Why America is so polarized with Ezra Klein: podcast and transcript

The title says it all on this one, folks. What is it about the American political system that cultivated this deeply dysfunctional and polarized climate? Last year, we had Ezra Klein on the show to assess how bad things were in the Trump era (conclusion: not great).

Now, Klein is back to discuss his new book “Why We’re Polarized” which provides a systematic look at the deep structural defects in American democracy that are manifesting themselves in two coalitions that are increasingly at each other’s throats.

EZRA KLEIN: There’s this very funny thing the other day, Donald Trump was at, I think it was a prayer breakfast or some religious meeting, and he had a map of his county votes, super red map and he didn’t refer to it or anything. It was like just there for emotional support. There’s this very weird way in which Republicans are able to sit there and look at this map that looks all red despite the fact that it’s fewer people and comfort themselves with that.

CHRIS HAYES: Hello and welcome to “Why Is This Happening” with me, your host, Chris Hayes. Last year, we had an episode with a really dear friend of mine and a colleague and someone that I’ve known since he was 22 when I was 27, Ezra Klein. He might be familiar to you. He’s got a fantastic podcast. He was the founder of the website Vox. He was at the Washington Post before that. And I think the title of that episode a year ago is, I think we called it “How Bad Is It,” which was just the two of us spending an hour wrestling with all of the ways in which these deep structural defects in American democracy are manifesting themselves in the era of Trump in ways that feel like they’re putting this stress on the structure where you can see if you imagine beams that have weight on them, you can start to see it a cartoon, the little cracks showing up in the beam right before the thing splits and cracks.

And the conversation was a lot about polarization, about the asymmetries between the two political coalitions that enabled Donald Trump to be president. And our assessment at the time I think was like, it’s pretty bad. So now, if you’re listening to this on the day this podcast comes out, or even the week that it comes out, we’re in the midst of an impeachment trial in the United States Senate of the president for just the third time in American history. I think the evidence is pretty clear that the president corruptly abused his power to attempt to use official acts for private gain, definition of corruption, the official acts of aid to Ukraine for the private gain of them announcing an investigation into his political rival in order to dirty him up in advance of an anticipated general election, that being Joe Biden.

And I think there’s this prevailing sentiment that I have gotten from people in my life, people that write to me, people online, if you’re in the anti-Trump coalition, the majority anti-Trump coalition, you’re watching this trial happen, there’s a combined feeling of despair and impotent rage about the whole thing. And I think the reason for that is this feeling that the facts are so clear and there’s no persuasion to be had there. We’re going through this trial and they’re making the arguments and they have the evidence and they have these text messages and they have memos and they have testimony and they’ve all this stuff. And the weight of all that seems so clear. And yet, at the end of the day, is any Republican senator going to vote to remove Trump?

Probably not because there is no persuasion because fundamentally this is a power show down between the two coalitions and the two coalitions as represented by different political parties in the United States Senate or representative of something much greater, which are two large coalitions of Americans that are increasingly distant from each other and increasingly polarized and increasingly at each other’s throats.

And there’s a feeling in which the basic structure of American governance is at odds with the status of our polarization, which is there’s all these veto points in American governance. For instance, for removing the president, it’s 67 votes. In fact, it’s never happened. But there’s a million other veto points in American constitutional design. This is what we call checks and balances. It’s what the founders are super proud of, but it means it’s hard to get stuff done. And the whole idea behind the system of checks and balances and lots of veto points is that it forges consensus.

But what if there’s no consensus to be had? And so, what you just get are you can’t actually get stuff done and everyone just hates each other, which is the equilibrium in many ways we’ve ended up at. And so, Ezra Klein has a new book out, it’s called “Why We’re Polarized,” and it’s a fantastic book. I gave a blurb for it, I read an early copy of it. It’s a systematic look at why we are where we are. Why do we have this deep dysfunction embedded in the American political system right now with these two different coalitions that have some really important asymmetries and this perpetual cold civil war between them in which both sides feel aggrieved?

I don’t think both sides are equally aggrieved. Just to be clear on that and we get into that in the conversation, I don’t think, oh, there’s Team A and Team B and they’re all the same. We talk about that as well, but it’s probably the best, most systematic look at why we are where we are as a society and as a political system that I’ve read recently, particularly on this question of polarization, which if you listen to the podcast has been a recurring theme, something we talk about all the time in all different kinds of contexts. I think that Ezra has done this amazing job of uniquely synthesizing a whole ton of political science and history and social science and just insight to lay out almost a systematic diagram of why we are where we are and why we’re so polarized.

The book comes out January 28th, but right now I’m looking at a screen of the impeachment hearings, and it does seem to me like the impeachment trial is the perfect microcosm.

EZRA KLEIN: The book come to life.

CHRIS HAYES: Yes, it is the book come to life and I want to talk about the book. The book is fantastic and rich and really well written and very clear and persuasive and has a great arc of history, trajectory, and social science and then modern political science and political analysis. But before we walk through all that, it seems like the most natural place is just… Having just written a book called “Why We’re Polarized,” what are you seeing when you look at this impeachment trial?

EZRA KLEIN: In some ways, the book itself is an effort to work backwards from what we see in American politics. There’s something here that needs to be explained, and I’ll maybe do this in a slightly different way than I would normally do the book, which is to say that one of the themes that comes into play later in the analysis is simply this, that the American political system is unusual and it is built, among other things, to resist political parties. Of course, then the founders immediately begin a couple of them. And so, when they are constructing the way American politics works, they construct it based on a couple of assumptions.

One of the assumptions is that the core political identity, and identity is going to be important in this conversation, but the core political identity, and James Madison says this explicitly, are state political identities, the thing they are concerned about, the unit of disunity is states. The concern is states will not ratify the constitution or states will, as happens a little bit later in American history of course, secede. And so, the thing that the founders as they build a political system are trying to balance against each other are states, which is why we have, say, the Senate where every state, no matter its size, gets equal representation. And they’re doing that in a context where if some people want more democracy, defined here as allowing white men to vote and some people are more concerned about democracy as a form of mob rule, and then they build this system to balance these things.

And then, what happens over the arc of American history is, of course, political parties form. But particularly over the past 50, 60 years, they’ve polarized. We used to have these very mixed, unusual, uncertain and coherent parties. Now, we have this Republican Party, this Democratic Party, and this system cannot function well given the way it is built in those terms because what it demands, what they thought would make sense for it when they were, again, trying to mountain states, was creating very high levels of needed compromise or consensus to get anything done. And so, you look at something like impeachment where you need to pass a house, then you need a super majority in the Senate, a two-thirds super majority to get this done.

But it is not in one party’s interest to offer that super majority up. It is extremely not in the Republican party’s interest. And so, they won’t. They absolutely won’t. We know how this one is going to turn out as horrible as it actually is. And so, you have to step back and say, what does it mean that we have this system that doesn’t work in the condition that our parties are actually in? What does it mean that we know that foundational structures in our constitutional order cannot be sustained in an era of high polarization?

CHRIS HAYES: Right, so there’s two things that are… The core thrust, or my understanding, the core thesis of the book is this collision course between two things, highly polarized parties that are polarized along both ideological and identity lines, and a presidential system under the U.S. Constitution that is an anathema to systems of high levels of polarization.

EZRA KLEIN: Yeah, and I think it’s worth being specific on what that means. In other countries, polarization is not unusual. It is not rare. There’s actually a really cool paper that just came out a couple of days ago. They created the first, that I know of, historical cross country polarization data set. And what it shows is America’s had the fastest run up in polarization and party polarization of eight or nine peer nations over the past 30 or 40 years. But what is striking is that where we are now in polarization and measured of how much the parties dislike each other is actually not highly aberrant. We’re pretty close to the international average actually.

