuses, and none of these necessarily make one medium “better” than the other. At most, you could say that vinyl and digital sound “different” and that both offer listeners a different musical experience.

Some people may prefer the imperfect warmth of vinyl, despite it being a high maintenance medium. Others may prefer the convenience and clarity of digital mediums. Ultimately, it’s up to you, the listener. Hopefully, this article helped give you a more objective perspective on this debate. And if you’re still on the lookout out for a more definitive answer, there’s no better way than to hear the difference for yourself.

How did you find our in-depth look at the difference between vinyl and digital? Which side are you on? If you have some thoughts you’d like to share about the advantages and disadvantages of either medium, don’t hesitate to share them below!