What was unusual is where we used to be, where we were much, much, much lower than other countries. So that’s a notable thing. Polarization is a natural way that party systems, particularly ones that are structured like ours, will eventually evolve. But as you see, what’s different about our political system, and this is really unappreciated I think, is it is not designed so that if you win power in a polarizing election, in an election where both sides are angry and one side wins and the other loses, then you can actually govern.

To govern, you have to work through divided government, you need to get a super majority in the Senate to overcome the filibuster. You have committees that can veto anything. You have the Supreme court operating with judicial review. The president can be from one party and the head of the Senate from another party and have contrary political incentives. And there’s no way to resolve the disputes they actually have.

And so, other systems that have polarization, polarization can be a real problem. It can be a problem anywhere, but most of the time, it’s not that big of problem because functioning just what you mean is that parties are very different from each other. And so, they present different agendas to the electorate. The electorate votes for one agenda over the other and whoever got voted in on the basis of that agenda can govern.

Now, you look at our system. The presidential candidate who got more votes than the runner up is not the president. The Senate party that got more votes than the runner up Senate party does not control the Senate, the Supreme court, because of that, is controlled by the party that got fewer votes in the relevant elections that would have decided Senate control. And so, you have a system that is not democratic, three of the four major power centers in American politics are controlled by the party that won fewer votes in the key elections. And you have this system where power is split up in a way that it is not in parliamentary systems. And so, it is this system where you need this high level of compromise, high level of agreement, a high level of willingness to see the other party as legitimate and even help them govern, not do things that you can actively do under the rules to sabotage them. You need to let them govern. It is in that system that polarization makes America functionally ungovernable.

CHRIS HAYES: And there’s a famous political scientist who you cite named Juan Linz who wrote this famous paper and then, I think, book called “The Perils of Presidentialism,” which is basically about the fact that these kinds of systems like the U.S. Constitution, these presidential systems in which you have divided legitimacy… So in a parliamentary system, it’s like, oh, the Tories won and the Tory majority will now actually, which is the legislative majority, now actually controls the executive. In fact, the Tories will then appoint ministers who are essentially the cabinet secretary heads. It would be like if in 2018, Nancy Pelosi wins and then Jerry Nadler goes and runs the Justice Department and Adam Schiff runs the CIA.

That’s what it’s like in a parliamentary system. There’s no division between the executive and the legislative in that way. And so, what you get is a majority wins and then they take over the government until there are new elections and they’re kicked out. Here, you’ve got all sorts of different branches that can plausibly claim some legitimacy, who hate each other and want to foil each other.

EZRA KLEIN: Yeah, two striking facts about this. One, America has a long history of invading other countries and then rebuilding their governments and we do not ever, ever give them our government. The reason we don’t give them our government-

CHRIS HAYES: It’s an amazing fact, we literally have people sitting there in Germany after World War II, we have people in Japan and no one’s like, create this system with lots of different veto choke points and claims to legitimacy. We basically never do that.

EZRA KLEIN: Given our adoration of our own constitution, you would think what they would do is control C, copy and paste. Look how great our constitution is. We venerate our founders as demigods, but we don’t do it. And the reason we don’t do it is it is understood that constitutions like ours, systems like ours are actually uniquely unstable. America is the only system with a long history of constitutional continuity that works like ours does. And so, then you get the question of, well, why did it work here? And the answer that Linz gives to why it worked here, and he’s writing this, I think it’s a 1991 paper, is that America uniquely has these very mixed political parties.

You have liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats. The party is very highly regional. So what it means to be a Democrat in the South, and much of the 20th century, has nothing to do really with what it means to be a Democrat in the North. So you have this system where the political parties do not act as ideologically coherent internally consistent units that can work off of a competitive logic. Instead, you have long periods in Congress with the functional governing majority though it looks like it’s Democratic; it’s actually a coalition between Southern Conservative Dixiecrat Democrats and Republicans.

And so, a lot of weird stuff is happening in American politics that makes it for this 20th century period, that is where we baseline our respect for the American political system. That period where it seems to work so well is because it is working differently, but then the party’s polarized. And the thing Linz says, which is the reason these systems break down, and think of something like Mitch McConnell and Merrick Garland is a good example here, is that what you end up having is collisions between two sides that represent different majorities or different forms of democratic legitimacy that have no way of resolving them.

And so, one just, I think, easy way of thinking about this is imagine you get into a situation, just very, very simple to imagine, where Democrats begin routinely winning the presidency. They’ve won six or seven presidential popular votes, although in our system that doesn’t account for as much as you might think, but Republicans have more or less a hammerlock on the Senate because they have a big advantage given the Senate over represents small, rural white states. And so, you can then have a situation where the Supreme Court becomes functionally invalidated because the Republicans will not, under any circumstance, accept a democratic Supreme Court nominee from a democratic president. And then, if the Supreme Court can’t function, you see how this begins to escalate. And in other countries, eventually the military comes in and quote unquote solves a problem.

CHRIS HAYES: Right. And so, this is a great moment to talk about what that 20th-century long piece looked like and why it was actually so bloody underneath that long piece, while it was problematic in its own way. Let’s talk about that right after we take this quick break.

Let’s talk a little bit about what the good old days look like. And I love this. The book opens, I think it opens with people writing in the mid-20th century about how the lack of polarization among American political parties is a problem that no one knows what they’re actually voting for. It’s like choosing between the Elks and the Masons. The Elks are one society you could join, the Masons are another and maybe you like one, maybe like the other, maybe your neighbor’s a Mason, maybe he’s an Elk. But there’s no substantive ideological battle behind that. It’s just like the different clubs that people are in.

EZRA KLEIN: This is super important. One, you have to get rid of the idea that polarization is a dirty word or means something bad or is a synonym for disagreement and extremism and anger and so on, that you can have a very angry, very divided, very bitter system that is not polarized in the sense that the disagreements, as deep as they are, are not structured across two parties, they cross cutting them. And so, a couple of things are happening in that mid-century period. But functionally, America is a four-party political system.

You have Democrats, more or less as we think about them now, think about Hubert Humphrey in Minnesota. You have Dixiecrats, so say Strom Thurmond in the South, who’s a very, very, very conservative Senator, but at that point in his career, a Democrat, you have liberal Northern Republicans and you have then more conservative Republicans. And what’s going on is that when the political scientists are writing that paper at 1950, and this paper gets covered on the front page of the New York Times, which is not normal for political science papers, it actually get some attention, their argument is that the parties and being mixed up in this way, in having a Democrat voting for Humphrey in Minnesota and a Democrat voting for a Strom Thurmond, voting for the same party, which represents these people’s such different ideas about how we should be governed, is actually destroying the citizenry’s ability to clearly and cleanly affect governance because the most important thing we do as citizens tends to be voting for a party.

Politics actually is not just about the individual that you voted for, it’s about the party you put in power. And these parties are not honoring the choices voters are made or even offering them a clear choice. There’s dissent at the time that if you do this in our system, the way our system works, maybe it’ll just collapse into chaos, but people don’t listen or they do listen, but it’s not enough. And so, that said, the thing that you just pointed out that is really important is this depolarized period does have the effect of the parties are able to compromise and work together, but it is built on a bone yard. It is built on Southern Dixiecrats interrupting the ideological clarity of a system.

And so you think, well, why are Dixiecrats Democratic given that they’re very conservative on a lot of issues? And the answer is that the Republican Party is the party that invaded and occupied the American South. And so, the Dixiecrat Party has this hegemony over Southern political representation. There was one period when Democrats had 95 percent of all political offices in the South and they operate in the South as authoritarian one party rule, and there’s fighting within that party. So you have Dixiecrat reformers and relative liberals and conservatives and establishment and all these things.

But what they are doing is, as some political scientist at the time said, the Southern Democratic Party acts as the ruling party in the South and conducts the South’s foreign policy with the rest of America. And the way they conduct that foreign policy is they enter into a governing coalition with the Democratic Party with more or less the deal being that they will support the Democratic Party’s quest for power if the Democratic Party in turn lets them and gives them the power because a huge seniority in Congress and so on. They block anti-lynching laws, they block civil rights laws, they block voting rights laws.

Basically, they want the power to protect racial, white supremacy in the American South. And so, it is true that the parties are not ideologically and, because of that, not that demographically polarized and that creates the conditions for a lot of cooperation. But what is happening is that the reason that’s sustaining is that we are suppressing debate, discussion and action on the central injustice in American life. Oftentimes, the alternative polarization is suppression, not a comedy or even compromise.

CHRIS HAYES: I thought this portion of the book, and I’ve read obviously this is a thing that I spent a lot of time thinking about and talking about the podcast, particularly Reconstruction giving way to the redeemers and the reestablishment of Jim Crow apartheid. But this idea of, it just is a really pungent phrase that really stuck with me of one party authoritarian rule on a racial, white supremacist cast system is what the South is.

After the troops were withdrawn and the reestablishment of Jim Crow and racial apartheid, it’s a one party totalitarian state in some ways. And that one party, and you make this great point in the book, which is that it’s crazy too because it’s one party and they don’t really have competitive elections. All the people they’re saying that Washington accrue insane seniority because you’re never going to lose your seat because you just vote for the Democrat. So then, if you combine that with the seniority system in Congress, all of a sudden, you look around and every party chair is a f—— Southern Democrat.

EZRA KLEIN: And they control everything. The rules committee, judiciary-

CHRIS HAYES: They literally control everything. This cast of the people at the top, the Politburo of the totalitarian Southern white supremacist state ends up ascending to the levels of leadership in the United States Congress, that they are basically running the place. And those names are still etched, they are still the giants. Many of the people that are the people that run that system in the mid-20th century and are blocking civil rights legislation, they’re the people that run the legislative affairs for the entire nation, the people arranging, as you say, the foreign policy with the rest of the country.

EZRA KLEIN: It’s a totally wild period in American politics. And there are a couple of things that make a lot more sense if you think about it in those terms. I know you’ve talked on this show and on the TV show a lot about the filibuster. You know I’m obsessed with the filibuster. But the filibuster is not used very often in mid-20th America even though it’s much stronger. Until 1975, you need a two thirds majority to shut down a filibuster, not just 60 votes. And what is it used for though? It is used to block anti lynching laws. It is used to block civil rights laws. It is functionally, the thing it does is it blocks any progress towards racial equality.

And what is so striking about the way that all progresses is it’s in 1975 that the filibuster is brought down from two thirds to 60. Now, for most of this period, Democrats held the Senate, and yet it is Democrats, in many cases, pushing to bring down the filibuster. And why? They had all this power. What was going wrong? And the answer was that it was a fight with their own Southern wing. It was Democratic Reformers who wanted racial equality, who were tired of Democratic Southerners, Dixiecrats being able to stop it using these rules in Congress.

But there’s all kinds of crazy stuff happening here and it’s one of these things where American politics has very, very unstable and unusual dimensions. There’s just an anecdote I love. I have it in the book that after the 1964 election, Mike Manatos who is President Lyndon Johnson Senate liaison aid, the guy who’s running Senate strategy for Johnson, sends a strategy note to the president, and it’s talking about what will happen to Medicare. And it says that if all of the people who have won and lost are here in DC, president accounted for voting, Medicare will pass 55 to 45.

And at that time, you need 67 votes to break a filibuster. So imagine that political system where they’re war gaming out-passing Medicare and a filibuster isn’t one of the things they’re worried about. It is so different from how things work now that it’s crazy, but the reason that that was happening was the South, which would have given the crucial power to a conservative majority, cared more about retaining good relations with the Democratic Party so the Democratic Party would let it continue doing what it was doing, pushing racial hegemony, pushing white supremacy, than it did on a lot of these other things. It’s a Civil Rights Act that changes all of this. And that’s also this crazy moment. A higher proportion of Republicans in Congress vote for the Civil Rights Act than Democrats, which is a striking thing to me. But it is, nevertheless, Democratic Leaders that bring it forward. It’s Lyndon Johnson as president, and Barry Goldwater then runs as an opponent of the Civil Rights Act, and that is what begins this big realignment of the parties. The Republican Party becomes this fusion of conservatism and white backlash politics. The Democratic Party becomes this fusion of liberalism and a more of a diversifying demographic majority. That creates these conditions for this very heavy polarization, which ends up not affecting just ideology, but which kinds of people in the parties, how split they are demographically. Once you set that flywheel into motion, politics radically changes in a way that the fact that we’ve had parties called Republican, Democratic for so long, I think really obscures how different American politics is in its basic functioning in 2020 than in 1945.

CHRIS HAYES: Yeah, so two things that strike me about this story, and I want to now move to that “What happens post-Civil Rights Act,” because I think that’s clearly the kind of breaking point of the resorting. It’s a reminder of how young the country is in some ways, and also about how long path dependency works. The 1876 election is the one that results in the compromise to remove Northern troops from the states of the Old Confederacy, which they leave in 1877 and then you have a solid South, right? The party of redeemers going all the way basically through 1994 is really the biggest, one of the biggest realignment elections in terms of electing Democrats.

There’s this vestigial impact Democrats — and even after 1964 in the Civil Rights Act, all of those people are still around and the partisan affiliations still continue to endure to the point where Joe Biden, now running for president, was operating in that milieu very much, even though he’s operating obviously post the Civil Rights Act, but it’s still the old system. Even going through the 1980s, where there’s these compromises, everyone’s working out that the people in the body, particularly in the Senate, I think, have learned that the way that this works is you get a few people together and everyone agrees to kind of, as Joe Biden described Bob Dole talking to him about putting one foot in the boat, that everyone makes these grand bargains and then they get it passed. That’s the way politics works.

EZRA KLEIN: It’s a genuine system of compromise. I mean, I think something you really see in Biden is that he believes in a very deep way, that the way the American political system works, and he’s not wrong in important ways on this, is pluralism and that pluralism can be ugly and you get things you want at the cost of accepting things you don’t want, but that’s part of what makes it work. I mean, my disagreement with Biden and a lot of these things, is that I don’t know if he’s not clear or he doesn’t want to admit why the fundamental bargains there are broke down and why they’re not coming back. But the thing he is describing is importantly not wrong. You make this great point, which I just think is super interesting about the way- it’s not like what happens is that the Civil Rights Act passes and the next year the South converts to Republican.

It does begin to go for Barry Goldwater. He wins states in the Old Confederacy for the first time for any Republican, but it’s not like every congressional Democrat or Dixiecrat becomes a Republican. In fact, you have Dixiecrats run for president and you have George Wallace and all kinds of things began happening, but one of the fascinating things there is that politics is not just about material interests and it’s very much not just about ideology. It’s very much about identity. What group am I part of? What groups am I part of? Which political party represents us, which political party likes my group and me and wants to raise us in status and listen to us closely and take what we think about seriously? There’s this period of time as the ideologies of the party scramble, but the identities haven’t changed that much.

A lot of what changes the South is what we might generously call cohort replacement. People aging out of the electorate dying. The younger voters in the South are just conservative and they don’t have quite the same experience with the Democratic Party-

CHRIS HAYES: Right, they have no attachment.

EZRA KLEIN: Republican invasion is not in quite as near living memory. They look around and they begin voting for Republicans and Southern Democrats being converting to the Republican party like Strom Thurmond and a bunch of others. It’s very striking when that happens that, when these Southern Democrats become Republicans, they become the most conservative of the Republicans. They’re not moderate Republicans, they’re not the Republicans from New York. They are the right wing of the Republican Party, and a day before, they had been Democrats.

What you see is a sort of slow change in identity and it’s the identity of being a white Christian voter in the South fusing to Republican political identities that is a large part of what is driving the GOP now. Similarly on the other side, racial and geographic and religious and psychological and cultural identities that are more attuned to diversity and urbanism and cosmopolitanism and so on, fusing into the Democratic identity and that difference between the parties, not just what they believe but who they represent. That is the locus of a lot of our politics right now. Polarization is much more about that than it is about healthcare policy.

CHRIS HAYES: All this stuff is in our life. Rick Perry began his political career as a Democrat. Jeff Sessions, I think Richard Shelby, John Kennedy, who is-

EZRA KLEIN: Jesse Helms.

CHRIS HAYES: Jesse Helms, yeah, but John Kennedy, he was in the Senate now in Louisiana, ran for office as a Democrat. In fact was at, if I’m not mistaken, I think he was at the 2004 Democratic Convention supporting John Kerry. All this stuff is like, this is not distant memory stuff. This transformation has happened over our life. The thing that you just said now, this is the sort of the middle core part of the book and it’s an argument about… So we talked about ideological polarization, but it’s not really ideological polarization. That’s one part of it. We’re sorting on these dimensions of liberal and conservative, but it’s like all these different identities stacked to top each other. So like urban versus rural, cosmopolitan versus traditional, black versus white, religious versus secular, feminist versus patriarchal, I mean on and on and on. They’re all getting stacked up to each other and sorted neatly into these two categories. Talk about what’s happening there.

EZRA KLEIN: The book begins by making this argument that we need to reclaim identity politics and if people are interested, I have a bunch of this part in an audio book excerpt on my podcast, but we have come up with this term in politics for identity, identity politics, and we only aim it at marginalized groups. If African Americans are rallying as part of Black Lives Matter against police brutality in their communities, well that’s identity politics. That’s a particular list of politics from some identity group’s individual experience.

If Donald Trump hates immigration or corporate CEOs want lower tax rates, and for Elizabeth Warren to stop saying mean things about them, that’s just politics, right? That is not true. A lot of the book, as you say, certainly in that first half is building, I hope, a much more rigorous framework for how to think about identity. The essential thing there is we all have many identities and one of this is very easy to activate them when you threaten them. I am Jewish and I’m Californian and I’m the son of an immigrant and I’m a dog owner and I don’t like it when New Yorkers talk down on California, right? You can do a lot to get my backup. At any given time, some of those entities are dormant and some of them conflict with each other.

A key idea here is, you just brought up identity stacking. This idea of crosscutting identities versus what I call stacked identities. If you have crosscutting identities, you have identities that pull you in different directions, so maybe you’re a Democrat in the South, maybe you are an evangelical Christian in an urban area, right? You have identities that one would pull you in one direction politically and another in another direction politically. Something we’ve seen in international evidence is countries that have much more stacked identities are 12 times likelier to have a civil war, the countries with highly crosscutting political identities.

The way American politics worked for a long time was we had a lot of cross cutting political identities. You might be a liberal Republican, a black liberal Republican for that matter. You might be a conservative Southern Democrat who was also a union member and these things kind of all interplayed. As the process of ideological polarization took hold, also behind that, a process of demographic sorting took hold, and so now there is no dense city in America that is Republican. If you are in an urban city, you are very likely to be a Democrat. The single largest religious group in the Democratic Party is people who say they do not have a single religion. They are unaf- they are religiously unaffiliated. The Republican Party is overwhelmingly Christian. Similarly, the Republican Party’s overwhelmingly about 90 percent white. The Democratic Party is about half nonwhite now.

Psychologically there’s been sorting, culturally there’s been sorting, what kinds of TV people watch. I mean it’s gone down to very narrow things, right? Do you live near Whole Foods or Cracker Barrels, right? There’s all kinds of things that can pull this up and when you begin to fuse these identities together, what happens is something that challenges one of them begins to inflame all of them and create these much bigger senses of threat from the other side, which seems more and more different from you.

There’s some great research. You’ve had Michael Tesler on the show and you did a great interview with him. He’s done this research showing that if you look at racialized controversies in the 90s and you polled them, things like the OJ Simpson trial, the Bernard Goetz trial. They’re very controversial, but they didn’t split Democrats and Republicans, they basically have the same views on OJ Simpson. If you polled things like that today, the Zimmerman trial, whether “12 Years A Slave” should win an Oscar, if I remember that one right from memory, 69 percent of Democrats, or 67, said it should, and 12 percent of Republicans said it should. [Editor’s note: We double checked and 53 percent of Democrats and 15 percent of Republicans agreed with “12 Years A Slave” winning best picture.]

I might have that slightly wrong from memory, but that’s basically right. It is not, I cannot stress this enough, it is not that it is newly the case in 2020, that racist, divisive issue in American life. It is layered so closely on top of politics, and similarly when you hear Attorney General William Barr give these speeches about how there is an organized effort by secular left to destroy Christianity in America. That intense layering of Christianity, pretty white Christianity and the Republican party is, that’s a newer thing. It didn’t used to split the parties in this way. These things really escalate conflict and a much higher level of loathing and fear of the other party and much more intense forms of political conflict are not just a predictable result, but in many ways a very rational result to that.

But it’s coming not just because of ideological disagreement. In many ways the ideological stakes of American politics in 2020 seem lower to me than they were in 1965 or 1960. There are much more foundational questions at stake, but the identity stakes of these political conflicts are very, very high. We’re very tuned to feel that in a way we’re not tuned. We have to really work on our higher order cognition to feel a debate over trade policy.

CHRIS HAYES: Right. I mean it’s amazing always, to me, when you take it and you write about this in the book. Just take it out of politics where there’s no substantive ideological content, but if you go into any forum, I’m like, it’s like a TV show forum. People are f—— going nuts at each other as if-

EZRA KLEIN: Yeah, they were sports.

CHRIS HAYES: Yeah. Like they’re arguing about Israel, Palestine, or abortion about whether this show is good and it’s like that- it’s just part of our basic human, I think both the human faculties have, and also the technology that we have access to interacting with each other. That now all that stuff that’s there, we do it in all kinds of places, but we’re doing it now on this most explosive stuff.

EZRA KLEIN: Yeah, I actually want to talk about the technology for a minute because that’s a part of this that I think is super interesting but doesn’t get a ton of attention. 15 years ago or whatever it is, all these smart young programmers create social networks and digital media sites like Buzzfeed and so on. Buzzfeed’s newer than 15 years, but nevertheless, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, all of it. They don’t really know what’s going to work. They don’t really know the ways in which people are going to operate with each other.

Facebook, it’s like, yeah, put some interests on there and you can poke people. It turns out that identity isn’t the slingshot, that what works really well on Facebook, on Twitter, on everything, is things that show your identity, that display a certain identity for you, that draw a boundary of your in-group and the out-group. Some of that can be dunking on people on Twitter. Some of that can be starting a group of memes about how awesome Bernie Sanders is on Facebook. I talked to Jonah Peretti, who’s the founder of Buzzfeed, in the book, and he created Buzzfeed when he was actually at the Huffington Post as a skunkworks for seeing what went viral online. He says that it was really… What they began to find was it was identity and you look at all these early Buzzfeed hits and one of the things they’re showing is that there are more identities than anybody ever thought there was.

32 things only children of immigrants will understand. 15 struggles only left-handers have. 22 things only Eagle Scouts will know. What’s happening is that, as you open up these platforms and people begin just doing stuff on them, when they are algorithmically tuned to reward things, to create the highest level of emotional engagement and conflict and an intense reaction, it turns out that attaching to this social group software we have is a thing that does it. Now we’re all in this hyper group world. It is not, I think, the cause of all this, but it’s certainly an important accelerant of it.

CHRIS HAYES: You know, one thing I just- and you treat this in books, I want to talk about it here is that I always really hate the language of tribalism or group conflict because it’s like, well yeah, I mean the Jews and the Nazis were engaged in group conflict. I guess at a certain level, Nazi was an identity and Jew was an identity. If you talked about the Nazis and the Jews as having a tribal beef or being polarized, you would be missing the story because the story there is a story of oppression, violence and hierarchy.

It’s like this sorting story and the tribal story or the team’s story only gets you so far if you don’t start talking about power analysis, and that power analysis ends up itself being part of the contested fight we have in America about who does have the power, because William Barr and conservative Christians think they’re surrounded and they don’t have the power and children of immigrants who get pulled out of the airport by CBP because they’re Iranian feel like they don’t have the power.

I think one side’s right about that, just to be clear, but you do wrestle with it. I just want to hear you talk through how you take this kind of group tribal framework and then integrate the question of power and hierarchy into it.

EZRA KLEIN: Yeah. I’ll say, I appreciate you saying something that I think the language here is just kind of bad. I try even to stay away from the word tribal in the book. It’s in the stuff I quote from people, but I even really like that word. Calling it group identity conflict is a mouthful.

CHRIS HAYES: Right.

EZRA KLEIN: I’ve not come up with a great answer on this part of it, but what you’re saying is right. What happens when we connect to group identities is that fires up a certain kind of processing that in different contexts can operate in different ways. Sometimes it makes us say something to somebody on Twitter and get mad. Sometimes, by the way, it pushes us towards acts of amazing altruism, right? Somebody in my church needs a kidney and I don’t know them that well, but they’re part of my church and I’m going to help them. So it’s, by the way, not all bad.

A lot of this is how the human structure creates cooperation between people. It’s really about where it is channeled and in what context. The particular thing you’re talking about, I think I may take it in a slightly different direction, which is simply to say this. That one of the markers of this era is a real disagreement about who has holds and is losing power.

CHRIS HAYES: Exactly, yes.

EZRA KLEIN: One of the things for American politics over long periods of time was that there actually was a reasonably stable white Protestant Christian power structure that had a lot of control. Something that drives me mad about the identity politics debate, quote unquote, is that we do not have more identity politics in America today. We have less. What’s happened is that we used to have such a powerful form of identity politics coming from this hegemonic majority that nobody called it identity politics because it was just what it was. It was just politics.

Now that it’s weakened and different groups have the ability to put issues onto the agenda and make claims about how they’ve been mistreated or what they need, all of a sudden we can see that there are identity groups at play here. One of the things I say in the book is that it’s not identity politics when every member of the cabinet forever is a white man. It’s only identity politics when people begin saying that maybe we should have diversity in cabinets and maybe it should be half women and it should reflect America.

The way we have taken a super important way of understanding the world and political conflict and used it as a cudgel against particularly minorities, it just drives me crazy. We are in this period where the difference between a William Barr and a child being put in a cage because his parents came here to ask for asylum. Like that’s a huge difference, and a lot of what is happening in this country is sick and grotesque. At the core of political conflict is a conflict between these two groups that feel themselves winning and losing power in different ways. Functionally what’s happening is that the right, because of its geographic advantages, even as it has a numerical disadvantage, the right has a lot of political power, but it feels itself losing cultural power very quickly.

CHRIS HAYES: Right.

EZRA KLEIN: It feels itself underrepresented on TV. It feels itself underrepresented in academia. It looks at demographics and sees we’re becoming a majority minority nation, a much more secular nation. Above age 65, I think it’s about 7 in 10 Americans are white Christians. Under age 30 it’s 3 in 10. The demographic trends are very fast, unaffiliated, religiously unaffiliated people are the fastest growing religious demographic and are going to pass Protestants in, I think it’s two decades, something like that or three decades. We have a big increase in the share of the country that’s foreign born.

The left fundamentally wants political power and has cultural power and the right wants cultural power and has political power. That’s why you always hear right wingers talking about Andrew Breitbart’s idea that politics is downstream of culture because they think that even if you have the Senate, if you don’t have the culture where the decisions are being made about, how can you speak about gay people and is gay marriage something that should just be part of the American Constitution and identity? Then ultimately you’re going to lose.

This is a particularly unstable equilibrium as we’re in this period of demographic change and everybody… People feel themselves losing power. People feel close enough to gain power. You just look at the change from, we elect Barack Obama, the first African American president with his rising young diverse coalition. Then you get this backlash president and Donald Trump with this much older, whiter minority coalition. You can really see the way power is trading back and forth, and it’s very badly exacerbated by the geographic warping of our political system, such as if the Republican Party had to win a majority of the public in order to win power, which is how things tend to work. It couldn’t act the way it is. It couldn’t have Trump.

What would have happened in 2016 is Donald Trump would have lost by 3 million votes and every Republican would have blamed him for blowing a winnable election and Trumpism would’ve been attacked and ripped to shreds within the Republican Party. Instead, he wins because of the electoral college advantage, so Trumpism becomes dominant in the Republican Party. The way in which the somewhat shrinking white demographic Republican power structure is able to hold on to power and also pass laws and Supreme Court decisions meant to keep power, which is leading to an increasingly small D democratic turn in the Republican Party, I think is a pretty dangerous and distorting part of all this.

CHRIS HAYES: Yeah. You know, I had Mark Galli on the podcast recently who is the editor of Christianity Today who wrote that amazing editorial about Trump being removed from office. We had this long conversation and he’s a real dyed-in-the-wool Christian conservative evangelical. He’s not like some fake Republican who only attacks Donald Trump professionally. He is a true believer. One place I think they are right is that if you are a, say, Southern white Christian gun owner, you are correct that the vast majority of the people involved in producing national American culture in media and Hollywood and scripts and stuff are not coming from where you’re coming from, don’t have your worldview. I think they are correct to see it that way, but the political problem here, right, is we’re careening towards this minority rule problem, right?

You take the structures we have, you take the also geographic stacking that’s happening, which is that people move to cities and they tend to get more liberal, both either through self-selection and also pure effects, is a little murky about how that happens. We’ve got people who are in places like Harris County, outside Houston, which Mitt Romney won by, I think, 100,000 votes and Hillary Clinton won, it was like a 100,000 vote flip from 2012 to 2016. That’s all happening while you’ve got this pathway to minority rule that Trump-McConnellism is carving out, which is genuinely terrifying.

EZRA KLEIN: Yeah, I mean we are hurdling towards a legitimacy crisis and this is again, it’s a place where you can have polarization. The problem is the interaction between polarization and the particular idiosyncrasies and quirks of our system. There’s a study I quote in the book that projects that Republicans should be expected to win 65% of presidential elections in which they narrowly lose the popular vote. 65%. The New York Times had a study that said it is totally possible to imagine the next Democratic nominee winning the popular vote by 5 million and losing the electoral college. That is a bigger difference in the Senate, by the way, than it is at the presidential level. It’s very big at the House level, not just because of geography but also because of gerrymandering, which is another piece of this because when you win power, you can pass rules to help you keep power.

You can gerrymander House districts, you can do things like Citizens United or the decision gutting public sector unions. There’s a lot you can do to create, as you say, a pathway to minority rule in a way that’s very dangerous. The Democratic Party, I think, needs to embrace democracy as a much more fundamental value. One of the weird things is that, as democracy becomes coded as a democratic thing, it begins to look to a lot of Democrats who want to be understood as fair players. Power grabs, you do just things that are right by virtue of that value. I mean, every Democrat will say, “Yeah, sure, statehood for D.C. and Puerto Rico. It’s the right thing to do,” but they won’t touch it because what they actually think will happen and what it will be seen as is, well that’s probably four more Democratic senators.

If you state the logic of this out loud, we are not going to give statehood to D.C. and Puerto Rico despite the fact that you can do that just with a vote in the Senate and the House and a signature. If the residents of those places actually exercised our franchise, it would lead to more Democrats in the Senate. That would be actively illegitimate to do because it would change the balance of power, cheating to give these people a voice.

There’s just a lot of things like that in the system right now, but we’re moving, I’ve seen demographic projections that suggest that we’re going to be in a state in a couple of decades where 30 percent of the Senate represents 70 percent of the population, and 70 percent of the Senate represents 30 percent of the population. I mean, you can really imagine a situation with an increasing divergence between what the public wants and the kind of governance are getting. At some point, people’s willingness to treat that as legitimate and abide by what the Supreme Court that that endless minority rule Senate creates is going to say.

CHRIS HAYES: There’s also like, to me, the other issue here is this. There’s a sort of fundamental battle over who has power and also democracy, right? Where one side has both, I think, ideological strains that are deeply anti-democratic that go back for a while. White supremacy in the South, for instance, was a deeply anti-democratic movement that beating back black enfranchisement, imposing that sort of totalitarian state, one party state. So, there’s a sort of ideological heritage there. There’s also a kind of practical consideration atop that, which is that, “Well, we look at the math and more people that vote then we tend to do worse.” So, we should probably find ways to make less people to vote. So, those two things are sort of on top of each other, I think, on the conservative side. And then on the democratic side, I think you’re right, there’s still not the same full throated commitment as a priority fundamentally to democracy as a kind of organizing principle. But there’s also this fascinating thing to me about the asymmetry between the two parties. And there’s a lot going on there.

To me, the biggest asymmetry is diversity in a deep sense. So, there’s… It’s really wild in Trump’s Washington D.C., the amount of photo ops of just all white men that he does and at a certain point it’s not an accident. Like when he came out after the Qassem Soleimani assassination and it’s just this phalanx of old white men. It looks like a picture from the 1950s, that’s the point, right? That’s exactly what he’s calling when you talk about identity as-

EZRA KLEIN: Yeah, that is a symbolic, I represent you.

CHRIS HAYES: Yes, exactly.

EZRA KLEIN: To a certain, to a certain you.

CHRIS HAYES: But there’s also to me, there’s something deep about… I guess this question of could Democrats nominate their own Donald Trump? Which is a question I’ve been obsessed with since 2016. I would go around in 2016 and say to people, “As you watch this, think to yourself, what would be your breaking point for your own political coalition?” Who’s someone… The person that I came up with at the time, as we play this power game of what would the democratic version be, was actually Kanye West, hilariously.

EZRA KLEIN: You know, somebody else just had this conversation with me and said they’d come up with Kanye West.

CHRIS HAYES: Because it’s like Kanye is charismatic-

EZRA KLEIN: For me, it’s Michael Avenatti.

CHRIS HAYES: Right. Avenatti, exactly. But Kanye’s charismatic and famous already and has this very intense attentional gift of he’s very good at making you pay attention to Kanye West. He’s also absolutely not a person who should ever have the nuclear codes, very clearly. And if you were close to that, you would have to say, I would have to go on television and say, “No. This guy should not have the nuclear codes. No. You cannot. You can’t.” But the reason that I think a Kanye West or a Donald Trump version or a Michael Avenatti who’s another great example, right? Is not possible is because the asymmetry between the two parties in particularly, the diversity represented on the democratic side acts as this sort of internal veto choke points against that kind of version of collective madness, if that makes sense. And I wonder what you think of that theory.

EZRA KLEIN: Yeah, I think that’s right. So, I mean I have this chapter towards the end about party asymmetry, right?

CHRIS HAYES: Yeah.

EZRA KLEIN: Why has the Republican Party become something different than the Democratic Party given that they’re both exposed to a lot of the same forces here? And I make the argument that the Democratic Party has this immune system of diversity and democracy.

CHRIS HAYES: Exactly, yep.

EZRA KLEIN: So, it’s diversity on two levels. One is the one you say right here, which is it sounds symmetrical to say, “Well, Republicans have become a party heavily white and Democrats are heavily non-white party. Republicans a Christian party, Democrats a party of a lot of religions, but those are incredibly different organizational structures.

CHRIS HAYES: Yeah, exactly. Right.

EZRA KLEIN: One allows you to go deep and the other forces you to be very coalitional. This is the long time criticism of the democratic party. Hillary Clinton got this attack a lot as this endless roll call.

CHRIS HAYES: Right.

EZRA KLEIN: You know, this group gets that and that group gets this and so on and so forth. But what it means is that to win the democratic nomination, you need to win liberal white voters in New Hampshire, but also traditionalist African American voters in South Carolina. You need to win the karma-ically curious voters in California, but also Irish Catholics in Boston.

CHRIS HAYES: Right, right. Exactly.

EZRA KLEIN: And so, it selects for a very different kind of politician because you can’t just go super deep in the same way.

The second thing that I do think is really important is that Democrats expose themselves and trust a much broader variety of media than Republicans do.

CHRIS HAYES: Yep.

EZRA KLEIN: So, there’s a new Pew poll that just came out, last week actually, and it shows, it looked at 30 different media outlets and Republicans trusted seven of them. It was Hannity, Limbaugh, Breitbart, Fox News and then it was PBS and BBC and something, I’m forgetting. The Wall Street Journal maybe? And Democrats trusted 20 or 22 of them, something like that. And so, and included center right things on the democratic side, like the Journal. And so, Democrats are very tied to these ecosystems that have mainstream news outlets or academia that push against some of what the Democratic Party wants because the business models in these places and the identities in these places are to not be part of a political movement. So, the fact that also Republicans are much more hermetic in terms of their information.

CHRIS HAYES: Yep.

EZRA KLEIN: I think is also part of why somebody like Trump was able to run up the middle there in a way that it’s a lot harder for somebody to do on the democratic side.

And then finally, and I think this is really important, if Democrats did what Republicans did in 2016, they would lose.

CHRIS HAYES: That’s the other thing. Right. Exactly.

EZRA KLEIN: If Democrats ran a candidate who got 46 percent of the two party vote, that candidate wouldn’t be President.

CHRIS HAYES: Right.

EZRA KLEIN: If they ran Senate candidates who got fewer votes, they wouldn’t be in charge in the Senate, which currently they’re not despite getting more votes. If they had in 2018, split the popular vote, if Democrats had won 50 percent plus one of the popular vote, Kevin McCarthy would be speaker of the House, not Nancy Pelosi.

CHRIS HAYES: Right.

EZRA KLEIN: And so, there’s a very deep thing where the Republican Party is allowed to have a strategy that wins in the minority votes because it wins in a majority of land. And there’s this very funny thing the other day, Donald Trump was at, I think it was a prayer breakfast or some religious meeting…

CHRIS HAYES: Yes, with the map out on the desk.

EZRA KLEIN: And he had just a map of his county votes…

CHRIS HAYES: His county’s. Yeah.

EZRA KLEIN: … Super red map. And he didn’t refer to it or anything.

CHRIS HAYES: It was just out on the table.

EZRA KLEIN: My colleague Erin Lupar said it was just there for emotional support?

CHRIS HAYES: Yes, exactly.

EZRA KLEIN: But there’s this very weird way in which Republicans are able to sit there and look at this map that looks all red despite the fact that it’s fewer people and comfort themselves with that. But so, the Democratic Party actually couldn’t run the same strategy. That isn’t to say the Democratic Party isn’t polarizing, I mean it is totally possible that Bernie Sanders is going to win the nomination and the Democratic Party is going to have a democratic socialist as its nominee. But what is striking to me about Sanders is I don’t think Bernie Sanders could do that. And this is not a criticism of him at all. If he was more identity stack, which is to say, I don’t think, and I’d be very curious what you think of this, I don’t think a female African-American candidate from New York could run as a Democratic Socialist and win in the Democratic Party right now.

CHRIS HAYES: No. No. No. No.

EZRA KLEIN: I think it is partially that Bernie Sanders is a 70-something white guy who is comforting in terms of signaling some cultural traditionalism that also it balances out the ideology.

CHRIS HAYES: You know, I think that’s totally right. And also, a politician who spent his entire career in a state that’s 90 percent white talking to and cultivating ways to talk to, message to and gain the support of white rural voters, which is what Vermont is. And so, I think that he also has, again, it’s like politics is a little like standup comedy, you go to these different rooms and you see what gets a laugh and then you repeat that and Donald Trump of course, is great at that. He sort of tests out new materials, he sees what the base goes for and all politicians do that and Bernie Sanders has been in this milieu that’s just a very white rural milieu particularly for a 2020 Democrat. It was precisely the thing, I think, that hurt him in 2016 where he had a really hard time making inroads among voters of color in the primary. He is… Because I think he’s a quite a good politician because he understands the moderate coalitional politics and I think also has a principled, deep first degree commitment to it. That campaign has worked very hard to make those inroads.

EZRA KLEIN: But that’s also part of the Democratic Party strength, right? It forced him to coalitionally get better with groups that he wasn’t used to, which is not how the Republican Party works right now.

CHRIS HAYES: No, that’s the thing. No, exactly. And this is that deep asymmetry, the fact that you’ve got this sort of self-reinforcing, hermetic, epistemic bubble. You’ve got this straightforward identity that is a sort of core of what the party is and then you’ve got this geographic advantage means that like, right? Trumpism can work in a way that it couldn’t on the democratic side.

EZRA KLEIN: I think just something that’s important to appreciate about polarization and it’s important for appreciating how Donald Trump won because the great mystery of him is how does this totally bizarre, aberrant figure crash into the Republican Party, say that he prefers people who weren’t captured in war, like John McCain. Calls George W. Bush and his father all sorts of names. How does he consolidate the Republican vote? And just one of the dynamics of polarization that you’re seeing play out in impeachment right now, very aggressively, but you see it play out in elections and it’s very dangerous for systems. It creates a real opening for demagogues and dangerous players, is that as the parties become more different, it becomes much more rational to put aside whatever qualms you have with your standard bear, just vote for them anyway.

So, I mean, if Kanye West was running against, I don’t know, Marco Rubio, but Kanye West is going to appoint liberal judges in particular to an open Supreme court seat that would swing the entire Supreme court.

CHRIS HAYES: Yep.

EZRA KLEIN: And Kanye West had Pramila Jayapal as his vice president, not, I’m saying that she would serve particularly in that capacity, but kind of going on down the list here.

CHRIS HAYES: No, absolutely.

EZRA KLEIN: It would become rational to say, “Look, I’m not voting for him. I’m voting so Marco Rubio can’t be president” and that’s what happened. I mean, there was evidence of majority of Donald Trump voters, say they’re voting more against Hillary Clinton then for Trump and this system is not built… That really short circuits modes of accountability when parties do not have the power to choose their standard bears or they say they did in the days of conventions where Donald Trump would have had no chance of becoming the Republican nominee, but once somebody has won the primary, they have to consolidate behind them because it becomes this binary choice. And no matter how bad your person is, the other side is unimaginable.

CHRIS HAYES: Well, I’ve said this before on the podcast and all through 2016 I would be in social settings, I would be at an event or something and people would… The one question, can he win? Can Trump win? Can Trump really win? And I’d be like, “Yes. It’s essentially a 50-50 coin flip.” And the thing that I would also say, and I’ve been saying since then, is if you’re in a room with someone, just pick someone in that room, just pick a person and make that person the nominee of one of the two major parties. And they’re like starting with about 42 percent of the vote.

EZRA KLEIN: I think it might be 44.

CHRIS HAYES: 44. They’re within striking range of being the next President. Literally, a person off the street. Turn to your co-worker and just make them the nominee. And I remember that people sometimes would write about a certain candidate, it would be like a Mondale or it would be a Goldwater and it’s like, “Nah dude, that’s not possible.” New York and California are voting for the democratic nominee whoever it is. And I mean that literally. You cannot get a Goldwater Johnson wipe out. You cannot get a McGovern wipe out. You cannot get a Mondale wipe out. It just doesn’t work that way anymore.

EZRA KLEIN: It’s a key difference in politics now and I think it messes with a lot of people’s thinking and I think by the way, this is a thing that even changes how one might think about the democratic primary, look, I think that there’s probably a two to three point swing between the various front runners there that you could imagine. I don’t even really myself know which way it goes, but if you want to ask who’s more electable between Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, I am open to arguments that one or the other can do 2.5 points better than the other ones can, particularly in key states.

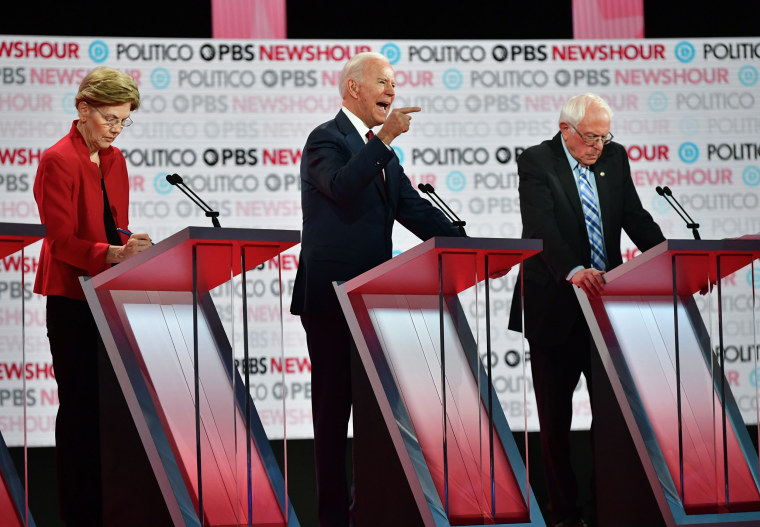

Elizabeth Warren, Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders participate in the sixth Democratic primary debate of the 2020 presidential campaign season co-hosted by PBS NewsHour & Politico at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles on Dec. 19, 2019. .

Frederic J. Brown / AFP – Getty Images

But what is not going to happen, just as it didn’t happen to Trump in 2016, but did happen to people like Goldwater and McGovern, is that they win with 65 percent of the two-party vote or they lose with 40 percent of it. It’s going to be a very narrow band even when the people are very, very different because it’s not just partisanship that is operating. It’s a negative partisanship and the metaphor I use was stacked identities. They’re like a weight holding you in place. The more of them you stack, the harder it is to move around the room in part, because it becomes less rational to move to the other side of the room if you’re just looking at the stakes.

I mean Joe Biden, when he’s talking about segregation to senators and so on, he is a candidate in that period who is somewhat pro-life and has votes in that direction and now he says he will 100 percent protect Roe v. Wade. And what’s remarkable about that moment is that I think it’s a 1976 Republican National platform. It actually says, “Look, there’s some in our party who believe in abortion on demand and some in our party who believe it’s totally wrong and we respect that difference of opinion.” The parties, you can move between parties much more because the parties are much less different if you’re a Democrat looking at Nixon in ’72 and the McGovern election, well, Nelson Rockefeller had liberalized abortion laws in New York.

CHRIS HAYES: Right.

EZRA KLEIN: Bertrand Nixon wanted a universal healthcare and potentially universal basic income. Things were much weirder and that allowed people to imagine the other party actually turning out just fine for them. They sometimes probably voted for the other party in split ticket votes and that just is different now and it just creates, again, I think this is so important for understanding impeachment, that at a certain point the stakes get high enough that the way some of their Republican Party’s has made the calculation is, it just doesn’t matter. Right?

CHRIS HAYES: Right.

EZRA KLEIN: The answer is Donald Trump is our leader and we are on his side not because we love him or think that what he did is even right, although many on the right do love him, but because we are absolutely not going to risk the left getting power in this country. It’s too unimaginable.

CHRIS HAYES: So, let us end on the last chapter problem. I mean you sort of don’t do the solution thing really and I think admirably, but where do you see it going from here?

EZRA KLEIN: Ooh. Where I see it going and solutions are… So, here’s the thing. Polarization for all the reasons we’ve discussed, makes it harder to do anything big.

CHRIS HAYES: Right.

EZRA KLEIN: So, every time if I wander out with solutions, and I do have some in the book, I talk about democratizing things like proportional representation, election-

CHRIS HAYES: Yeah. You have a democracy agenda in the book. Yeah.

EZRA KLEIN: … Filibuster and you get rid of the filibuster and do money in politics stuff. I can give you the Ezra Klein let’s reform the American political system to make governance more responsive and majoritarian governance possible, but for the same… The problem that it is trying to solve is a problem that keeps anything like that from happening.

CHRIS HAYES: Exactly.

EZRA KLEIN: So, that’s bad. Where I see it going is we muddle, I think American politics is going to be bad and disappointing and frustrating and conflict oriented for some time. I think this is going to be a reasonable description of the next 10 to 15 years. Things will change in ways that I cannot predict as demography changes, as the situation changes. If 10 years from now Texas is reliably blue or 15 years from now Texas and Georgia are reliably blue, that changes American politics quite dramatically.

CHRIS HAYES: Yeah.

EZRA KLEIN: Then maybe other things become very possible. But I think of this much more as a description of how the system actually works. I think the way pundits suggest American politics works and imagine the compromise is always just out of reach, if only Barack Obama would have a whiskey with Mitch McConnell. Or if only you know, Donald Trump would something, something, something, it just isn’t true. So one, this is much more description than it is a prescription, but two, I think that what is going to happen is either we are going to get a legitimacy crisis or demographics are going to change the situation such that some of these distortions begin to fade out of the system.

CHRIS HAYES: Yep.

EZRA KLEIN: One of the just ironies of it all right now is as bad as things feel, I always tell people to not confuse their level and their trend in American life. We’ve talked here about what things were like in that so-called golden age of American politics with segregation in the South and the gender discrimination and what it was like to be an LGBT person in this country. We are at a bad trend moment right this second in American politics. It’s grim the direction we’re going in, but level-wise not many times you’d actually prefer to be here.

CHRIS HAYES: Yep.

EZRA KLEIN: There are maybe a couple, but you wouldn’t want to turn the clock back 30 or 40 years. Go look at Bill Clinton’s platform. It looked on immigration like Donald Trump. And so, I think that if things can just navigate out of this, it won’t be great. I mean, back in the second half of the Obama administration, I was on panels all the time and I know you were doing segments on this about the crisis in American democracy and why we can’t get anything done. And so it was bad, but it can be bad without being a total crisis and most periods in American politics have been pretty bad if you wipe away the nostalgia and the profiles, encourage narration that we now impose on them.

CHRIS HAYES: To me, the best case scenario is essentially the California scenario which is back 15 years ago and I know you and I were sort of around during that period of time there was like a mini think tank…

EZRA KLEIN: I mean, I grew up in California in the middle of all this.

CHRIS HAYES: Right. It was a mini think tank industry of the ungovernability of California, how it was just this… The budgets would always be late and they would have shut downs and there was just, essentially you had this like equilibrium where both sides had a kind of veto power over the other and then it just went away because the Democrats, largely through demographic change, the Democrats just kicked the ass of the Republicans and a state that had once been conservative and then 50-50 just became a democratic struggle.

Now, that did not like solve all of California’s problems. In fact, California has many, many, many pressing problems. It also didn’t get rid of conflict. There are moms for housing in Oakland who are getting SWAT teams coming to pull them out of houses they’re occupying because affordable housing is such a crisis and homelessness. So, it’s not like there’s some beautiful panacea world where all problems are solved past it, but it is a governable state where there are the basic mechanisms of democratic accountability are functioning where people vote for things and they have fights about policy and those, you know, and is not the kind of like morass that it was before. And to me, that’s basically the best case scenario for America.

EZRA KLEIN: I think there’s something to that and I would say that even before that period that you’re talking about, that crisis of ungovernability, although I’m in California right now as I talk to you, and I think it’s not doing… There’s some things I’m pretty upset about here.

CHRIS HAYES: Yeah.

EZRA KLEIN: But before that we had a Trumpeth moment. We had Gov. Pete Wilson, we had Prop 187, which was this very harshly anti-immigrant proposition, we had a lot of basically demographic threat, what I call white threat in browning America politics and I mean just what happened here was that the demographics changed rapidly enough that we sort of ran through that period. Interestingly, because I could see this working out different ways, Texas is another version of this. It also has very diverse demographics, but for reasons both of how Texas Republicans have sort of set up the system or rigged the system, depending on how you want to look at it, but also other factors, it’s at least for now, retained quite at red character.

But what I think is sort of interesting about thinking about those demographic paths is number one, they rely on competition actually being able to express itself.

CHRIS HAYES: Yeah.

EZRA KLEIN: They rely on the system not getting so rigged that the changes cannot actually be seen. But number two, it is by no means just a prescription for one party rule. Look, the most popular governors in the country are Republican governors in Maryland and Massachusetts. If Republicans can’t win by running this white, ethnostate, nostalgia backlash campaigns, then sooner or later they won’t. I think the big question is whether or not, if Donald Trump had lost, I think there would have been this great howling that they hadn’t chosen Marco Rubio or John Casick and instead Hillary Clinton had named the next Supreme Court justice. But because he didn’t lose Trumpism has taken over the party and entrenched itself.

And so, I think one of the big questions, even if you imagine demographic change cutting through some of these divisions and restructuring it so Republicans cannot win, running exactly this strategy is does Republican Party get so captured by it’s base, which does not want to see it diversified, does not want to be told that the future of the Republican Party has to be this more diverse inclusive future, does it get trapped in a sort of almost an innovator’s dilemma situation where it can’t change itself and so has to become like a cornered Wolverine fighting out the rules of American politics? Or do you, at some point do they embrace a more diverse set of standard bearers and try to reform what they are in the way the Democrats did in the late eighties into early nineties and I don’t know the answer to that, but I think that’s one of the interesting questions.

CHRIS HAYES: Yeah.

EZRA KLEIN: That’s why I do think an important thing in American politics, both for the system and just as a value is democracy is good. It’s a good thing and it is good when political parties have to actually appeal to the country as it exists and so both as a value that people should be pushing towards, a rich understanding of democracy, but also as a way to fix a system that has been somewhat deranged by the Republican Party finding that it can maintain this character by choosing a sort of minority rule approach to politics. I think it’s really important to democratize this country and it should be a more central part of the agenda and the discussion.

CHRIS HAYES: Ezra Klein As is the host of the “Ezra Klein Show.” He’s the founder and editor at large of Vox.com. His book, “Why We’re Polarized” is out today. There’s a blurb on the back from yours truly. It is a phenomenal piece of work. It’s sort of the best synthesis of this entire topic that I’ve come across. Ezra, great to have you on.

EZRA KLEIN: Thank you very much, Chris.

CHRIS HAYES: Once again, my great thanks to my friend Ezra Klein. The book is called, “Why we’re Polarized.” It’s out now. You can get it wherever you get your books. I love the book. It’s a really fast read and a really good read. I recommend it. We always love to hear your feedback. You could tweet hashtag with pod, email us [email protected].